Amazon - Website

|

Project Gutenberg

Australia a treasure-trove of literature treasure found hidden with no evidence of ownership |

BROWSE the site for other works by this author (and our other authors) or SEARCH the entire site with Google Site Search |

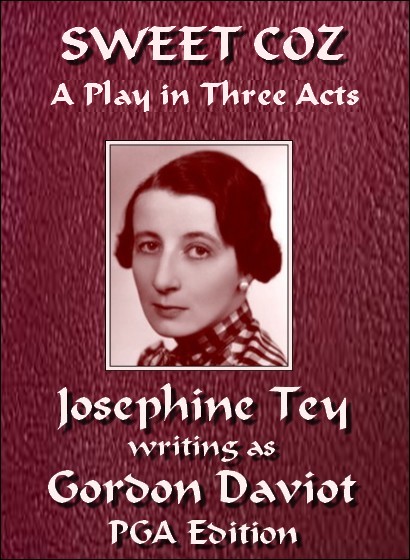

Title: Sweet Coz Author: Josephine Tey (writing as Gordon Daviot) * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 1600291h.html Language: English Date first posted: March 2016 Most recent update: March 2016 This eBook was produced by Colin Choat and Roy Glashan Project Gutenberg of Australia eBooks are created from printed editions which are in the public domain in Australia, unless a copyright notice is included. We do NOT keep any eBooks in compliance with a particular paper edition. Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this file. This eBook is made available at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Australia Licence which may be viewed online.

GO TO Project Gutenberg Australia HOME PAGE

CHARACTERS

DINAH PARTRIDGE

HECTOR PARTRIDGE

JOB

MRS BINT

JEMIMA CLAMP

ACT I

The living-room of a small flat on a morning in early Spring. It is a

pleasant room, modern in furnishing and decoration without being

mannered. It is also a woman's room, without being particularly

feminine. In the rear wall is the entrance to the passage, off which are

the bedrooms. In the left wall the fireplace, with an electric fire

burning. In the right wall the window, and down from it the door to the

vestibule and kitchen.

A table near the fire is half-set for breakfast.

Enter MRS BINT.

MRS BINT 'obliged' for years, owing to the 'ongoings' of her husband,

but when she met DINAH PARTRIDGE she ceased 'obliging' and slept in,

and so became a housekeeper. At the moment she is carrying a tray filled

with what she calls 'the rest of the dry things'. That is, with

everything necessary for breakfast except the actual food. She mutters

to herself in a worried fashion as she lays the things. When she has

finished she lingers in front of the table and tries what is apparently

a rehearsal.

MRS BINT: (addressing an imaginary presence behind the table) If it's

all the same to you, miss, I'd like to—(Trying again) I'm sorry to

say it, miss, but I've decided—(She gives it up for the moment,

fetches a chair, places it on the side nearest the fire, and tries

again) Things bein' as they are, miss, I think it's only right to tell

you—(She pauses and gives it up once more. She picks up a teaspoon

from the saucer, beats on the edge of the saucer with it, replaces it,

and goes out to fetch the rest of the things. She comes back with a

substantial breakfast for one: coffee, eggs and bacon, and toast. No one

has come from the bedroom, so she beats a second tattoo with the spoon

and waits with it poised)

DINAH: (off) Coming!

[As MRS BINT is setting out the dishes, DINAH comes in from the

passage. She is twenty-eight; good-looking without being a beauty,

tailored without being mannish, independent without being

farouche. A pleasant creature; just a little smug, just a little

professionally bright, just a little too conscious of 'owing not

any man'. But charming withal.]

DINAH: (brightly) Good morning, Mrs Bint.

MRS BINT: (with reserve) Good morning, miss.

DINAH: (making straight for the table, with a glance at the clock as

she comes) Nearly half-past eight, I observe. That is the result of an

evening out. It is just as well that Annual Balls are annual. Is this

the new bacon?

MRS BINT: That's the new bacon, miss.

DINAH: Still very fat. Tell Rapson we like some protein.

MRS BINT: Yes, miss.

DINAH: (eating) It's very warm in here. You might turn down the fire

a little. What is the outside temperature?

MRS BINT: I don't know. I haven't looked this morning.

DINAH: (mildly) Look now, then.

MRS BINT: (crossing to the window and opening it) I don't know what a

drop of mercury's likely to know about the weather.

DINAH: (scenting the atmosphere) Your lumbago troubling you this

morning, Mrs Bint?

MRS BINT: No, thank you, I've no lumbago. (She looks at the glass

hanging outside the window and gives the figure)

DINAH: Mild for February. Everyone will be wanting tonics. Any

telephones when I was out last night, Mrs Bint?

MRS BINT: Just one. The message is on the pad.

DINAH: What did it say?

MRS BINT: It said that Mrs Snitcher's stomach's settled nicely.

DINAH: I find it in my heart to envy Mrs Snitcher. Either I am getting

too old for Hospital Balls, or I am developing a liver. I forgot to look

at my tongue this morning. All right, Mrs Bint, you needn't wait. Do

what you like about dinner. I'm too late to think about it. Chops,

fillet of sole, anything.

MRS BINT: If I could speak to you for a minute, miss.

DINAH: Won't it keep till tonight, you masterpiece of worry?

MRS BINT: No, miss, I'd like to get it off my chest.

DINAH: What is it? A breakage?

MRS BINT: Oh, no. There ain't nothing broken.

DINAH: Don't tell me your husband has turned up again.

MRS BINT: Oh, no. According to the law of averages he ain't due yet a

bit.

DINAH: What is it then?

MRS BINT: (taking her fence with a rush) I should like to give a

week's notice dating from today, miss.

DINAH: Mrs Bint! Why? Are you ill, or something?

MRS BINT: No, miss. I'm very well, thank you.

DINAH: Then why do you want to leave me? All suddenly like this. Have I

said anything to offend you?

MRS BINT: No, it ain't anything you said—

DINAH: I know I'm crotchety sometimes, but you must make allowances. In

my job the stink of iodoform gets into one's hair. You have always made

allowances so far. We have always agreed so well, I thought you—

MRS BINT: Oh, yes, miss, I'm not denying that. A nicer lady in the way

of manners you couldn't meet—

DINAH: I thought you had been so happy this last year—

MRS BINT: I have, miss, I have indeed. After obliging by the day for

twenty years, it's been a grand life. I've always said so, and I shall

always continue to say so. You've been very kind to me, and a nicer lady

to work for there never was.

DINAH: (losing her poise) Then if I'm an angel with seven haloes,

what in thunder do you want to leave me for?

MRS BINT: I don't want to. I'm driven to it. You see, everyone has

something they won't stand for. Some doesn't like green, and some gets

sick at the sight of snails, and—

DINAH: And what, may I ask, is your breaking-point?

MRS BINT: Riotous living.

DINAH: (taken aback) What!

MRS BINT: Maybe I'm narrow-minded, but that's the way I was brought up,

and I can't help it any more than I can help the size of my feet. I'm a

respectable woman.

DINAH: (dryly) No one ever doubted it. And if you refer to the goings

on of the artist creature in Number Forty, I can't see how riotous

living up two flights of stairs can make any—

MRS BINT: (portentous with meaning) I was referring to events

nearer home, miss.

DINAH: (having stared at her, incredulous) Do you seriously mean that

you are giving me notice because for once I've had a night out?

MRS BINT: I'm sorry, miss, but I won't countenance light living.

DINAH: Light living! My God! I go to bed at eleven o'clock for three

hundred and sixty-four nights in the year, and because I come home with

the milk on the three hundred and sixty-fifth you give me notice. It's

unbelievable.

MRS BINT: It isn't just the coming in late—

DINAH: (with heavy sarcasm) No, no, of course not; it's the

immorality of it all. (Coldly) Very well, Mrs Bint, if you want to

leave me, of course, I accept your notice.

MRS BINT: I'm very sorry, miss. Of course, though I say a week, that

doesn't mean that I won't stay till you're suited. I wouldn't—

DINAH: I shall telephone the agencies this morning, and by the end of

the week I shall no doubt have someone to take your place. Until then I

hope that you can steel your conscience sufficiently to condone my

purple life. Will you see if the porter has brought up the morning

paper.

MRS BINT: I'd just like to say, miss, that I deeply regret—

DINAH: Don't say anything, Mrs Bint.

MRS BINT: Very good, miss. How many shall I prepare dinner for?

DINAH: (faintly surprised) Just for myself, as usual.

MRS BINT: (faintly surprised in turn) Oh? Very good, miss. Shall I

take some breakfast to the gentleman?

DINAH: (who has resumed her breakfast, pausing) What? What gentleman?

MRS BINT: The gentleman you brought home last night.

