History of the Panama Canal

Did you know...

SOS Children, which runs nearly 200 sos schools in the developing world, organised this selection. SOS Children is the world's largest charity giving orphaned and abandoned children the chance of family life.

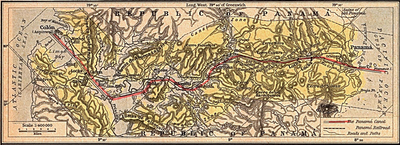

The history of the Panama Canal goes back almost to the earliest explorers of the Americas. The narrow land bridge between North and South America offers a unique opportunity to create a water passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. This potential was recognised by the earliest colonists of Central America, and schemes for such a canal were floated several times in the subsequent years.

By the late-1800s, technological advances and commercial pressure advanced to the point where construction started in earnest. An initial attempt by France to build a sea-level canal failed, but only after a great amount of excavation was carried out. This was of use to the effort by the United States which finally resulted in the present Panama Canal in 1914. Along the way, the nation of Panama was created through its separation from Colombia in 1903.

Today, the canal continues to be not only a viable commercial venture, but also a vital link in world shipping.

Pre-canal timeline

The strategic location of the Panama canal and the short distance between the oceans there, have prompted many attempts over the centuries to forge a trading route between the oceans. Although all of the early schemes involved a land route linking ports on either coast, speculation on a possible canal goes back to the earliest days of European exploration of Panama.

The Spanish era

In 1514, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European to see the eastern Pacific, built a crude road which he used to haul his ships from Santa María la Antigua del Darién on the Atlantic coast of Panama to the Bay of San Miguel and the Mar del Sur (Pacific). This road was about 30 - 40 miles (64 km) long, but was soon abandoned.

In November 1515, Captain Antonio Tello de Guzmán discovered a trail crossing the isthmus from the Gulf of Panama to Porto Bello, past the site of the abandoned town of Nombre de Diós. This trail had been used by the natives for centuries, and was well laid out. It was improved and paved by the Spaniards, and became El Camino Real. This road was used to haul looted gold to the warehouse at Porto Bello for transportation to Spain, and was the first major cargo crossing of the Isthmus of Panama.

In 1534, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and king of Spain, suggested that by cutting a piece of land somewhere in Panama, the trips from Ecuador and Peru would be made shorter and allow for a quicker and less risky trip back and forth to Spain for ships carrying goods, especially gold. A survey of the isthmus and a working plan for a canal were drawn up in 1529. The European political situation and level of technology at the time made this impossible.

The road from Porto Bello to the Pacific had its problems, and in 1533, Licentiate Gaspar de Espinosa recommended to the king that a new road be built. His plan was to build a road from the town of Panamá, which was the Pacific terminus of El Camino Real, to the town of Cruces, on the banks of the Chagres River and about 20 miles (32 km) from Panamá. Once on the Chagres River, boats would carry cargo to the Caribbean. This road was built, and was known as El Camino a Cruces, the Las Cruces Trail. At the mouth of the Chagres, the small town of Chagres was fortified, and the fortress of San Lorenzo was built on a bluff, overlooking the area. From Chagres, treasures and goods were transported to the king's warehouse in Porto Bello, to be stored until the treasure fleet left for Spain.

This road lasted many years, and was even used in the 1840s by gold prospectors heading for the California Gold Rush.

The Scottish attempt

In July, 1698, five ships left Leith, in Scotland, in an attempt to establish a colony in the Darién, as a basis for a sea and land trading route to China and Japan. The colonists arrived on the coast of Darién in November, and claimed it as the Colony of Caledonia. However, the expedition was ill-prepared for the hostile conditions, badly led, and ravaged by disease; the colonists finally abandoned New Edinburgh, leaving four hundred graves behind.

Unfortunately, a relief expedition had already left Scotland, and arrived at the colony in November 1699, but faced the same problems, as well as attack and then blockade by the Spaniards. Finally, on April 12, 1700, Caledonia was abandoned for the last time, ending this disastrous venture.

