1993 Russian constitutional crisis

Background to the schools Wikipedia

The articles in this Schools selection have been arranged by curriculum topic thanks to SOS Children volunteers. SOS Children works in 45 African countries; can you help a child in Africa?

| 1993 Russian constitutional crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tanks of the Taman Division shooting at the Russian White House. October 4, 1993. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alexander Korzhakov Pavel Grachev Viktor Yerin Anatoly Kulikov |

Ruslan Khasbulatov Albert Makashov Alexander Barkashov |

||||||

| ^ Declared himself Acting President of the Russian Federation | |||||||

The Russian constitutional crisis of 1993 was a political stand-off between the Russian president and the Russian parliament that was resolved by using military force. The relations between the president and the parliament had been deteriorating for a while. They reached a tipping point on September 21, when Russian president Boris Yeltsin dissolved the country's legislature ( Congress of People's Deputies and its Supreme Soviet). The president did not have the power to dissolve the parliament according to the then-current constitution. Yeltsin used the results of the referendum of April 1993 to justify his actions. In response, the parliament impeached Yeltsin and proclaimed vice president Aleksandr Rutskoy acting president.

The situation deteriorated at the beginning of October. On Sunday, October 3, demonstrators removed police cordons around the parliament and, urged by their leaders, took over the Mayor's offices and tried to storm the Ostankino television centre. The army, which had initially declared its neutrality, by Yeltsin's orders stormed the Supreme Soviet building in the early morning hours of October 4, and arrested the leaders of the resistance.

The ten-day conflict had seen the deadliest street fighting in Moscow since October 1917. According to government estimates, 187 people were killed and 437 wounded, while sources close to Russian communists put the death toll at as high as 2,000.

Origins of the crisis

The intensifying executive-legislative power struggle

Yeltsin's economic reform program took effect on January 2, 1992.. Soon afterward prices skyrocketed, government spending was slashed, and heavy new taxes went into effect. A deep credit crunch shut down many industries and brought about a protracted depression. Certain politicians began quickly to distance themselves from the program; and increasingly the ensuing political confrontation between Yeltsin on the one side, and the opposition to radical economic reform on the other, became centered in the two branches of government.

Real GDP percentage change in Russia, 1990-1994.

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -3.0% | -13.0% | -19.0% | -12.0% | -15.0% |

Throughout 1992, opposition to Yeltsin's reform policies grew stronger and more intractable among bureaucrats concerned about the condition of Russian industry and among regional leaders who wanted more independence from Moscow. Russia's vice president, Aleksandr Rutskoy, denounced the Yeltsin program as "economic genocide." Indeed, during the first half of the year 1992, the average income of the population declined 2-2.5 times. Leaders of oil-rich republics such as Tatarstan and Bashkiria called for full independence from Russia.

Also throughout 1992, Yeltsin wrestled with the Supreme Soviet (the standing legislature) and the Russian Congress of People's Deputies (the country's highest legislative body, from which the Supreme Soviet members were drawn) for control over government and government policy. In 1992 the speaker of the Russian Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov, came out in opposition to the reforms, despite claiming to support Yeltsin's overall goals.

The president was concerned about the terms of the constitutional amendments passed in late 1991, which meant that his special powers of decree were set to expire by the end of 1992 (Yeltsin expanded the powers of the presidency beyond normal constitutional limits in carrying out the reform program). Yeltsin, awaiting implementation of his privatization program, demanded that parliament reinstate his decree powers (only parliament had the authority to replace or amend the constitution). But in the Russian Congress of People's Deputies and in the Supreme Soviet, the deputies refused to adopt a new constitution that would enshrine the scope of presidential powers demanded by Yeltsin into law.

The seventh Congress of People's Deputies

During its December session the parliament clashed with Yeltsin on a number of issues, and the conflict came to a head on December 9 when the parliament refused to confirm Yegor Gaidar, the widely unpopular architect of Russia's " shock therapy" market liberalizations, as prime minister. The parliament refused to nominate Gaidar, demanding modifications of the economic program and directed the Central Bank, which was under the parliament's control, to continue issuing credits to enterprises to keep them from shutting down.