DINAH: Have you taken leave of your senses?

MRS BINT: (with a trace of smugness) Not me, I haven't, miss.

DINAH: Do you seriously mean that--that someone stayed the night here?

MRS BINT: Had you forgotten him, miss?

DINAH: Forgotten? I don't even remember br—I don't believe it! Who

was it?

MRS BINT: A complete stranger to me, miss.

DINAH: When did you see him?

MRS BINT: When I took his boots off. They were spoiling Mr Hector's

eiderdown, and Mr Hector's that particular.

DINAH: You mean he was drunk?

MRS BINT: Paralytic.

DINAH: (in a small voice) I might as well tell you, Mrs Bint, that I

have no recollection at all of coming home last night. It's most

extraordinary. Complete aphasia. I think I must have been overworking.

MRS BINT: (judicially) Well, some calls it that.

DINAH: Did I seem--did I seem quite normal?

MRS BINT: All but.

DINAH: But what?

MRS BINT: A strong smell of gin and a look in your eye.

DINAH: But if he was as drunk as that how did I—? Did you? Did

I—?

MRS BINT: The taxi-man put him to bed. You gave him a fiver.

DINAH: (reviewing it; with conviction) I must have been drunk.

MRS BINT: It was worth it. He's no bantam, your gentleman friend.

DINAH: I didn't mean the money. Great heavens, what a mess. And you

mean that the man is actually in there at this moment?

[From the distance comes the crash of broken glass.]

MRS BINT: I think that's him now. (There is the sound of movement in

the passage) If you'll excuse me, miss—

DINAH: No, don't go, Mrs Bint, don't leave me.

MRS BINT: But wouldn't it be better—?

DINAH: Stay where you are.

[From the passage door there enters tentatively a tall, unshaven

figure clad in an expensive dressing-gown that is much too small

for him, shabby trousers, brilliant bedroom slippers of the sort

that are only sole and toe, and a muffler that matches the

dressing-gown. He is bearing in one hand the remains of a

drinking-glass.

[And since for the rest of the play he is to be known as JOB, he

may as well be called JOB straight away.]

JOB: Good morning.

DINAH: Good morning.

JOB: I'm afraid I've broken a tumbler.

DINAH: Oh, that's all right. It--they're quite inexpensive.

JOB: I found the dressing-gown in the wardrobe.

DINAH: Yes. Yes, it's my brother's.

JOB: Thank God! (In reply to her eyebrows) I was afraid it was your

husband's.

DINAH: (unable to take her eyes off him) I must have been very

drunk.

JOB: I look better when I'm shaved.

DINAH: (hastily) I didn't mean that.

[There is an awkward pause.]

MRS BINT: (briskly, into the silence) Bacon and egg, ham and egg,

scrambled eggs, or plain boiled.

JOB: Oh, thank you. Whatever is going.

[Exit MRS BINT.]

DINAH: Won't you sit down.

JOB: Thank you.

DINAH: I hope you slept well?

JOB: Very well indeed, thank you. A most comfortable bed. And you?

DINAH: Oh, I always sleep well.

JOB: A most enviable accomplishment.

DINAH: (into a pause) Would you like to begin on the toast while Mrs

Bint is getting your eggs?

JOB: Good idea. Thank you.

DINAH: Did you enjoy the ball?

JOB: The ball?

DINAH: Last night.

JOB: I don't think I was there.

DINAH: Oh.

JOB: Should I have been?

DINAH: Well, I naturally thought—(That it was there we met, she is

going to say, but recollects herself) Most people go.

JOB: I have always been deficient in the herd instinct. One of my

greatest weaknesses.

DINAH: Really? What are your others?

JOB: Scotch, Irish, rye, and bourbon. Fair play: what are yours?

DINAH: (seeing a chance to entrench) I--I do the oddest things.

JOB: Yes, I thought swimming was a little odd.

DINAH: Swimming? (As he crunches his toast heartily) You did say

swimming?

JOB: It's just as well that I didn't listen to you, or we'd both have

pneumonia this morning.

DINAH: Yes, perhaps you were right. (Remembering that if she is at a

disadvantage where the early history of the evening is concerned, he at

least can have no recollection of the end; brightly) It was kind of you

to see me home.

JOB: Oh. Oh, that was nothing. I was delighted.

DINAH: (pleased to have him doing the groping for a change) I'm sorry

you missed your last train.

JOB: Train? Oh, it didn't matter. It was charming of you to put me up.

DINAH: I hope you didn't have to be at business early this morning.

JOB: Not at all. If I appeared in the office more than once a week

there would be a sensation.

DINAH: What office is that?

JOB: National Relief.

DINAH: (at a loss again) A most interesting work.

JOB: You know, it is a shocking thing to say to one's hostess, but I

can't remember your name.

DINAH: My name is Partridge. Dinah Partridge.

JOB: Thank you. A charming bird. So modest and--and plump.

DINAH: (busy deciding that she will not confess to being unaware of

his name) Expensive though.

JOB: I had not contemplated it from the point of view of possession.

(Before she can consider that) What a very lucky thing for me that

your brother was not at home!

DINAH: (unguardedly) And for me!

JOB: What?

DINAH: (retrieving) I hate making up couch beds in the small hours of

the morning. And Hector wouldn't share his bed with anyone.

JOB: (savouring it) Hector.

DINAH: Hector is my brother.

JOB: I can hardly blame your brother. It is a very pretty bed. Is

Hector a house decorator?

DINAH: No, he is a poet.

JOB: That might explain it.

DINAH: Explain what?

JOB: The bed. What kind of poet is he, by the way? 'And the reluctant

moon slid down the sky'? That kind? Or

'Six sticks

And why and wherefore

Corrugated, corrugated,

Because

And the cat's whiskers'?

DINAH: Do you mean that you don't know Hector?

JOB: (anxiously) Did I say that I did?

DINAH: Oh, no. But most people seem to. He wrote Pink Daffodils, you

know.

JOB: (politely reverent) No, I didn't know.

DINAH: Do you care for reading?

JOB: I find it useful.

[Enter MRS BINT with breakfast.]

DINAH: Ah, here is your breakfast.

JOB: (staring) And when do you expect your brother back?

DINAH: Tomorrow, I hope.

JOB: Ah, that looks marvellous. What a very good cook you keep.

[MRS BINT sniffs and goes out.]

JOB: That missed the mark, I think.

DINAH: (coldly) Probably. It was Mrs Bint who took your boots off

last night.

JOB: Oh, then it wasn't you who put me to bed?

DINAH: (indignant) Certainly not! Why should you imagine that I

would?

JOB: Women are apt to become officious with a helpless male body at

their disposal.

DINAH: The male body is no treat to me. It's my profession.

JOB: (staring) I can't believe it! You look so—

DINAH: I'm a doctor.

JOB: (genuinely shocked) Good God!

DINAH: And what is Good God about it?

JOB: It makes me feel very undressed.

DINAH: Does that worry you?

JOB: No woman should know as much as that about any man. It isn't in

nature. You probably take one look at me and decide that I am suffering

from cirrhosis of the liver, hernia, and chronic constipation.

DINAH: No. You are suffering from malnutrition, alcoholic poisoning,

the after-effects of pneumonia and incipient phthisis.

JOB: (after the slightest pause) You are a very good doctor.

(Resuming his poise) And a charming hostess. I have never enjoyed a

breakfast so much. I'm afraid you are not making much headway with

yours.

DINAH: I am not very hungry this morning. I—It is not very often

I—(The whole enormity of the situation floods over her in a rush,

and to her horror she finds tears rising)

JOB: Are you crying, by any chance?

DINAH: (indignantly) No! (Equally indignantly) Yes! Yes, I'm

crying, and why shouldn't I? I feel awful. I think I'm going to die.

JOB: For a doctor who has just made an excellent diagnosis I think that

prognostication is nothing short of disgraceful.

DINAH: (who is now crying openly into her handkerchief) Oh, don't be

so pompous!

JOB: If you'll tell me where the whisky is, I'll prescribe without

pomp, charge, or delay.

DINAH: I don't keep whisky in the flat. The stimulant habit is a very

bad one.

JOB: Don't tell me you are T.T. Not after last night.

DINAH: Of course not. There is plenty of wine, but only for drinking

with meals.

JOB: And what, may I ask, do you usually do in a situation like this?

DINAH: I've never been in a situation like this before.

JOB: Oh, please don't cry. I'll go directly after breakfast.

DINAH: (unmollified) Of course you will! If that were all. Mrs Bint's

given notice because of you.

JOB: Because of you, you mean.

DINAH: Me!

JOB: I didn't bring home any strange man at three in the morning. (As

this produces a fresh burst of grief) Oh, my sweet partridge, so modest

and plump and expensive, please don't take on. If it will make you any

happier I shall jump out of the window.