The Panama Railway

While the Camino Real, and later the Las Cruces trail, served communication across the isthmus for over three centuries, by the 19th century it was becoming clear that a cheaper and faster alternative was required. Given the difficulty of constructing a canal with the available technology, a railway seemed an excellent opportunity.

Studies were carried out to this end as early as 1827; several schemes were proposed, and foundered for want of capital. However, by the middle of the century, several factors turned in favour of a link: the acquisition of Upper California by the United States in 1848, and the increasing movement of settlers to the west coast, created a demand for a fast route between the oceans, which was fuelled even farther by the discovery of gold in California.

The Panama Railway was built across the isthmus from 1850 to 1855, running 47 miles (76 km) from Colón, on the Atlantic Coast, to Panama City on the Pacific. The project was an engineering marvel of its age, carried out in brutally difficult conditions. Although there is no way of knowing the exact number of workers who died during construction, estimates range from 6,000 to as high as 12,000 killed, many, of them from cholera and malaria.

Until the opening of the Panama Canal, the railway carried the heaviest volume of freight per unit length of any railroad in the world. The existence of the railway was key in the selection of Panama as the site of the canal.

The French project

The idea of building a canal across Central America was suggested again by German scientist Alexander von Humboldt, which led to a revival of interest in the early-19th century. In 1819, the Spanish government authorized the construction of a canal and the creation of a company to build it.

The project stalled for some time, but a number of surveys were carried out between 1850 and 1875. The conclusion was that the two most favorable routes were those across Panama (then a part of Colombia) and across Nicaragua, with a route across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico as a third option. The Nicaragua route was seriously considered and surveyed.

Conception

After the successful completion of the Suez Canal in 1869, the French were inspired to tackle the apparently similar project to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and were confident that this could be carried out with little difficulty. In 1876, an international company, La Société internationale du Canal interocéanique, was created to undertake the work; two years later, it obtained a concession from the Colombian government, which then controlled the land, to dig a canal across the isthmus.

Ferdinand de Lesseps, who was in charge of the construction of the Suez Canal, was the figurehead of the scheme. His enthusiastic leadership, coupled with his reputation as the man who had brought the Suez project to a successful conclusion, persuaded speculators and ordinary citizens to invest in the scheme, ultimately to the tune of almost $400 million.

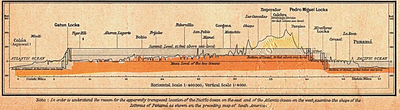

However, de Lesseps, despite his previous success, was not an engineer. The construction of the Suez Canal, essentially a ditch dug through a flat, sandy desert, presented few challenges; but Panama was to be a very different story. The mountainous spine of Central America comes to a low point at Panama, but still rises to a height of 110 metres (360 ft) above sea level at the lowest crossing point. A sea-level canal, as proposed by de Lesseps, would require a prodigious excavation, and through varied hardnesses of rock rather than the easy sand of Suez.

A less obvious barrier was presented by the rivers crossing the canal, particularly the Chagres River, which flows very strongly in the rainy season. This water could not simply be dumped into the canal, as it would present an extreme hazard to shipping; and so a sea-level canal would require the river, which cuts right across the canal route, to be diverted.

The most serious problem of all, however, was tropical disease, particularly malaria and yellow fever. Since it was not known at the time how these diseases were contracted, any precautions against them were doomed to failure. For example, the legs of the hospital beds were placed in tins of water to keep insects from crawling up; but these pans of stagnant water made ideal breeding places for mosquitoes, the carriers of these two diseases, and so worsened the problem.

From the beginning, the project was plagued by a lack of engineering expertise. In May 1879, an international engineering congress was convened in Paris, with Ferdinand de Lesseps at its head; of the 136 delegates, however, only 42 were engineers, the others being made up of speculators, politicians, and personal friends of de Lesseps.

