Acceleration

About this schools Wikipedia selection

This Schools selection was originally chosen by SOS Children for schools in the developing world without internet access. It is available as a intranet download. A good way to help other children is by sponsoring a child

"Accelerate redirects here. See Accelerate (disambiguation). For the R.E.M. album, see Accelerate (R.E.M. album)

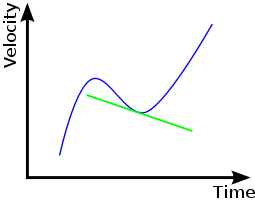

In physics, acceleration is defined as the rate of change of velocity, or as the second derivative of position (with respect to time). It is then a vector quantity with dimension length/time². In SI units, acceleration is measured in meters/second² (m·s-2). The term "acceleration" generally refers to the change in instantaneous velocity.

In common speech, the term acceleration is only used for an increase in speed; a decrease in speed is called deceleration. In physics, any increase or decrease in speed is referred to as acceleration and similarly, motion in a circle at constant speed is also an acceleration, since the direction component of the velocity is changing. See also Newton's Laws of Motion.

Relation to relativity

After completing his theory of special relativity, Albert Einstein realized that forces felt by objects undergoing constant proper acceleration are indistinguishable from those in a gravitational field. This was the basis for his development of general relativity, a relativistic theory of gravity. This is also the basis for the popular Twin paradox, which asks why one twin ages less when moving away from his sibling at near light-speed and then returning, since the non-aging twin can say that it is the other twin that was moving. General relativity solved the "why does only one object feel accelerated?" problem which had plagued philosophers and scientists since Newton's time (and caused Newton to endorse absolute space). In special relativity, only inertial frames of reference (non-accelerated frames) can be used and are equivalent; general relativity considers all frames, even accelerated ones, to be equivalent. (The path from these considerations to the full theory of general relativity is traced in the Introduction to general relativity.)

Formula

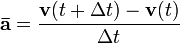

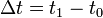

The formula for the average acceleration over a time period  is

is

where

is the final velocity

is the final velocity is the initial velocity

is the initial velocity is the initial time and

is the initial time and  is the change in time

is the change in time

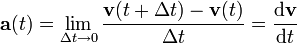

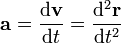

The formula for the instantaneous acceleration at time  is

is

Thus acceleration is the first derivative of velocity. One should note that the expression (Final position - Initial Position) / (Total time taken) is the average velocity, and the limit as the time interval approaches zero is the instantaneous velocity. Therefore, velocity is the first derivative of position, making acceleration the second.

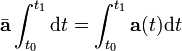

One should also note that the average and instantaneous accelerations over a time period  are related through the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals:

are related through the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals:

Putting it all together means:

where

is acceleration

is acceleration is velocity

is velocity is position

is position is time

is time