DINAH: I should only have you in hospital.

JOB: If I jumped very hard I might make it the morgue.

DINAH: You couldn't.

JOB: Why not?

DINAH: It's only the first floor. Oh, dear, I haven't cried since I

left school.

JOB: You seem to be doing a lot of things for the first time in

twenty-four hours.

[The telephone rings.]

DINAH: (mopping her eyes and going to the telephone) And now I shall

have to go round the agencies, and it's practically impossible to get

anyone for housework. (Blowing her nose and lifting the receiver)

Hullo. Who?... Oh, Doctor Simmons. Good morning.... Yes, of course I'm

all right. Why shouldn't I be?... What nonsense!... What utter

nonsense!... Yes, certainly I am.... I never had a hangover in my life,

thank you.... What?... No, just a touch of catarrh.... Yes, certainly I

shall be at hospital at my usual hour. (Slams down the receiver)

Little whippersnapper!

JOB: He sounded very considerate.

DINAH: (furious) He said I was the sweetest case of acute alcoholism

he had ever seen. (As JOB laughs; viciously) He wasn't very kind

about you either. He said he wouldn't have guessed my condition--my

condition, indeed!--if it hadn't been for the pupils of my eyes, and my

taking a fancy to a frightful man at a coffee stall. He had to leave me

there, he says, because I wouldn't come away. He wanted to know if I was

all right.

JOB: And you said you had catarrh.

DINAH: So that is where I met you?

JOB: At Toni's. Yes. Had you forgotten?

DINAH: (luxuriating in the truth) I haven't the faintest recollection

of ever seeing you before in my life.

JOB: You mean you don't remember any of last night?

DINAH: (less certainly) Is there much to remember?

JOB: Well, up to the point when I passed out myself it seemed to me a

pretty full evening. I thought I knew this town fairly well, but you

certainly showed me round.

DINAH: I showed you round!

JOB: And for a woman who doesn't keep whisky on tap, you gave a brave

display. I give you best, lady. No one has drunk me under the table in

twenty years.

DINAH: Eat your eggs. They're getting cold. (She pours away her cold

coffee and pours out fresh)

JOB: So I wasn't the only one who was surprised this morning.

DINAH: Were you surprised?

JOB: I was practically paralysed. I don't usually waken up in bedrooms

like Hector's.

DINAH: What did you think?

JOB: Well, after I had considered the pillows, I decided that I was

being rescued.

DINAH: The pillows?

JOB: Yes; the other one was virgin, you see. And then, after some deep

research, I remembered everything from Toni's up to the fire—

DINAH: Fire?

JOB: The fire at Timpson's warehouse.

DINAH: Were we there?

JOB: We were. And I decided that, all things considered, it couldn't be

rescue. Just bed and breakfast and no strings. The awkward part of it

was that you didn't have a face.

DINAH: A face!

JOB: I could see you arguing with the fire-engine man—

DINAH: What was I arguing about?

JOB: You wanted to buy his boots.

DINAH: What on earth for?

JOB: To grow geraniums in, you said. But you didn't have any face. You

didn't seem to have any face in anything we did together. So all I

could do was to purloin a dressing-gown and do some investigating.

DINAH: (still with the same dream-like detachment) And did you

recognise me?

JOB: I don't say I would have spotted you at a football match, but as

between you and Mrs Whatshername it was a cinch.

DINAH: (considering it) It must have been overwork.

JOB: What must?

DINAH: My performance last night.

JOB: Or the Spring, shall we say?

DINAH: Nonsense. I've been through a lot of Springs.

JOB: I suppose Spring to a doctor is merely a matter of purgatives.

Primrose in the hedgerows and treacle and brimstone in the home. Your

poor children! Never a picnic outside a given radius from a public

convenience.

DINAH: (stung) I take it that your progeny, if you have any, greet

the flowering year by flitting fairy-like from bud to bud.

JOB: I haven't any, but that is how they would carry on--approximately.

DINAH: How charming. I hope you won't carry on too much when you have

to pay.

JOB: Pay what?

DINAH: Bills for shoe-leather and fines for uprooting blue-bells.

JOB: You have a mundane mind. It distresses me. Last night you tilted

at every windmill, you threw your bonnet over and ran to catch it on the

other side, you were young and gay and—

DINAH: And drunk.

JOB: And now you sit there insisting that two and two make four.

DINAH: (coldly) I find it the most convenient reckoning.

JOB: Convenience! Expedience! Are these the gods of your idolatry! You

who were so—

DINAH: Have some mustard. That bacon is very fat. And if I tell you

that my middle name is Martha it may save a lot of misunderstanding in

the future.

JOB: The future?

DINAH: (flashing out) For the rest of this abominable breakfast. (In

a sudden burst; glad to find a scapegoat) Have you ever considered

the creature?

JOB: (startled) Who?

DINAH: Mary! The smug, selfish, good-for-nothing! Being soulful in

the parlour while Martha sweated in the kitchen.

JOB: Dinah, you shock me. What is a dish of curried mutton compared

with an idea?

DINAH: Nothing; if your stomach's full. Have you ever thought that

Martha was struggling with supper for about twenty while Mary was

sitting with her hands folded about an Idea? And don't tell me this

world is built on ideas, because it isn't. It's built on Martha. If it

weren't for Martha we'd still be living in caves.

JOB: But Mary is older than the caves, my dear, much older. When the

first mud-puppy crawled out of the primeval slime, that was Mary moved

by a great idea.

DINAH: Not at all. It was Martha deciding that higher up the hill was

better for the children.

JOB: I suppose that Socrates drank the hemlock merely to get away from

his wife's tongue—

DINAH: I wouldn't wonder—

JOB: --and Columbus, what did Columbus sail for? Curiosity?

DINAH: Columbus sailed for ten per cent of the gross receipts, and he

refused to leave harbour till the contract was water-tight.

JOB: (smiling at her) Were you born like that, or has living with a

Mary reduced you to Marthadom?

DINAH: Living with one?

JOB: I take it that Hector, being a poet, is a Mary.

DINAH: You don't know much about poets, do you? Poets are the most

practical people on earth.

JOB: How nice for you. Do they scramble their own eggs when they come

to supper?

DINAH: Oh, we don't have poets here.

JOB: Don't talk as if they were bugs.

DINAH: Poets don't like each other, you know.

JOB: Oh. Do doctors?

DINAH: (considering it) Yes. We disapprove of each other, but we are

quite friendly.

JOB: What made you become a doctor? (His tone says: 'You of all

people')

DINAH: I wasn't made to.

JOB: Oh. Did you have a 'call'?

DINAH: No; I had a quite normal belief that I could do something a

great deal better than it had been done before.

JOB: But why doctoring?

DINAH: That seemed the department where stupidity was most rampant.

JOB: Had you forgotten Parliament?

DINAH: No. But if I must deal with wind I would rather deal with it in

the stomach. It's curable there.

JOB: The Goddess of Common Sense.

DINAH: (amending) Good sense. It's not very common. What is your

profession, by the way?

JOB: I'm a window-box weeder.

DINAH: I merely asked.

JOB: In the summer, that is. In winter I make the holes in crumpets.

DINAH: I suggest that next winter you do it in Switzerland. (Rising)

And now I must go, or Clamp will be coming to look for me.

JOB: Oh, don't go yet. Please. It won't matter if you are late for

once. I'm quite sure you have never been as much as thirty seconds late

since first you went to that hospital.

DINAH: (beginning to collect the various articles she has brought in

with her and thrown on the sofa; hat, coat, gloves, and bag) No, I

haven't.

JOB: Then it is high time you were. No one appreciates an automaton.

I'm sorry I was fresh about my profession—

DINAH: You had every right to be. What you do is no proper concern of

mine.

JOB: It wasn't meant to be snubbing. One gets into the habit of

flippancy.

DINAH: And anyhow, I have no time to listen to the story of anyone's

life at this hour of the morning.

JOB: Perhaps not. But there is no need for any mystery about me. I was

an architect.

DINAH: (relaxing slightly to interest) Why 'was'?

JOB: Because to be an architect one must build things. And it is a long

time since I built anything.

DINAH: Were you a good architect?

JOB: Yes.

DINAH: What did you build?

JOB: Houses mostly. And I did a good theatre once. And then there was a

competition--for a county hall. Something good for itself, and good for

the fellow that did it. I put aside everything for that. I was cocksure

of getting it. Well, I didn't. And on the day I heard I had lost, my

wife left me for another man. I don't blame her; for months I hadn't

even noticed that she was around. I drank solidly for five weeks; then I

had pneumonia, as you so shrewdly observed. And now I pick up a living

by drawing straight lines on paper for other men.