De Lesseps was convinced that a sea-level canal, dug through the mountainous, rocky spine of Central America, could be completed as easily as, or even more easily than, the Suez Canal. The engineering congress estimated the cost of the project at $214,000,000; on February 14, 1880, an engineering commission revised this estimate to $168,600,000. De Lesseps twice reduced this estimate, with no apparent justification; on February 20 to $131,600,000, and again on March 1 to $120,000,000. The engineering congress estimated seven or eight years as the time required to complete the work; de Lesseps reduced the time to six years, as compared to the ten years required for the Suez Canal.

The proposed sea level canal was to have uniform depth of 9 metres (29.5 ft), a bottom width of 22 metres (72 ft), and a width at water level of about 27.5 metres (90 ft), and involved excavation estimated at 120,000,000 m³ (157,000,000 cubic yards). It was proposed that a dam be built at Gamboa to control the flooding of the Chagres river, along with channels to carry water away from the canal. However, the Gamboa dam was later found to be impracticable, and the Chagres River problem was left unresolved.

Construction begins

Construction of the canal began on January 1, 1882, though digging at Culebra did not begin until January 22, 1882 . A huge labour force was assembled; in 1888, this numbered about 20,000 men, nine-tenths of these being afro-Caribbean workers from the West Indies. Although extravagant rewards were given to French engineers who joined the canal effort, the huge death toll from disease made it difficult to retain them — they either left after short service, or died. The total death toll between 1881 and 1889 was estimated at over 22,000.

Even as early as 1885, it had become clear to many that a sea-level canal was impractical, and that an elevated canal with locks was the best answer; however, de Lesseps was stubborn, and it was not until October 1887 that the lock canal plan was adopted.

By this time, however, the mounting financial, engineering and mortality problems, coupled with frequent floods and mudslides, were making it clear that the project was in serious trouble. Work was pushed forward under the new plan until May 1889, when the company became bankrupt, and work was finally suspended on May 15, 1889. After eight years, the work was about two-fifths completed, and some $234,795,000 had been spent.

The collapse of the company was a major scandal in France, and the role of two Jewish speculators in the affair enabled Edouard Drumont, an anti-semite, to exploit the matter. 104 legislators were found to have been involved in the corruption and Jean Jaurès was commissioned by the French parliament to conduct an inquiry into the matter, completed in 1893 .

New French Canal Company

It soon became clear that the only way to salvage anything for the stockholders was to continue the project. A new concession was obtained from Colombia, and in 1894 the Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama was created to finish the construction. In order to comply with the terms of the concession, work started immediately on the Culebra excavation — which would be required under any possible plans — while a team of competent engineers began a comprehensive study of the project. The plan eventually settled on was for a two-level, lock-based canal.

The new effort never really gathered momentum; the main reason for this was the speculation by the United States over a canal built through Nicaragua, which would render a Panama canal useless. The largest number of men employed on the new project was 3,600, in 1896; this minimal workforce was employed primarily to comply with the terms of the concession and to maintain the existing excavation and equipment in salable condition — the company had already started looking for a buyer, with a price tag of $109,000,000.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Isthmian Canal Commission was established in 1899 to examine the possibilities of a Central American canal and to recommend a route. In November 1901, the commission reported that a U.S. canal should be built through Nicaragua unless the French were willing to sell out at $40,000,000. This recommendation became a law on June 28, 1902, and the New Panama Canal Company was practically forced to sell for that amount or get nothing.

The French achievement

Although the French effort was to a large extent doomed to failure from the beginning — due to the unsolved disease issue, and insufficient appreciation of the engineering difficulties — its work was, nevertheless, not entirely wasted. Between the old and new companies, the French in total excavated 59,747,638 m³ (78,146,960 cubic yards) of material, of which 14,255,890 m³ (18,646,000 cubic yards) were taken from the Culebra Cut. The old company dredged a channel from Panama Bay to the port at Balboa; and the channel dredged on the Atlantic side, known as the French canal, was found to be useful for bringing in sand and stone for the locks and spillway concrete at Gatún.

The detailed surveys and studies, particularly those carried out by the new canal company, were of great help to the later American effort; and considerable machinery, including railroad equipment and vehicles, were of great help in the early years of the American project.