In an angry speech the next day on December 10, Yeltsin accused the Congress of blocking the government's reforms and suggested the people decide on a referendum, "which course do the citizens of Russia support? The course of the President, a course of transformations, or the course of the Congress, the Supreme Soviet and its Chairman, a course towards folding up reforms, and ultimately towards the deepening of the crisis." Parliament responded by voting to take control of the parliamentary army.

On December 12, Yeltsin and parliament speaker Khasbulatov agreed on a compromise that included the following provisions: (1) a national referendum on framing a new Russian constitution to be held in April 1993; (2) most of Yeltsin's emergency powers were extended until the referendum; (3) the parliament asserted its right to nominate and vote on its own choices for prime minister; and (4) the parliament asserted its right to reject the president's choices to head the Defense, Foreign Affairs, Interior, and Security ministries. Yeltsin nominated Viktor Chernomyrdin to be prime minister on December 14, and the parliament confirmed him.

Yeltsin's December 1992 compromise with the seventh Congress of the People's Deputies temporarily backfired. Early 1993 saw increasing tension between Yeltsin and the parliament over the language of the referendum and power sharing. In a series of collisions over policy, the congress whittled away the president's extraordinary powers, which it had granted him in late 1991. The legislature, marshaled by Speaker Ruslan Khasbulatov, began to sense that it could block and even defeat the president. The tactic that it adopted was gradually to erode presidential control over the government. In response, the president called a referendum on a constitution for April 11.

The eighth congress

The eighth Congress of People's Deputies opened on March 10, 1993 with a strong attack on the president by Khasbulatov, who accused Yeltsin of acting unconstitutionally. In mid-March, an emergency session of the Congress of People's Deputies voted to amend the constitution, strip Yeltsin of many of his powers, and cancel the scheduled April referendum, again opening the door to legislation that would shift the balance of power away from the president. The president stalked out of the congress. Vladimir Shumeyko, first deputy prime minister, declared that the referendum would go ahead, but on April 25.

The parliament was gradually expanding its influence over the government. On March 16 the president signed a decree that conferred Cabinet rank on Viktor Gerashchenko, chairman of the central bank, and three other officials; this was in accordance with the decision of the eighth congress that these officials should be members of the government. The congress' ruling, however, had made it clear that as ministers they would continue to be subordinate to parliament. In general, the parliament's lawmaking activity decreased in 1993, as its agenda increasingly became to be dominated by efforts to increase the parliamentarian powers and reduce those of the president.

The "special regime"

The president's response was dramatic. On March 20, Yeltsin addressed the nation directly on television, declaring that he had signed a decree on a "special regime" (“Об особом порядке управления до преодоления кризиса власти″), under which he would assume extraordinary executive power pending the results of a referendum on the timing of new legislative elections, on a new constitution, and on public confidence in the president and vice-president. Yeltsin also bitterly attacked the parliament, accusing the deputies of trying to restore the Soviet-era order.

Soon after Yeltsin's televised address, Valery Zorkin (Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation), Yuri Voronin (first vice-chairman of the Supreme Soviet), Alexander Rutskoy and Valentin Stepankov ( Prosecutor General) made an address, publicly condemning Yeltsin's declaration as unconstitutional. On March 23, though not yet possessing the signed document, the Constitutional Court ruled that some of the measures proposed in Yeltsin's TV address were unconstitutional. However, the decree itself, that was only published a few days later, did not contain unconstitutional steps.

The ninth congress

The ninth congress, which opened on March 26, began with an extraordinary session of the Congress of People's Deputies taking up discussions of emergency measures to defend the constitution, including impeachment of President Yeltsin. Yeltsin conceded that he had made mistakes and reached out to swing voters in parliament. Yeltsin narrowly survived an impeachment vote on March 28, votes for impeachment falling 72 short of the 689 votes needed for a 2/3 majority. The similar proposal to dismiss Ruslan Khasbulatov, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet was defeated by a wider margin (339 in favour of the motion), though 614 deputies had initially been in favour of including the re-election of the chairman in the agenda, a tell-tale sign of the weakness of Khasbulatov's own positions (517 votes for would have sufficed to dismiss the speaker).