DINAH: I see. You didn't have to tell me, you know.

JOB: Yes, I had to. I'm sorry, in a way. I think you're that woman in

every hundred who doesn't like a failure. You hate failure in

yourself--that's why you cried with rage this morning--and—

DINAH: It wasn't with rage!

JOB: --you despise it in others. However, last night changed my whole

life for me. I am beginning new this morning. No more coffee-stall

dinners at Toni's, no more drawing straight lines for other men. You

have opened new prospects to me.

DINAH: What prospects?

JOB: Blackmail, of course.

DINAH: I should have thought of that and poisoned your breakfast.

JOB: It's bad to have bodies around.

DINAH: Not when you can sign the death certificate.

JOB: Even dead, I would take a lot of explaining to Hector.

DINAH: (at the window) Yes, the car is there. I must go. Clamp

mustn't come in and find you here.

JOB: Can't Mrs Whatshername tell your chauffeur to wait a little?

DINAH: Good gracious, Clamp isn't my chauffeur. She's the head masseuse

at hospital. She happens to live upstairs, and so she gives me a lift to

hospital in the mornings.

JOB: Gives you a lift! You mean the nurse has a car and the doctor

walks? You're not much of a blackmail prospect, are you?

DINAH: Oh, we have a car, but Hector has it in the country. And don't

ever let Clamp hear you call her a nurse. I'll leave you to finish your

breakfast. You'd better begin all over again and have it in peace.

(Catching sight of herself in a mirror) Heavens, what a face! (Begins

some hasty repairs)

JOB: Tell me: there's just one thing: if we ever happen to meet in the

street, do we know each other?

DINAH: (without turning) Why not? You sold me that terrier bitch I

gave my cousin last year.

JOB: Oh, did I? That's nice. I can stop and ask about the dog, can't I?

DINAH: In moderation. You'll find cigarettes in the box. You won't stay

too long, will you? Mrs Bint is very upset about last night,

and--well—

JOB: I shall be gone in half an hour. I'm sorry I couldn't meet Hector.

Do you like Hector, by the way?

DINAH: Like him? Of course I like him!

JOB: Why of course?

DINAH: He's my brother, isn't he?

JOB: That's the oddest reason for liking anyone that I ever—

DINAH: (snatching up her gloves) You know, Clamp is the salt of the

earth, but I shudder to think what she would make of the present

situation if she were to walk in and find this domestic scene—

CLAMP: (off) Dinah!

DINAH: Merciful heaven, there she is!

[Enter JEMIMA CLAMP.

[CLAMP is square, solid, and uncompromising, and her formidable

muscles are rapidly being smoothed over by comfortable fat. She

has a level eye and wildly unbecoming clothes.

[She is carrying a square cardboard box, and she comes into the room

as an habitu? does, without looking round; aware only that

DINAH is there, and talking to her without looking at her,

meanwhile depositing her parcel on the side table between the

window and the door.]

CLAMP: If you don't hurry up, Dinah, you're going to create a record by

being late! I've brought you some of the eggs that my farm woman—(As

she turns from the table to the room again she sees JOB) Oh, pardon

me!

DINAH: Oh, Clamp dear, I'm sorry to keep you, but things are in a

muddle this morning. I don't think you have met my cousin, have you?

CLAMP: (shaking hands) Oh, are you George?

DINAH: No; no, this is Job.

CLAMP: (accepting it) I never knew you had a cousin called Job.

DINAH: He's just home from Siam.

CLAMP: (to JOB) Oh. Teak, I suppose.

JOB: No, twins. Statistics, you know.

CLAMP: Oh, yes. The incidence of the phenomenon.

JOB: Eh? Oh, yes. Quite.

CLAMP: That's very interesting. And what is the incidence, if you don't

mind my asking?

JOB: Point nought six per thousand.

CLAMP: As low as that! Why do they call them Siamese, then?

JOB: Because they began there. The climate, you know.

CLAMP: (intelligently, but with a shade of doubt) Oh, I see.

DINAH: I'm ready, Clamp.

CLAMP: (making no move) Well, now that you're home, perhaps Dinah

will step out a little more, and stop spending her evenings with

Beaumont and company.

JOB: Who is Beaumont?

CLAMP: Aren't you a doctor?

JOB: God forbid.

CLAMP: But, those twins and things?

JOB: Oh, that's Civil Service.

CLAMP: Is it, indeed. (That is comment, not question) Yes, I suppose

it is. Just counting things. Imagine being paid for just counting.

Something you do with beads in the kindergarten. (Hastily) Not that I

don't mean you were probably very good at it. Present company, and all

that.

DINAH: Clamp, my dear—

JOB: You haven't told me about this Beaumont she spends her leisure

with.

CLAMP: What she usually spends her leisure with is Hector's socks,

but—

DINAH: Oh, Clamp dear, don't be ridiculous. You know Hector would never

dream of wearing anything that was darned!

CLAMP: I was speaking in parables. She's much too clever, really, for

Beaumont—

JOB: But who—

CLAMP: (in patient explanation) We--ll, if you're a doctor, and you

can't decide whether your patient has malaria, D.T.s, or paralysis, you

say: 'Forgive me for a moment', and you jink into the office and look up

Beaumont.

JOB: I see.

CLAMP: Doctor's lifebelt, that's Beaumont. Other folks' too, if they

only knew it. And when you've decided between the mumps and the malaria,

there's the prescription all ready for you to write down when you get

back to the surgery, with the proper air of: 'Now, let me see. We

might try—' (In the course of her tale her eye has fallen on

DINAH. She stops abruptly, stares, and resumes in a tone of accusing

ferocity. To DINAH) I told you not to wear that frock!

DINAH: What frock?

CLAMP: Last night. Half a dozen miserable yards of tulle to cover your

body on a February evening--and now look at you!

DINAH: What's the matter with me?

CLAMP: A nose like an electric bulb, and eyes like a dribbling spaniel.

Have you gargled?

DINAH: I haven't got a cold, you fool, I've only been sneezing.

CLAMP: Have you gargled?

DINAH: (losing her temper) No! I gargled yesterday, and I'll gargle

tomorrow, but today I was rushed, and getting to my job on time is much

more important than swilling a little permanganate round my throat.

CLAMP: And so the whole of hospital has to be strewn with germs so that

you can clock in at—

DINAH: I can gargle in hospital, can't I? Come along.

CLAMP: And meanwhile, I suppose, I get enough germs in my car to put my

department out of action for a fortnight—

DINAH: Come along!

CLAMP: Doctor Partridge, you gargle or walk.

DINAH: (evidently recognising the tone) Oh, blast you! (She flings

down her bag and gloves again and dashes angrily through the passage

door)

CLAMP: (in her normal voice, to JOB) It was a pretty frock, wasn't

it? (She moves over to inspect the breakfast-table)

JOB: Lovely.

CLAMP: (helping herself to a scone and buttering it) Me, I've never

been able to wear a frill without bringing ham to people's minds, but I

like to see other women look nice. Women don't have so much of a time.

JOB: Don't they?

CLAMP: No, they don't, take it from me. I think, bar God, no one hears

so many sad tales from women as I do.

JOB: But tales aren't evidence, are they?

CLAMP: Oh, I'm dealing with the evidence while they're telling the

tale.

JOB: Ah, well, perhaps it's retribution. It's thanks to a woman we were

all thrown out of the Garden.

CLAMP: What authority are you quoting?

JOB: The Bible, of course.

CLAMP: According to the Bible, we were thrown out because a man

couldn't say no to something he wanted. You hadn't finished your

breakfast. Go on. Don't mind me.

JOB: (amused) Would you like some more coffee too? (As well as her

scone, he means)

CLAMP: I shouldn't mind a spot. (She pours the slops into DINAH'S

cup, and uses the slop-basin as cup) What was the matter with Dinah's

eggs?

JOB: I think she's feeling a little after-the-ball, you know.

CLAMP: (with a snort) H'm! She should go dancing oftener, then. Take

it in homeopathic doses. Now that you have stopped counting twins for a

bit, perhaps— (Struck by a horrible thought) Don't tell me you are

a devoted husband with a large family?

JOB: No, I'm neither a husband nor a father. But why should Dinah need

to be rescued by me? Aren't there any followers?

CLAMP: Weren't you at the ball?

JOB: Well, then. What's to hinder her going out every night of her

life?

CLAMP: Nothing. Nothing. Except the biggest obstacle of all.

JOB: What is that?

CLAMP: She likes staying at home. Can you imagine it? A woman who can

look the way she did last night 'liking to stay at home'! If I could

look like that I'd hire a float to convey me round town for a couple of

hours every night, like a holy image, so that no one would miss having a

good look.