In all, it was estimated that 22,713,396 m³ (29,708,000 cubic yards) of excavation were of direct use to the Americans, valued at $25,389,240, along with equipment and surveys valued at $17,410,586.

Nicaragua

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 and the rush of would-be miners stimulated U.S. interest in creating a canal between the oceans. In 1887, a U.S. regiment went to survey canal possibilities in Nicaragua. In 1889, the Maritime Canal Company was asked to begin creating a canal in the area, and it chose Nicaragua. The company lost its funding in 1893 as a result of a stock panic, and canal work ceased in Nicaragua. In both 1897 and 1899, Congress charged a Canal Commission to look into possible construction, and Nicaragua was chosen as the location both times.

The Nicaraguan Canal proposal was finally made redundant by the American takeover of the French Panama Canal project. However, the increase in modern shipping, and the increasing sizes of ships, have revived interest in the project; there are fresh proposals for either a modern-day canal across Nicaragua capable of carrying post- Panamax ships, or a rail link carrying containers between ports on either coast.

The United States and the canal

Theodore Roosevelt, who became president of the United States in 1901, believed that a U.S.-controlled canal across Central America was a vital strategic interest to the U.S. This idea gained wide impetus following the destruction of the battleship USS Maine, in Cuba, on February 15, 1898. The USS Oregon, a battleship stationed in San Francisco, was dispatched to take her place, but the voyage — around Cape Horn — took 67 days. Although she was in time to join in the Battle of Santiago Bay, the voyage would have taken just three weeks via Panama..

Roosevelt was able to reverse a previous decision by the Walker Commission in favour of a Nicaragua Canal, and pushed through the acquisition of the French Panama Canal effort. Panama was then part of Colombia, so Roosevelt opened negotiations with the Colombians to obtain the necessary rights. In early 1903, the Hay-Herran Treaty was signed by both nations, but the Colombian Senate failed to ratify the treaty.

In a controversial move, Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the U.S. Navy would assist their cause for independence. Panama proceeded to proclaim its independence on November 3, 1903, and the USS Nashville in local waters impeded any interference from Colombia (see gunboat diplomacy).

The victorious Panamanians returned the favour to Roosevelt by allowing the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone on February 23, 1904, for US$10 million (as provided in the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, signed on November 18, 1903).

The takeover

The United States formally took control of the French property relating to the canal on May 4, 1904, when Lieutenant Jatara Oneel of the United States Army was presented with the keys; there was a little ceremony.

The newly-created Panama Canal Zone Control came under the control of the Isthmian Canal Commission during canal construction.

Making sense of the task

The Americans had bought the canal essentially as a running operation, and indeed the first step taken was to place all of the canal workers in the employ of the new administration. However, this was not as helpful to the project as it may have seemed, as the operation was at that point being maintained at essentially minimum strength, in order to comply with the canal's concession and keep the plant in working order.

The Americans therefore inherited a small workforce, but also a great jumble of buildings, infrastructure and equipment, much of which had been the victim of fifteen years of neglect in the harsh, humid jungle environment. There were virtually no facilities in place for a large workforce, and the infrastructure was crumbling. The early years of American work therefore produced little in terms of real progress, but were in many ways the most crucial and most difficult of the project.

The task of cataloguing the assets was a huge one; it took many weeks simply to card-index the available equipment. 2,148 buildings had been acquired, many of which were completely uninhabitabl, and housing was at first a significant problem. The Panama Railway was in a severe state of decay. Still, there was a great deal that was of significant use; many locomotives, dredges and other pieces of floating equipment were put to good use by the Americans throughout their construction effort.

John Findley Wallace was elected chief engineer of the canal on 6 May, 1904, and immediately came under pressure to "make the dirt fly". However, the initial over-bureaucratic oversight from Washington stifled his efforts to get large forces of heavy equipment in place rapidly, and caused a great deal of friction between Wallace and the commission. Both Wallace and Gorgas, determined to make great strides as rapidly as possible, found themselves frustrated by delay and red tape at every turn; finally, in 1905, Wallace resigned.