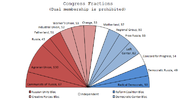

By the time of the ninth Congress, the legislative branch was dominated by the Russian Unity bloc, which included representatives of the CPRF and the Fatherland faction (communists, retired military personnel, and other deputies of a socialist orientation), Agrarian Union, and the faction " Russia" led by Sergey Baburin. Together with more 'centrist' groups (e.g. 'Change' (Смена)), the Yeltsin supporters ('Democratic Russia', 'Radical democrats') were clearly left in the minority.

National referendum

The referendum would go ahead, but since the impeachment vote failed, the Congress of People's Deputies sought to set new terms for a popular referendum. The legislature's version of the referendum asked whether citizens had confidence in Yeltsin, approved of his reforms, and supported early presidential and legislative elections. The parliament voted that in order to win, the president would need to obtain 50 percent of the whole electorate, rather than 50 percent of those actually voting, to avoid an early presidential election.

This time, the Constitutional Court supported Yeltsin and ruled that the president required only a simple majority on two issues: confidence in him, and economic and social policy; he would need the support of half the electorate in order to call new parliamentary and presidential elections.

On April 25 a majority of voters expressed confidence in the president and called for new legislative elections. Yeltsin termed the results a mandate for him to continue in power. Before the referendum, Yeltsin had promised to resign, if the electorate failed to express confidence in his policies. Although this permitted the president to declare that the population supported him, not the parliament, Yeltsin lacked a constitutional mechanism to implement his victory. As before, the president had to appeal to the people over the heads of the legislature.

The constitutional convention

In an attempt to outmaneuver the parliament, Yeltsin decreed the creation of a large conference of political leaders from a wide range of government institutions, regions, public organizations, and political parties in June— a "special constitutional convention" to examine the draft constitution that he had presented in April. After much hesitation, the Constitutional Committee of the Congress of People's Deputies decided to participate and present its own draft constitution. Of course, the two main drafts contained contrary views of legislative-executive relations.

Some 700 representatives at the conference ultimately adopted a draft constitution on July 12 that envisaged a bicameral legislature and the dissolution of the congress. But because the convention's draft of the constitution would dissolve the congress, there was little likelihood that the congress would vote itself into oblivion. The Supreme Soviet immediately rejected the draft and declared that the Congress of People's Deputies was the supreme lawmaking body and hence would decide on the new constitution.

The parliament was active in July, while the president was on vacation, and passed a number of decrees that revised economic policy in order to "end the division of society." It also launched investigations of key advisers of the president, accusing them of corruption. The president returned in August and declared that he would deploy all means, including circumventing the constitution, to achieve new parliamentary elections.

In July, the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation confirmed the election of Pyotr Sumin to head the administration of the Chelyabinsk oblast, something that Yeltsin had refused to accept. As a result, a situation of dual power existed in that region from July to October in 1993, with two administrations claiming legitimacy simultaneously. Another conflict involved the decision of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation regarding the regional presidency in Mordovia. The court delegated the question of legality of abolishing the post of the region's president to the Constitutional Court of Mordovia. As a result, popularly elected President Vasily Guslyannikov (member of the pro-Yeltsin Democratic Russia movement) lost his position. Thereafter, the state news agency ( ITAR-TASS) ceased to report on a number of Constitutional Court decisions.

The Supreme Soviet also tried to further foreign policies that differed from Yeltsin's line. Thus, on 9 July 1993, it passed a resolutions on Sevastopol, “confirming the Russian federal status” of the city. Ukraine saw its territorial integrity at stake and filed a complaint to the Security Council of the UN. Yeltsin condemned the resolution of the Supreme Soviet.

In August 1993, a commentator reflected on the situation as follows: “The President issues decrees as if there were no Supreme Soviet, and the Supreme Soviet suspends decrees as if there were no President.” ( Izvestiya, 13 August 1993).

Developments in September

The president launched his offensive on September 1 when he attempted to suspend Vice President Rutskoy, a key adversary. Rutskoy, elected on the same ticket as Yeltsin in 1991, was the president's automatic successor. A presidential spokesman said that he had been suspended because of "accusations of corruption." On September 3, the Supreme Soviet rejected Yeltsin's suspension of Rutskoy and referred the question to the Constitutional Court.