JOB: A woman who likes staying at home is so rare, I think that she

should be encouraged.

CLAMP: Encouraged! Huh! Encouraged to take a nerve tonic and get

herself some vitality. (Reaching over and dabbing some marmalade on the

buttered scone she is eating) It's all that little blood-sucker,

Hector!

JOB: So you don't like Hector?

CLAMP: (pausing to stare at him) Does anyone like Hector?

JOB: Dinah seems to.

CLAMP: Oh, Dinah is daffy about him. 'My baby brother', and all that.

Baby brother! Man-sized boa-constrictor.

JOB: Tell me, have you read Pink Daffodils?

CLAMP: I have not. Neither has anyone else.

JOB: Is it not a success, then?

CLAMP: Oh, yes, people buy it. But that's as far as they go. I think

maybe Mrs Transom-Sills has read it.

JOB: Mrs—Who is she?

CLAMP: She is Hector's steady.

JOB: Oh. And is there a Mr Transom-Sills?

CLAMP: Not since the Grisons avalanche in '36.

JOB: Rich widow?

CLAMP: Very rich and quite a widow.

JOB: Then why doesn't Hector marry her?

CLAMP: Hector doesn't like being bothered, if you know what I mean.

JOB: Do I know what you mean?

CLAMP: I mean, Hector has been wrapped in cotton-wool so long that some

real fresh air on his skin would probably kill him. If he married Mrs

Transom-Sills he couldn't run home to Dinah any more, every time someone

kicked him in the pants.

JOB: Doesn't the widow keep a good brand of embrocation?

CLAMP: If she does it's for her own skin. She's a sensible woman.

That's what's wrong. Hector doesn't want a sensible woman, he wants an

unselfish fool like Dinah. And they don't grow on bushes. Don't think me

personal, will you, but is that Hector's dressing-gown you're wearing?

JOB: It is.

CLAMP: Cast-off? I mean, did he give it to you?

JOB: Oh, no, I found it in his room.

CLAMP: Then take a tip from a friend and don't be wearing it when he

comes home tomorrow, or there'll be another row for Dinah to smoothe

over. If he thought someone had worn it, he'd probably have prickly

heat.

JOB: Right now it's giving me leprosy.

CLAMP: What's wrong with your own one?

JOB: I haven't got one. Not here, I mean. I saw Dinah home last night,

you see, and it was so late that she put me up.

CLAMP: I suppose that meant Hector's pyjamas as well.

JOB: Not--not exactly.

CLAMP: And what does exactly mean?

JOB: I sleep in my skin. Siam, you know.

CLAMP: Why blame Siam? And while we're on the subject, I don't believe

that statistics story. What did you really do in Siam?

JOB: Drank.

CLAMP: And what else?

JOB: And drank.

CLAMP: The statistics on that must be staggering.

JOB: You have a genius for the right word.

CLAMP: It seems a long way to go just to drink. Halfway to China, isn't

it?

JOB: If one goes that way.

CLAMP: Is there another way?

JOB: One could go west, I suppose.

CLAMP: (dismissing it) Oh, well, who wants to go to China anyhow?

JOB: (murmuring) Standard Oil, maybe.

CLAMP: (summing up the Chinese empire) Floods, and rice, and people

flying kites.

JOB: I think sailing a paper boat among the clouds is an endearing

pastime.

CLAMP: They must fall over quite a bit.

JOB: I would rather fall over because I had my eyes on the sky than

because I lost my balance kicking a muddy ball.

CLAMP: I expect the ground feels the same. And the tetanus.

JOB: Is your middle name Martha?

CLAMP: No, Kedge. Jemima Kedge Clamp. You don't have to mind. I stopped

minding, myself, about twenty-five.

JOB: What cured you?

CLAMP: I found I could change it. Legally, you know. After that I

stopped worrying. It's wonderful what you can put up with when you don't

have to. Look at sport. If a man was condemned to have his feet tied to

skids and be shoved off a snow mountain for hours every day, so that he

was all black and blue, he'd yell his head off with rage. But if he does

it of his own accord that's all right. That's skiing, that is. Do you

ski?

JOB: No, I curl.

CLAMP: Curl what? Oh, yes; pushing stones about on ice. That's a sissy

sort of amusement for a man your size.

JOB: (stung) What ought I to do? Balance elephants on the tip of my

tongue? What is Hector's game, by the way?

CLAMP: Tag. How long is it since you saw Hector?

JOB: Oh, long time.

CLAMP: I shouldn't say you had much in common.

JOB: No. No, we haven't. Not even an acquaintance.

CLAMP: That's no great loss.

JOB: Are Hector's acquaintances not what is called desirable?

CLAMP: Only the way house-agents use the word. You know: This desirable

residence. Lovely outside, and crawling with beetles inside.

[DINAH comes hurrying back, to find her boon companion and her

colleague happily having breakfast together.]

DINAH: Well! I thought you were in a hurry.

CLAMP: Not me. I'm never in a hurry to get to hospital.

DINAH: Oh, come along, Clamp.

CLAMP: What you will never learn, Dinah, is that neither of us is in

the least necessary to that place.

DINAH: Stop talking nonsense and eating other people's food, and—

CLAMP: The higher up you get in your job, the less you count. If we

were both struck by lightning this minute, it wouldn't cause a ripple in

the day's work.

DINAH: Speak for yourself.

CLAMP: It's the rank and file that keep the world going, not geniuses

like you and me.

DINAH: You're just talking so that you can eat another scone. For

Heaven's sake, will you pull yourself together and let us go. I'll get

Mrs Bint to make you a whole baking to yourself if you'll only—

CLAMP: When?

DINAH: Tomorrow.

CLAMP: I may be dead tomorrow.

DINAH: This evening. Any time you like.

CLAMP: (preparing to make a move) Well, that's a good offer. I

suppose we might as well get along anyhow. We have to go sometime. (To

JOB; referring to a remnant of scone) Do you want that half? No? In

that case, I'll take it with me. Dinah can drive, and I'll eat. I

suppose, not being in the profession, you've never known the glory of

putting your patients on a diet that you have no intention of using

yourself. Well, I'll see you soon again, I expect. Perhaps you and Dinah

will come upstairs and have a drink with me after dinner tonight?

DINAH: Oh, Job is not staying.

CLAMP: (to JOB) But you're in town, aren't you?

JOB: Only to see my tailor and my dentist, like a little gentleman.

CLAMP: Oh, well, you'll be along to see Hector when he comes back

tomorrow, I expect, so I won't say good-bye.

[DINAH and JOB turn to each other, but before either can say a

word of farewell there is the sound of the outer door of the flat

being closed with a bang.]

CLAMP: Mrs Bint doesn't seem her sunny self this morning.

DINAH: (faintly) I think someone's come in.

[There are the sounds of a man's voice in converse with MRS BINT.]

CLAMP: It sounds like our future Poet Laureate.

DINAH: (in a wild wail) But it can't be!

CLAMP: (arrested by the tone) Why not?

DINAH: He's not coming back till tomorrow.

CLAMP: Perhaps there weren't enough peeresses at that place. He always

gets a temperature if there aren't enough peeresses.

[Enter HECTOR.

[When HECTOR was three people stopped his perambulator in the

street to gloat over his beauty. At seventeen he looked very much

as he looked in his perambulator: cherubic and charming. At

twenty-six he looks merely an elderly baby; his contours blurred a

little by incipient adipose tissue, his pink-and-white complexion

gone a little yellow, his hair growing already thin. His manner

varies from pompousness when he is not at ease to a na?ve

trustfulness which is the last remnant of his boyish 'charm'.

Speaking generally, he is of the type that most women want to

'shield' from life, and most men want to kick into the middle of

next week.]

DINAH: Hector! What is it? Are you ill?

HECTOR: (staring; in a cold drawl) No, I am not ill--yet. Would

someone explain what that man is doing in my dressing-gown?

CURTAIN

ACT II

Scene and time are continuous with the previous Act.

HECTOR: What is that man doing in my dressing-gown?

DINAH: Oh, Hector, this is the younger of the two Butchard boys.

HECTOR: And since when have you entertained the tradesmen to breakfast?

DINAH: Butchard, darling; with a D.... Aunt Cicely's boys.

HECTOR: Aunt Cicely's name was Bartholomew.

DINAH: Only after she married the bishop. The carpet manufacturer was

Butchard. This is Job, the younger of the two small boys who used to

play with us at Bude, you remember.

JOB: How are you, Hector? I can hardly blame you for not remembering

me.

HECTOR: Your hair used to be red.

DINAH: No, darling, Alan was the red one.

HECTOR: But I remember most distinctly—

DINAH: You were only five last time you saw him, so you can't remember

very much.