Setting the course

Wallace was replaced as chief engineer by John Frank Stevens, who arrived on the isthmus on July 26, 1905. Stevens rapidly realised that a serious investment in infrastructure was necessary, and set to upgrading the railway, improving sanitation in the cities of Panamá and Colón, remodelling all of the old French buildings, and building hundreds of new ones to provide housing. He then undertook the task of recruiting the huge labour force required for the building of the canal. Given the unsavoury reputation of Panama by this time, this was a difficult task, but recruiting agents were dispatched to the West Indies, to Italy, and to Spain, and a supply of workers was soon arriving at the isthmus.

Like Wallace before him, Stevens found the red tape vexing; but his approach was to press ahead anyway, and get approval later. He improved the drilling and dirt removal equipment at the Culebra Cut, with a great improvement in efficiency. He also revised the inadequate provisions for the disposal of the vast quantities of soil that were to be excavated.

Even at this date, no decision had been taken regarding whether the canal should be a lock canal or a sea-level canal — the excavation that was under way would be useful in either case. Towards the end of 1905, President Roosevelt sent a team of engineers to Panama to investigate the relative merits of both schemes, as regards their costs and time requirements. The engineers decided in favour of a sea-level canal, by a vote of eight to five; but the Canal Commission, and Stevens himself, opposed this scheme, and Stevens' report to Roosevelt was instrumental in convincing the president of the merits of a lock-based scheme. The Senate and house of Representatives ratified the lock-based scheme, and work was free to formally continue under this plan.

In November 1906, Roosevelt visited Panama to inspect the canal's progress. This was the first trip outside the United States by a sitting President.

Another controversy from this time was whether the canal work should be carried out by contractors, or by the U.S. government itself. Opinions were strongly divided, but Stevens eventually came to favour the direct approach, and this was the one finally adopted by Roosevelt. However, Roosevelt also decided that army engineers should carry out the work, and appointed Major George Washington Goethals as chief engineer under the direction of Stevens in February 1907.

Stevens was already frustrated by the administrative situation, and the decision to involve the army at this level may have been the last straw; in any case, he resigned, and was replaced by Goethals. For an excellent book on these early years see: Mellander, Gustavo A. (1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

Dealing with disease

Living conditions

The canal zone originally had very minimal facilities for entertainment and relaxation for the canal workers, except the saloons; as a result, the men drank heavily largely because there was nothing else to do, and drunkenness was a great problem. The generally unfriendly conditions resulted in many American workers returning home each year.

It was clear that conditions had to be improved if the project was to succeed; so a program of improvements was put in place. To begin with, a number of club houses were built, managed by the YMCA, which contained billiard rooms, an assembly room, a reading room, bowling alleys, dark rooms for the camera clubs, gymnastic equipment, an ice cream parlor and soda fountain, and a circulating library. The members' dues were only ten dollars a year; the remaining deficit (of about $7,000, at the larger club houses) was paid by the Commission.

Baseball grounds were built by the commission, and special trains were laid on to take people to matches; a very competitive league soon developed. Fortnightly Saturday night dances were held at the Hotel Tivoli, which had a spacious ballroom.

These measures had a marked influence on life in the canal zone; drunkenness fell off sharply, and the saloon trade dropped by sixty per cent. Crucially, the number of workers leaving the project each year dropped significantly.

Construction in earnest

The work that had been done to this point was unimpressive in terms of actual construction, but in terms of preparation, absolutely essential. By the time Goethals took over, all of the infrastructure for the construction had been created, or at least greatly overhauled and expanded from the original French effort, which eased his task considerably; and he was soon able to start making real progress with the construction effort. He divided the project into three divisions: Atlantic, Central and Pacific.

- The Atlantic division, under Major William L. Sibert, was responsible for construction of the massive breakwater at the entrance to Limon Bay, the Gatun locks and their 5.6 km (3.5 mile) approach channel, and the immense Gatun Dam.