Two weeks later he declared that he would agree to call early presidential elections provided that the parliament also called elections. The parliament ignored him. On September 18, Yeltsin then named Yegor Gaidar, who had been forced out of office by parliamentary opposition in 1992, a deputy prime minister and a deputy premier for economic affairs. This appointment was unacceptable to the Supreme Soviet, which emphatically rejected it.

Siege and assault

On September 21, Yeltsin dissolved the Supreme Soviet, which was in contradiction with a number of articles of Russian Constitution of 1978 (with amendments of 1989—1993), e.g.:

Article 1216. The powers of the President of Russian Federation cannot be used to change national and state organization of Russian Federation, to dissolve or to interfere with the functioning of any elected organs of state power. In this case, his powers cease immediately.

In dissolving the Supreme Soviet, Yeltsin repeated his announcement of a constitutional referendum, and new legislative elections for December. He also scrapped the constitution, replacing it with one that gave him extraordinary executive powers. (According to the new plan, the lower house would have 450 deputies and be called the State Duma, the name of the Russian legislature before the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. The Federation Council, which would bring together representatives from the 89 subdivisions of the Russian Federation, would play the role of an upper house.)

Yeltsin claimed that by dissolving the Russian parliament in September 1993 he was clearing the tracks for a rapid transition to a functioning market economy. With this pledge, he received strong backing from the leading powers of the West. Yeltsin enjoyed a strong relationship with Western powers, particularly the United States, but the relationship made him unpopular with some Russians.

In Russia, the Yeltsin side had control over television, where hardly any pro-parliament views were expressed during the September–October crisis.

Parliament invalidates Yeltsin's presidency

Rutskoy called Yeltsin's move a step toward a coup d'etat. The next day, the Constitutional Court held that Yeltsin had violated the constitution and could be impeached. During an all-night session, chaired by Khasbulatov, parliament declared the president's decree null and void. Rutskoy was proclaimed president and took the oath on the constitution. He dismissed Yeltsin and the key ministers Pavel Grachev (defense), Nikolay Golushko (security), and Viktor Yerin (interior). Russia now had two presidents and two ministers of defense, security, and interior. It was dual power in earnest. Although Gennady Zyuganov and other top leaders of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation did not participate in the events, individual members of communist organizations actively supported the parliament.

On September 23, the Congress of People's deputies convened. Though only 638 deputies were present (the quorum was 689), Yeltsin was impeached by the Congress.

On September 24, an undaunted Yeltsin announced presidential elections for June 1994. The same day, the Congress of People's Deputies voted to hold simultaneous parliamentary and presidential elections by March 1994. Yeltsin scoffed at the parliament-backed proposal for simultaneous elections, and responded the next day by cutting off electricity, phone service, and hot water in the parliament building.

Mass protests and the barricading of the parliament

Yeltsin also sparked popular unrest with his dissolution of a parliament increasingly opposed to his neoliberal economic reforms. Tens of thousands of Russians marched in the streets of Moscow seeking to bolster the parliamentary cause. The demonstrators were protesting against the deteriorating living conditions under Yeltsin. Since 1989 GDP had declined by half. Corruption was rampant, violent crime was skyrocketing, medical services were collapsing, food and fuel were increasingly scarce and life expectancy was falling for all but a tiny handful of the population; moreover, Yeltsin was increasingly getting the blame. Outside Moscow, the Russian masses overall were confused and disorganized. Nonetheless, some of them also tried to voice their protest. Sporadic strikes took place across Russia. The protestors included supporters of various communist ( Labour Russia) and nationalist organizations, including those belonging to the National Salvation Front. A number of armed militants of Russian National Unity took part in the defense of the White House, as reportedly did veterans of Tiraspol and Riga OMON. The presence of Transnistrian forces, including the KGB detachment 'Dnestr', stirred General Alexander Lebed to protest against Transnistrian interference in Russia's internal affairs.

On September 28, Moscow saw the first bloody clashes between the special police and anti-Yeltsin demonstrators. Also on September 28, the Interior Ministry moved to seal off the parliament building. Barricades and wire were put around the building. On October 1, the Interior Ministry estimated that 600 fighting men with a large cache of arms had joined Yeltsin's political opponents in the parliament building.