JOB: And I have done nothing to make myself memorable, I'm afraid. I

know all about you, of course.

HECTOR: I hope you don't boast about me. I hate being boasted about by

people I don't know.

JOB: On the contrary; I keep you dark.

HECTOR: You keep me dark?

JOB: One looks very shabby against a brilliant relation. I can't even

live up to your bath-slippers, my dear Hector. As for your bed, I have

never felt so embarrassed as I did in its embrace. During our brief

relationship it was one well-bred and silent protest.

DINAH: (hastily) I refused to let Job go out again last night. He

took me home from the hospital affair, and it was very late and bitterly

cold.

HECTOR: I can see it was very late. You are not looking your best this

morning, Dinah.

CLAMP: (instantly) You don't look too chippy yourself, Hector.

Temperature, I shouldn't wonder.

DINAH: Are you ill, Hector? Is that why you cut your visit short?

HECTOR: I cut it short because I was bored. Bored. Bored.

JOB: Cousin Hector, you thrill me. I never met anyone who was bored

with such passion that he fled from it at seven in the morning.

HECTOR: (beginning to take off his coat) You have obviously never

stayed in a house with Shatty Pixton. She came down last night, and as

soon as I heard that she was coming I said to Tina: 'If that woman is to

be here I shall go.' Tina thought I was merely being amusing. But she

will know differently by now. Or will in about an hour, when she wakens

up. It is too bad of Tina. She knows very well what I think of Shatty

and all her poisonous crowd. It surprises me that she would even have

them under her roof. They are not in the same world as Tina.

CLAMP: (for JOB'S benefit) Tina is the Duchess of Frisby; spelt

Featherstoneborough.

[Enter MRS BINT.]

MRS BINT: What will Mr Hector have for breakfast?

HECTOR: Coffee. Nothing but coffee.

DINAH: But Hector, you must have a proper breakfast if you left Friston

so early. Have you had anything at all?

HECTOR: I had early-morning tea. Even that choked me.

DINAH: Mrs Bint will make you some fresh scones. They won't take a

moment.

HECTOR: Will you stop fussing, Dinah. I'll have coffee. A great deal of

coffee. And then I shall go to bed. (To JOB) You have finished with

my bed?

JOB: Oh, quite, quite. I am afraid the room is very untidy. I shall go

and clear up.

HECTOR: Mrs Bint will do that.

[Exit MRS BINT to the kitchen, taking with her the remains of

breakfast.]

JOB: But I'm still wearing your dressing-gown. I had better—

HECTOR: You may wear it a little longer.

JOB: Thank you.

HECTOR: It will conduce to a cosy atmosphere while you explain

yourself.

JOB: Explain myself?

HECTOR: You are my long-lost cousin, and you have been dancing with

Dinah. That leaves some gaps to be filled, doesn't it?

DINAH: You won't forget that you have that dentist's appointment at

ten, will you, Job?

JOB: Oh, that is for tomorrow.

DINAH: (staggered by his refusal of her lifeline) Then it is the

tailor today.

JOB: No, I have no appointment this morning.

DINAH: (dismayed) But you said most distinctly—

HECTOR: Don't be so possessive, Dinah. I know that you saw him first,

but he is equally related to me. Things which are equal to one another

are equal to the same thing. I forget whether that is an axiom or a

theorem.

JOB: It's equally embarrassing either way.

HECTOR: You and Miss Clamp run along to your hospital, and leave us to

look after ourselves.

CLAMP: He has known me for four years, and he still calls me Miss

Clamp. It's by way of protest.

HECTOR: Protest against what?

CLAMP: The existence of women like me.

DINAH: I must speak to Mrs Bint. Clamp, be an angel and (indicating

the telephone) tell them I shall be a little late.

[Exit DINAH to kitchen.]

JOB: (as CLAMP dials a number; to HECTOR, who is considering him)

Am I coming back to you?

HECTOR: Your name used to be John, surely?

JOB: Yes; it still is. Job is merely the way I used to say my name when

I was small, and my version stuck.

CLAMP: (at telephone) A message for the matron. Tell her that Doctor

Partridge will not be—Hullo? Who are you, may I ask?... Oh. Are you

hanging round that telephone board again, Doctor Simmons? (JOB'S ears

prick at the name) Let me tell you, that girl is engaged to a detective

sergeant, six foot two in his socks.

HECTOR: (who has taken a letter from the mantelpiece and is opening

it) The contrast between the private amusements of the medical

profession and their more public moments has always struck me as being

highly entertaining.

JOB: (with one ear on the telephone conversation) Nothing to the

Church.

CLAMP: (at the telephone) Of course she's coming! She's just going to

be a little late.

JOB: I had an uncle who used to make breakfast a hell for everyone, an

hour before he preached a moving sermon on patience and brotherly love.

HECTOR: What uncle was that?

CLAMP: (at the telephone) Sober? Don't be silly. Did you ever know

her when she wasn't sober?

JOB: Oh, a brother of my father's.

CLAMP: (at the telephone) What!

JOB: (hastily; talking for the sake of talking, while he watches

CLAMP'S face as she listens to SIMMONS'S story) He had a living in

Devon. Quite a character, he was. Wrote some books, I believe. Volumes

of sermons, or something like that. They like to write something so that

they can appear as the frontispiece. Ever noticed how like actors they

look?

HECTOR: Who?

JOB: The clergy. Fundamentally, I suppose, it is the same thing. It's

just a toss-up whether the inspiration is God or the prompt corner.

HECTOR: You're not an actor, then?

JOB: Good God, no. Do I look like one?

HECTOR: It had crossed my mind. Which of the Dominions do you come

from?

JOB: If not an actor, then certainly a remittance man.

HECTOR: Not at all. Only, long-lost cousins usually come from the

bounds of Empire.

JOB: I'm from Siam.

HECTOR: You needn't be defiant about it. I have learned to accept the

improbable with equanimity.

JOB: I'm an architect.

HECTOR: Oh. Bungalows in Bangkok.

JOB: Something like that.

CLAMP: (contemplating JOB with a new eye, and slowly replacing the

receiver) Do you know a coffee-bar called Toni's--in Bangkok?

JOB: Very well. That is where the woman was murdered.

CLAMP: What woman?

JOB: Oh, some woman who knew too much. She was put out of the way to

prevent her talking.

CLAMP: All women don't talk.

JOB: No?

CLAMP: No!

[Enter DINAH; and from the expression on her face the interview

with MRS BINT would appear to have been satisfactory.]

DINAH: Clamp, don't wait for me. There is no need for you to be late

too. Now that Hector has brought back the car I can drive myself. (To

JOB) And perhaps I can give Job a lift into town. (To CLAMP) Did you

get the hospital?

CLAMP: Yes. I talked to Doctor Simmons.

DINAH: (arrested) Doctor Simmons!

CLAMP: (smoothly) He's hanging round that switchboard girl, you know.

DINAH: (doubtfully) Yes. Yes; did he say--did he say if there was

anything urgent?

CLAMP: He said a lot, but nothing of medical interest. His mind seems

to be still full of last night.

DINAH: (viciously) If his stomach is still full of last night he

could hardly be talking sense.

CLAMP: (with an air of taking no sides) It seems to have been a very

wet night altogether.

HECTOR: I've always understood that that was the aim of a Hospital

Ball; that and charity. It must be so comforting when one is being sick

in hospital to know that the utensil was paid for by the sickness of the

staff.

CLAMP: One of my dreams, Hector, is to have you as a patient. There's a

new gadget in the south clinic that I never use without thinking of you.

(Taking her leave) Well, I hope to know you better, Mr--Mr—

DINAH: Butchard.

CLAMP: Mr Butchard. You seem to be an enterprising young man. (With

the faintest flick of an eyelash in the direction of HECTOR) It's a

breed that seems to be growing scarce these days.

DINAH: Wait, Clamp, I'll come along with you after all, I think.

CLAMP: (airily) Don't let me hurry you, Dinah. Now you've got the

car—

DINAH: (in a last appeal) Job, can't we give you a lift to town?

JOB: Thank you, Dinah, but now that Hector has arrived so

providentially I look forward to making his acquaintance.

DINAH: But Hector is going to bed—

HECTOR: Will you very kindly not interfere, Dinah. If Job and I choose

to have breakfast together—

DINAH: But he's had his breakfast.

HECTOR: Then he can smoke while I have mine—

DINAH: You know you hate people smoking while you are eating.

HECTOR: I wish you wouldn't be so possessive, Dinah darling.