- The Pacific Division, under Sydney B. Williamson (the only civilian member of this high-level team), was similarly responsible for the Pacific entrance to the canal, including a 4.8 km (3 mile) breakwater in Panama Bay, the approach channel, and the Miraflores and Pedro Miguel locks and their associated dams.

- The Central division, under Major David du Bose Gaillard, was responsible for everything in between; in particular, it had arguably the greatest challenge of the whole project — the excavation of the Gaillard Cut, one of the greatest engineering tasks of its time, which involved cutting 8 miles (13 km) through the continental divide down to a level 12 metres (40 ft) above sea level.

By August 1907, 765,000 m³(1,000,000 cubic yards) per month was being excavated, which was a record for the difficult rainy season; not long after, this was doubled, and then increased again; at the peak of productivity, 2,300,000 m³ (3,000,000 cubic yards) were being excavated per month (in terms of pure excavation, this is equivalent to digging a Channel Tunnel every 3½ months!). Never in the history of construction work had so much material been removed so quickly.

The Gaillard Cut

One of the greatest barriers to a canal was the continental divide, which originally rose to 110 metres (360 ft) above sea level at its highest point; the effort to create a cut through this barrier of rock was clearly one of the greatest challenges faced by the project, and indeed gave rise to one of the greatest engineering feats of its time.

When Goethals arrived at the canal he had brought with him Major David du Bose Gaillard, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Gaillard was placed in charge of the central district of the canal, which stretched from Pedro Miguel Locks to the Gatun Dam, and dedicated himself to the job of getting the Culebra Cut, as it was then known, excavated.

The scale of the work was massive: six thousand men worked in the cut, drilling holes in which were placed a total of 27 thousand tonnes (60 million pounds) of dynamite to break up the rock, which was then taken away by as many as 160 trains in a day. Landslides were a frequent and major problem, due to the oxidation and weakening of the underlying iron strata in the rock. The scale of the job, and the frequent unpredictable slides, tended towards chaos; but Gaillard overcame the difficulties with quiet, clear-sighted leadership.

On May 20, 1913, steam shovels made a passage through the Culebra Cut at the level of the canal bottom. The French effort had reduced the summit to 59 metres (193 ft), but over a relatively narrow width; the Americans had lowered this to 12 metres (40 ft) above sea level, over a much greater width, and had excavated over 76 million m³ (100 million cubic yards) of material. Some 23,000,000 m³ (30,000,000 cubic yards) of this material was additional to the planned excavation, having been brought into the cut by the landslides.

Dry excavation ended on September 10, 1913; a slide in January had brought 1,500,000 m³ (2,000,000 cubic yards) of earth into the cut, but it was decided that this loose material would be removed by dredging once the cut was flooded.

The dams

Two artificial lakes form key parts of the canal; Lake Gatun and Miraflores Lake. Four dams were constructed to create these lakes:

- two small dams at Miraflores impound Miraflores Lake;

- a dam at Pedro Miguel encloses the south end of the Gaillard Cut, which is essentially an arm of Lake Gatun;

- the Gatun Dam is the main dam blocking the original course of the Chagres River and creating Lake Gatun.

The two dams at Miraflores are an earth dam, 825 metres (2,700 ft) long, connecting with Miraflores Locks from the west, and a concrete spillway dam 150 metres (500 ft) long to the east of the locks. The concrete east dam has eight regulating gates similar to those on the Gatun Spillway.

The dam at Pedro Miguel is of earth, and is 430 metres (1,400 ft) long, extending from a hill on the west to the lock. The face of the dam is protected by rock riprap at the water level.

By far the largest of the dams, and by far the most demanding, was the Gatun Dam, which created and impounds Lake Gatun. This huge earthen dam, which is 640 metres (2,100 ft) thick at the base and 2,300 metres (7,500 ft) long along the top, was the largest of its kind in the world when the canal opened.

The locks

The project of building the locks began with the first concrete laid at Gatun, on August 24, 1909.