Storming of the television premises

The leaders of parliament were still not discounting the prospects of a compromise with Yeltsin. The Russian Orthodox Church acted as a host to desultory discussions between representatives of the parliament and the president. The negotiations with the Russian Orthodox Patriarch as mediator continued until October 2. On the afternoon of October 3, Moscow police failed to control a demonstration near the White House, and the political impasse developed into armed conflict.

On October 2, supporters of parliament constructed barricades and blocked traffic on Moscow's main streets. On the afternoon of October 3, armed opponents of Yeltsin successfully stormed the police cordon around the White House territory, where the Russian parliament was barricaded. Paramilitaries from factions supporting the parliament, as well as a few units of the internal military (armed forces normally reporting to the Ministry of Interior), supported the Supreme Soviet.

Rutskoy greeted the crowds from the White House balcony, and urged them to form battalions and to go on to seize the mayor's office and the national television centre at Ostankino. Khasbulatov also called for the storming of the Kremlin and imprisoning “the criminal and usurper Yeltsin” in Matrosskaya Tishina. At 16:00 Yeltsin signed a decree introducing state of emergency in Moscow.

On the evening of October 3, after taking the mayor's office, pro-parliament demonstrators marched toward Ostankino, the television centre. But the pro-parliament crowds were met at the television complex by Interior Ministry units. A pitched battle followed. Part of the TV centre was significantly damaged. Television stations went off the air and 62 people were killed. Before midnight, the Interior Ministry's units had turned back the parliament loyalists.

When broadcasting resumed late in the evening, Yegor Gaidar called on television for a meeting in support of President Yeltsin. A number of people with different political convictions and interpretations over the causes of the crisis (such as Mikhail Gorbachev, Grigory Yavlinsky, Alexander Yakovlev, Yuri Luzhkov, Ales Adamovich, and Bulat Okudzhava) also appealed to support the government. Similarly, the Civic Union bloc of 'constructive opposition' issued a statement accusing the Supreme Soviet of having crossed the border separating political struggle from criminality. Several hundred of Yeltsin's supporters spent the night in the square in front of the Moscow City Hall preparing for further clashes, only to learn in the morning of October 4 that the army was on their side.

The storming of the Russian White House

Between October 2–4, the position of the army was the deciding factor. The military equivocated for several hours about how to respond to Yeltsin's call for action. By this time dozens of people had been killed and hundreds had been wounded.

Rutskoy, as a former general, appealed to some of his ex-colleagues. After all, many officers and especially rank-and-file soldiers had little sympathy for Yeltsin. But the supporters of the parliament did not send any emissaries to the barracks to recruit lower-ranking officer corps, making the fatal mistake of attempting to deliberate only among high-ranking military officials who already had close ties to parliamentary leaders. In the end, a prevailing bulk of the generals did not want to take their chances with a Rutskoy-Khasbulatov regime. Some generals had stated their intention to back the parliament, but at the last moment moved over to Yeltsin's side.

The plan of action was actually proposed by captain Gennady Zakharov. Ten tanks were to fire at the upper floors of the White House, with the aim of minimizing casualties but creating confusion and panic amongst the defenders. Then, special troops of the Vympel and Alpha units would storm the building. According to Yeltsin's bodyguard Alexander Korzhakov, firing on the upper floors was also necessary to scare off the snipers.

By sunrise on October 4, the Russian army encircled the parliament building, and a few hours later army tanks began to shell the White House. At 8:00 am Moscow time, Yeltsin's declaration was announced by his press service. Yeltsin declared:

Those, who went against the peaceful city and unleashed bloody slaughter, are criminals. But this is not only a crime of individual bandits and pogromshschiki. Everything that took place and is still taking place in Moscow is a pre-planned armed rebellion. It has been organized by Communist revanchists, Fascist leaders, a part of former deputies, the representatives of the Soviets.

Under the cover of negotiations they gathered forces, recruited bandit troops of mercenaries, who were accustomed to murders and violence. A petty gang of politicians attempted by armed force to impose their will on the entire country. The means by which they wanted to govern Russia have been shown to the entire world. These are the cynical lie, bribery. These are cobblestones, sharpened iron rods, automatic weapons and machine guns.