DINAH: I'm not possessive. I'm just being sensible. If you want to go

to bed, what use is there in Job's staying? And if you go to bed there

won't be anyone to drive him into town, and—

HECTOR: There is a public service of omnibuses, I believe. And a fleet

of taxi-cabs at the end of a telephone wire. Really, Dinah! Run along to

your hospital, my dear girl, and leave your find with me. It's my turn

now.

DINAH: Oh, very well. Perhaps it is best that way, because you wouldn't

have much chance of seeing each other otherwise. Job is leaving town

tomorrow, to visit some other cousins. In Orkney.

HECTOR: Does anyone live in Orkney? I thought it was one of those

islands that are always evacuating themselves on to the mainland.

JOB: (since something seems to be expected of him) At the last census

the population was fifty-three thousand and seven.

CLAMP: What was the seven for?

JOB: Accuracy.

CLAMP: I thought perhaps it was for luck.

HECTOR: But fifty thousand people can't all gather gulls' eggs. What

do they do?

JOB: Well, my cousins burn seaweed.

HECTOR: Bonfires. How nice!

JOB: No; they smell. In fact, they smell so badly that I don't think I

can bring myself to go at all.

DINAH: Job! Think--think how you will disappoint the little one with

the stammer.

JOB: But I always catch a stammer if I stay with one for any length of

time. No, on second thoughts, between the smell and the stammer, I don't

think I shall go after all.

CLAMP: (ironic) I shouldn't. You might find the climate trying--after

Siam.

[Exit CLAMP.]

DINAH: Nonsense. It's bracing and—(Noticing that CLAMP has gone)

Oh, I must go. Clamp—(Her thought is obviously: I can't allow CLAMP

to get away) I shall be so late. Oh, Job—

JOB: Yes?

HECTOR: Did you get the new notepaper, Dinah?

DINAH: Yes, it's coming tomorrow.

HECTOR: The pale grey, I hope.

DINAH: Yes, the pale grey.

HECTOR: And what did the man say about the radiator?

DINAH: He said it would be quite simple, but rather expensive.

HECTOR: If it is a simple affair, how can it be expensive? The thing is

a contradiction in terms. If it is not going to be any trouble to do,

how—

DINAH: I don't know, Hector darling. That is what the engineer said.

I must go.

HECTOR: But didn't you—

DINAH: Yes, we discussed it for ages, back and fore and up and down,

and that's the answer. I must go. I have a lot to say to you, Job, but I

can't say it now.

JOB: Save it up till you have more time.

DINAH: Yes, I'll save it up.

[Exit DINAH.]

JOB: What a charming woman.

HECTOR: Who?

JOB: Dinah.

HECTOR: Do you think so? Most people find her a little farouche. She

seems extremely distrait this morning. Late nights don't agree with her.

Or perhaps it is you. Do you have an odd effect on people?

JOB: Not when I'm sober.

HECTOR: Some people are definitely allergic. I can tell when Shatty

Pixton has come into a room without turning my head.

JOB: What is so repellent about Miss Pixton?

HECTOR: (after a swift review of MISS PIXTON'S repellencies) She

gives imitations.

JOB: (visualising the imitation) Oh! (The tone says: 'That is surely

not all?')

HECTOR: She also reviews books.

JOB: Distressing; but not necessarily damning.

HECTOR: And she has the most evil tongue in London.

JOB: That certainly is a distinction. But a great poet like you should

be above things like that, surely? Were they so very bad?

HECTOR: Was what bad?

JOB: The imitation, the review, and the gossip.

HECTOR: (a little staggered, but mollified by the 'great poet'; with

exquisite pomp) There are some things no man can forgive.

JOB: (full of honey) Quite, quite.

HECTOR: (liking the honey) I suppose you don't know a game called

Labels?

JOB: No. No, that has not been one of my amusements.

HECTOR: Each person writes a label--preferably in rhyme--and the rest

tie it, metaphorically speaking, to the appropriate person. Well, Deenie

Stystable--Lord Manning's sister, you know--told me that they were

playing it one day at Wiskett--do you know Wiskett? A lovely place

looking out on the Vale of Aylesbury--and Shatty's label read:

'A frightful little blister

Who lives on his sister'.

JOB: And did they guess correctly?

HECTOR: Of course. Everyone knows that Shatty hates me like poison.

(Since JOB offers no immediate comment) I didn't think that in the

least funny.

JOB: (in a voice that would make anyone but HECTOR stand from

under) No; I don't think it is funny either.

HECTOR: It is intolerable that my devotion to Dinah should be

so--so—

[Enter MRS BINT with coffee and scones.]

HECTOR: (eyeing the covered scone dish with anticipation) What I

should like, Mrs Bint, would be some toast melba. I have no appetite,

but I feel the need of some sustenance.

MRS BINT: I made you a few scones, sir. I thought maybe—

HECTOR: Oh, no. No food.

MRS BINT: Very little, dainty ones, they are. Wouldn't stick in the

throat of a fly.

HECTOR: Oh, very well. I don't want to bother you to make toast if you

have already gone to the trouble of baking.

MRS BINT: Of course, if you're really pining, as you might say, for

that sawdust-tasting stuff, it won't take a minute to—

HECTOR: (hastily) No, no. Leave the scones. I'll make do with them.

MRS BINT: (with a baleful glance at JOB) I'll just tidy up your room,

sir.

HECTOR: (to JOB) Would you like more coffee?

JOB: Yes, I should. Very much. Mrs Bint makes excellent coffee.

HECTOR: Another cup for Mr Butchard, please.

[Exit MRS BINT to the kitchen.]

HECTOR: I wish her brother wasn't a lawyer.

JOB: Mrs Bint's!

HECTOR: No, Shatty's. What she says in print is always vetted by her

brother, and what she says in the course of a game is not actionable.

JOB: No libel on a Label.

HECTOR: No.

[Enter MRS BINT. As well as the extra cup, she is carrying a

string-bag, half the size of a potato sack, filled with letters.

She puts the cup on the table and deposits the sack on the floor

at HECTOR'S feet without remark. It is apparently a routine

proceeding. She then retires into the bedroom corridor with her

duster.]

JOB: (having stared at the letter-bag) Forgive my bluntness, my dear

Hector, but do you run a tipster's business on the side?

HECTOR: Oh, no. That is just the weekly mail.

JOB: My congratulations. I had no idea that anyone's poetry could raise

such public enthusiasm.

HECTOR: Poetry? You don't imagine that they write to me because of my

poems, do you?

JOB: Have you a side-line?

HECTOR: I have a Page. Don't you read me in the Daily Clarion on

Wednesdays?

JOB: I don't see much of the Press these days. In Siam, you see, they

only took The Times at the Club. And the Prince got only the

Bystander.

HECTOR: The Prince?

JOB: The man I was building the palace for. What do you write about in

your page?

HECTOR: Well, if I see a woman with a funny hat, I talk about that. And

they like God, in moderation. And royalty. And fashionable parties. And

people arriving at Southampton. Who was the Prince that you—

JOB: (indicating the sack) But what is all that about? Have you

appealed for something?

HECTOR: Oh, no. They just write and tell me how their asparagus is

coming on, and ask advice about little Jimmy's tonsils, and whether

they'd better tell Ida how Basil is carrying on in the evenings when she

is working. Ever since the Reformation the British have felt the lack of

a confessional, and now they have one. From the Press point of view,

it's the greatest discovery since the invention of printing.

JOB: And do you answer them?

HECTOR: My secretary does.

JOB: (with a glance round) Your secretary?

HECTOR: The Clarion send a girl down from the office. They intended

me to work at the office originally, but I declined. A desk between the

Gardening and the Fashions—! She did her nails all day, the Fashions.

Milson-Bleeson at the Telegram has a room to himself, and a private

lavatory. And Bines, at the Revally, has a whole floor. But of course

he's daily. By the time I've had another year at it I shall have a

better room than Milson-Bleeson's. Perhaps you could design it for me. I

didn't know you had been doing important work in Siam.

JOB: Oh, interesting, but not so important. Every house a royalty lives

in is called a palace in the East. Usually it's just a villa of forty or

fifty rooms. Actually the one I did for the Prince had sixty-four, but

that's a bit above the average. What kind of room had you in mind?

HECTOR: Well, Milson-Bleeson's looks like something out of an Embassy.

I should like mine to look like something out of the White House.

JOB: I see. Simple and distinguished. The ideal background.

HECTOR: (impervious to irony) Yes. Of course, I might succeed

Milson-Bleeson on the Telegram.

JOB: Is the gentleman slipping?

HECTOR: Yes. His heart is always breaking. His heart breaks at least

four times a page. Even for the British public that is a little too

sentimental. Dinah was dreadfully sentimental too.

JOB: Dinah?

HECTOR: When she did my letters. She—

JOB: You mean Dinah worked for the paper once?