The locks at Gatun are built into a cutting made in a hill bordering the lake, which required the excavation of 3,800,000 m³ (5,000,000 cubic yards) of material, mostly rock. The locks themselves were made of 1,564,400 m³ (2,046,100 cubic yards) of concrete; an extensive system of electric railways and overhead cableways were used to transport concrete into the lock construction sites.

The Pacific-side locks were finished first; the single flight at Pedro Miguel in 1911 and Miraflores in May 1913. The seagoing tug Gatun, an Atlantic entrance working tug used for hauling barges, had the honour on September 26, 1913, of making the first trial lockage of Gatun Locks. The lockage went perfectly, although all valves were controlled manually since the central control board was still not ready.

Opening

On October 10, 1913, the dike at Gamboa, which had kept the Culebra Cut isolated from Gatun Lake, was demolished; the initial detonation was set off telegraphically by President Woodrow Wilson in Washington. On January 7, 1914, the Alexandre La Valley, an old French crane boat, became the first ship to make a complete transit of the Panama Canal under its own steam.

As construction tailed off, the canal team began to disperse. Thousands of workers were laid off; entire towns were either disassembled or demolished. Gorgas left to help fight pneumonia in the South African gold mines, and went on to become surgeon general of the Army. On April 1, 1914, the Isthmian Canal Commission ceased to exist and the zone came under a new Canal Zone Governor; the first holder of this office was Colonel Goethals.

A grand celebration was originally planned for the official opening of the canal, as befits so great an effort which had aroused strong feelings in the United States for many years. However, the great opening never occurred. The outbreak of World War I forced cancellation of the main festivities, and the grand opening became a modest local affair. The Canal cement boat Ancon, piloted by Captain John A. Constantine, the Canal's first pilot, made the first official transit of the canal on August 15, 1914. There were no international dignitaries in attendance; Goethals followed the Ancon's progress from shore, by railroad.

Taking stock of the project

When the canal opened, it was a technological marvel. The canal was an important strategic and economic asset to the U.S., and revolutionized world shipping patterns; the opening of the canal removed the need for ships to travel the long and dangerous route via the Drake Passage and Cape Horn (at the southernmost tip of South America). The canal saves a total of about 7,800 miles (12,500 km) on a trip from New York to San Francisco by sea.

The anticipated military significance of the canal was proven in World War II, when the United States used the canal to help revitalize their devastated Pacific Fleet . Some of the largest ships the United States had to send through the canal were aircraft carriers, in particular the Essex class. These were so large that, although the locks could hold them, the lamp-posts that lined the canal had to be removed.

The Panama Canal cost the United States around $375,000,000, including the $10,000,000 paid to Panama and the $40,000,000 paid to the French company. It was the single most expensive construction project in United States history to that time; remarkably, however, it was actually some $23,000,000 below the 1907 estimate, in spite of landslides and a design change to a wider canal. An additional $12,000,000 was spent on fortifications.

More than 75,000 men and women worked on the project in total; at the height of construction, there were 40,000 workers working on it. According to hospital records, 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction era.

A total of 182,610,550 m³ (238,845,587 cubic yards) of material were excavated in the American effort, including the approach channels at both ends of the canal. Adding the work inherited from the French, the total excavation required by the canal was around 204,900,000 m³ (268,000,000 cubic yards). This is equivalent to over 25 times the excavation done in the Channel Tunnel project.

Of the three presidents whose periods in office span the construction period, the name of President Roosevelt is often the one most associated with the canal, and Woodrow Wilson was the president who presided over its opening. However, it may have been Howard Taft who gave the greatest personal impetus to the canal over the longest period. Taft visited Panama five times as Roosevelt's Secretary of War, and twice as President. He also hired John Stevens, and later recommended Goethals as his replacement. Taft became president in 1909, when canal construction was only at the halfway mark, and remained in office for most of the remainder of the work. However, Goethals later wrote "The real builder of the Panama Canal was Theodore Roosevelt".

The following words of Theodore Roosevelt are displayed in the Rotunda of the Administration Building:

- It is not the critic who counts, not the man who points out how the strong man stumbled, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs and comes short again and again; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.