Those, who are waving red flags, again stained Russia with blood. They hoped for the unexpectedness, for the fact that their impudence and unprecedented cruelty will sow fear and confusion.

He also assured the listeners that:

Fascist-communist armed rebellion in Moscow shall be suppressed within the shortest period. The Russian state has necessary forces for this.

By noon, troops entered the White House and began to occupy it, floor by floor. Hostilities were stopped several times to allow some in the White House to leave. By mid-afternoon, popular resistance in the streets was completely suppressed, barring occasional sniper's fire.

Crushing the "second October Revolution," which, as mentioned, saw the deadliest street fighting in Moscow since 1917, cost hundreds of lives. Police said, on October 8, that 187 had died in the conflict and 437 had been wounded. Unofficial sources named much higher numbers: up to 2,000 dead.

Yeltsin was backed by the military only grudgingly, and at the eleventh hour. The instruments of coercion gained the most, and they would expect Yeltsin to reward them in the future. A paradigmatic example of this was General Pavel Grachev, who had demonstrated his loyalty during this crisis. Grachev became a key political figure, despite many years of charges that he was linked to corruption within the Russian military.

The crisis was a strong example of the problems of executive-legislative balance in Russia's presidential system, and, moreover, the likelihood of conflict of a zero-sum character and the absence of obvious mechanisms to resolve it. In the end, this was a battle of competing legitimacy of the executive and the legislature, won by the side that could muster the support of the ultimate instruments of coercion.

Public opinion on crisis

The Russian public opinion research institute VCIOM (VTsIOM) conducted a poll in the aftermath of October 1993 events and found out that 51% of those polled thought that the use of military force by Yeltsin was justified and 30% thought it was not justified. The support for Yeltsin's actions declined in the later years. When VCIOM-A asked the same question in 2003, only 20% agreed with the use of the military, with 57% opposed.

When asked about the main cause of the events of October 3–4, 46% in the 1993 VCIOM poll blamed Rutskoy and Khasbulatov. However, ten years following the crisis, the most popular culprit was the legacy of Mikhail Gorbachev with 31%, closely followed by Yeltsin's policies with 29%.

In 1993, a majority of Russians considered the events of September 21 – October 4 as an attempt of Communist revanche or as a result of Rutskoy and Khasbulatov seeking personal power. Ten years thereafter, it became more common to see the cause of those events in the resolution of Yeltsin’s government to implement the privatization program, which gave large pieces of all-nation property to a limited number of tycoons (later called “oligarchs”), and to which the old Parliament (Supreme Soviet) was the main obstacle.

Yeltsin's consolidation of power

The end of the first constitutional period

On December 12, Yeltsin managed to push through his new constitution, creating a strong presidency and giving the president sweeping powers to issue decrees. (For details on the constitution passed in 1993 see the Constitution and government structure of Russia.)

However, the parliament elected on the same day (with a turnout of about 53%) delivered a stunning rebuke to his neoliberal economic program. Candidates identified with Yeltsin's economic policies were overwhelmed by a huge protest vote, the bulk of which was divided between the Communists (who mostly drew their support from industrial workers, out-of-work bureaucrats, some professionals, and pensioners) and the ultra-nationalists (who drew their support from disaffected elements of the lower middle classes). Unexpectedly, the most surprising insurgent group proved to be the ultranationalist Liberal Democratic Party led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky. It gained 23% of the vote while the Gaidar led ' Russia's Choice' received 15.5% and the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, 12.4%. LDPR leader, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, alarmed many observers abroad with his neo-fascist, chauvinist declarations.

Nevertheless, the referendum marked the end of the constitutional period defined by the constitution adopted by the Russian SFSR in 1978, which was amended many times while Russia was a part of Mikhail Gorbachev's Soviet Union. (For further details on the change of political and economic system of the former Soviet Union, see History of the Soviet Union (1985–1991).) Although Russia would emerge as a dual presidential-parliamentary system in theory, substantial power would rest in the president's hands. Russia now has a prime minister who heads a cabinet and directs the administration, but the system is an example of presidentialism with the cover of a presidential prime minister, not an effective semipresidential constitutional model. (The premier, for example, is appointed, and in effect freely dismissed, by the president.)