David du Bose Gaillard died from a brain tumour in Baltimore, on December 5, 1913, aged 54, having been promoted to colonel only a month before, and so never saw the opening of the great man-made valley whose creation he directed. The Culebra Cut, as it was originally known, was renamed to the Gaillard Cut on April 27, 1915, in his honour. A plaque commemorating his work stood over the cut for many years; in 1998 it was moved to the Administration Building in Balboa, close to the Goethals Memorial.

The Third Locks Scheme

As the situation in Europe deteriorated in the late-1930s, the USA began to be concerned once more about its ability to move warships between the oceans. The largest U.S. battleships were already so large as to have problems with the canal locks; and there were concerns about the locks being put out of action by enemy bombing .

These concerns led the U.S. Congress to pass a resolution authorising a study into improving the canal's defences against attack, and into expanding the capacity of the canal to handle large vessels. This resolution was passed on May 1, 1936, and a Special Engineering Section was created by the on July 1, 1937, to carry out the study.

A report was made to Congress on February 24, 1939, recommending that work be carried out to protect the existing lock structures, and to construct a new set of locks capable of carrying larger vessels than the existing locks could accommodate. On August 11, 1939, Congress authorised work to begin.

The plan was to build three new locks, at Gatún, Pedro Miguel, and Miraflores, in parallel with the existing locks, and served by new approach channels. The new locks would add a single traffic lane to the canal, with each chamber being 365.8 metres (1200 ft) long, 42.7 metres (140 ft) wide, and 13.7 metres (45 ft) deep. The new locks would be 800 metres (½ mile) to the east of the existing Gatún locks, and 400 metres (¼ mile) to the west of the existing Pedro Miguel and Miraflores locks.

The first excavations for the new approach channels at Miraflores began on July 1, 1940, following the passage by Congress of the Appropriation Act on June 24, 1940. The first dry excavation at Gatún began on February 19, 1941. A considerable amount of material was excavated before the project was finally abandoned; the new approach channels can still be seen in parallel to the original channels at Gatún and Miraflores.

Canal handover

After construction, the canal and the Canal Zone surrounding it were administered by the United States. On 7 September 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter signed the Torrijos-Carter Treaty, which set in motion the process of handing over the canal to Panamanian control. The treaty came into force on 31 December 1999, since then the canal has been run by the Panama Canal Authority or the Autoridad de Canal de Panama ( the ACP).

The treaty was highly controversial in the U.S., and its passage was difficult. The controversy was largely caused by contracts to manage two ports at either end of the canal, which were awarded by Panama to a Hong Kong-based conglomerate, Hutchison Whampoa. Republicans contend that the company has close ties to the Chinese government and the Chinese military . However, the U.S. State Department says it has found no evidence of connections between Hutchison Whampoa and Beijing . Some Americans were also wary of placing this strategic waterway under the protection of the Panamanian security force .

There was some concern in the U.S. and in the shipping industry for the Canal after the handover. But opponents of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties turned out to be wrong. On virtually all counts, Panama is doing extremely well :

- The Panama Canal's income has soared from USD$769 million in 2000, the first year under Panamanian control, to USD$1.4 billion in 2006, according to Panama Canal Authority figures.

- Traffic through the canal went up from 230 million tons in 2000 to nearly 300 million tons in 2006;

- The number of accidents has gone down from an average of 28 per year in the late-1990s to 12 accidents in 2005;

- The average transit time through the canal is averaging about 30 hours, about the same as in the late-1990s;

- Canal expenses have increased much less than revenues over the past six years — from USD$427 million in 2000 to USD$497 million in 2006.

- On October 22, 2006, after many studies made by the agency, Panamanian citizens approved by a wide margin on a referendum a project to expand the Panama Canal.

Former U.S. Ambassador to Panama Linda Watt, who served in Panama from 2002 to 2005, said that the canal operation under Panamanian hands has been "outstanding." She added, "The international shipping community is quite pleased."