HECTOR: No, no; not exactly. But when I first refused to work in that

office of theirs the Clarion were very peeved, and said that I should

have to find my own secretary.

JOB: (in a dangerous voice) And couldn't you find a secretary?

HECTOR: (blissfully unaware) Oh, Dinah loved doing it. It gave some

interest to her evenings. But she was always running amok and wanting to

investigate. The result of a scientific training on a naturally

sentimental mind.

JOB: What did she want to investigate?

HECTOR: Oh, if a man wrote that he hadn't the money for a pair of

boots, perhaps. She could never see that a man who hadn't the price of a

pair of boots could be of no interest to the Clarion. We run the page

for circulation purposes, not as a private charity.

JOB: We?

HECTOR: (conceding) They, then. (With a return to pomp at the hint

of criticism) Though I hope that as long as I am on the paper I am

loyal to it. (With a return to earth) Even if I go to the Telegram,

of course, I should insist on having that room of Milson-Bleeson's

redecorated. You are not going back to Siam, are you?

JOB: Oh, no. I came home to do a country house for a rich old woman who

died before I got here. Leaving me with the plans of the most beautiful

house I ever did, and no one to build it.

HECTOR: Perhaps I could get Deenie Stystable to build one. Is it large?

JOB: Oh, no. Only eleven rooms.

HECTOR: Five per cent of eleven rooms isn't much.

JOB: Five per cent?

HECTOR: My commission. But, still. You could line it with priceless

woods, couldn't you?

JOB: Actually I think I shall build it for myself. It is much too

beautiful to waste on any client.

HECTOR: Where are you living just now? At a hotel?

JOB: No. At rooms I had in my student days. Squalid, but full of

sentiment, and good enough till I find a house I like.

HECTOR: A flat, you mean.

JOB: Oh, no. A house. There is no cachet in a flat. An architect--in

fact, any man who works in the arts--needs a setting. A background, a

designed proportion, vistas, detail, a beauty made to measure. Not just

a--just a cell in a piece of honeycomb. Forgive me; I left my cigarettes

in my coat pocket.

[Exit JOB to the bedroom corridor.]

[HECTOR looks dubiously round the flat.

[At the door JOB passes MRS BINT, carrying sheets and duster

under one arm, and in the other hand his boots.

[HECTOR puts out his hand and absent-mindedly takes a letter from

the sack, but his thoughts are obviously still with this new idea

of himself as the inhabitant of a piece of honeycomb.]

MRS BINT: (pausing) Your bed's ready, Mr Hector. Will you be

requiring lunch, sir?

HECTOR: I should like some kidneys about two o'clock, I think.

MRS BINT: It's an awkward day for kidneys. You wouldn't like a nice

ripe steak, maybe?

HECTOR: No, I should like kidneys. Grilled. If our regular butcher

cannot supply them, go on telephoning till you find someone who can.

MRS BINT: Very good, sir. And how many will there be for lunch?

HECTOR: Oh, I don't think—(His eye comes to rest on JOB'S boots:

cracked, shapeless, and indescribably muddy. Unbelieving, he straightens

himself to have a better view) Where, in heaven's name, did you get

these?

MRS BINT: They belong to the gentleman, sir.

HECTOR: Am I to understand that these are the gentleman's

dancing-pumps?

MRS BINT: Oh, he didn't have evening things, sir.

HECTOR: You mean he went to the ball in those?

MRS BINT: I couldn't say, sir. That's what he came home in.

HECTOR: (taking the boots distastefully into a nearer view) Great

heavens, they're patched!

MRS BINT: (grimly) Not enough.

HECTOR: (recollecting himself) Thank you, Mrs Bint. (As she is going

to the door) What time did Mr Butchard arrive yesterday?

MRS BINT: Well--well, I couldn't exactly say, sir.

HECTOR: (coldly) Why couldn't you?

MRS BINT: (anxious for the well-loved black sheep) I don't usually

wait up for Miss Dinah.

HECTOR: Wait up?

MRS BINT: When she's out late.

HECTOR: Do you mean that it wasn't until this morning that

you—(Pulling himself up once more) Oh, very well, Mrs Bint. Thank

you.

[Exit MRS BINT, and JOB comes back with his cigarettes.]

HECTOR: (regarding JOB with a new eye, suspicion seething in him;

conversationally) I could have given you cigarettes.

JOB: Thank you, but it's so long since I smoked a good cigarette that I

should probably be sick.

HECTOR: Don't they keep good tobacco?

JOB: They?

HECTOR: In Siam.

JOB: Oh, in my part of the country men didn't smoke. It's considered

womanish. So I used to get secret supplies from an old planter in the

village who smoked nothing but the ten-a-penny brands.

HECTOR: What did he plant?

JOB: (hastily rejecting both rubber and tea, just in case) French

beans.

HECTOR: In Siam!

JOB: (firmly) Yes. They make a kind of chutney out of them. You can

get it at Fortnum's, I believe.

HECTOR: (threatening) I must ask for it.

JOB: (happily) Yes, do.

HECTOR: Did you enjoy the ball?

JOB: What ball?

HECTOR: Last night.

JOB: Oh, the hospital affair. I didn't go to it.

HECTOR: But you took my sister home from it!

JOB: (aware of the change of atmosphere, but not of its cause) Yes.

That was all.

HECTOR: Do you mind telling me how you met Dinah in the first place?

JOB: I just discovered her. In a reference book. It was my first

evening in London, you see, and I wanted some company, but there were so

many Partridges in the telephone book, and I couldn't ring them all up

because I had only tuppence—

HECTOR: Why had you only tuppence?

JOB: The rest of my money was French. I got off the boat at Marseilles,

and walked home across France. And the banks were shut, and my landlady

thought French notes much too pretty to be real money. And then I

remembered that at least one of you was a public character. (Watching

with delight HECTOR'S reaction) So I looked up Dinah in a public

library.

HECTOR: Dinah!

JOB: Yes, of course. You can always find a doctor. It told me all about

her qualifications--quite a clever girl, Dinah, isn't she?--but not her

private address. So I rang up the hospital where she was said to work,

and got my money's worth.

HECTOR: Your money's worth?

JOB: Value for my last tuppence. They said Doctor Partridge was there

at that moment, and they were having a dance, and wouldn't I come along.

So along I went, frayed trousers, cracked boots, empty pockets, and all.

But I needn't have worried. They're used to down-and-outs in hospital.

There's a little sister there with chestnut hair that made me long to

have typhoid.

HECTOR: Why typhoid?

JOB: I've always understood that that required the most constant

nursing. And when Dinah had finished being the belle of the ball—

HECTOR: Dinah!

JOB: Certainly. Don't you take her to dances? (Meaning: 'Don't you

know that she is always the belle of a ball?')

HECTOR: (stiffly) I don't dance, and Dinah does not care to. She goes

to hospital balls only because people would consider her impolite if she

didn't.

JOB: (heartily) People certainly considered her beautiful when she

did.

HECTOR: (having decided that anyone who invites suspicion so freely

and refutes it so impudently must be genuine, however odd his story;

testily) My dear Job! Dinah is a good creature, and I am very fond of

her, but she has never had more than the family share of good-looks.

(He turns to his letter)

JOB: Ah, but when a woman is happy—Have you never seen a bride with

a face like a turnip looking like Helen of Troy?

HECTOR: (without heat) I think brides are revolting. (Indicating the

sack of letters) Have you?

JOB: (picking a letter automatically) She was happy last night.

(Remembering it for the first time) She put her empty cup down on the

counter and smiled at me.

HECTOR: What counter?

JOB: Oh, they had a sort of canteen--cafetaria—(Reading) 'Darling

Hector'—Oh, I beg your pardon. (Offering him the letter)

HECTOR: (not taking it) Why?

JOB: It seems to be a personal letter.

HECTOR: Oh, no. Just someone who wants my photograph, probably.

JOB: (staring) What for? I mean, what do they do with it?

HECTOR: (suggesting, indifferently) Frame it, keep it under their

pillows—(With a shrug which says: 'How should I know?') Read it.

JOB: (reading) 'I want you to know that I have put your photograph on

a little altar I have made.' (That was one you didn't think of,

HECTOR) 'Whenever I want to be alone I go there and look at it and feel

better.' There are eight pages. Do you think God likes this

understudying of yours, Hector?

HECTOR: The Clarion likes it; that is all that concerns me. (As

JOB'S silence might imply disapproval) Can I help it if women are

silly about me?

JOB: (thoughtfully; dropping the letter back and taking another) No;

I suppose if it wasn't you it would be some Pekingese or other.

(Referring to HECTOR'S letter) What have you got?

HECTOR: (dropping his letter back and taking another) A free meal. I

must try the place sometime.

JOB: A meal for a mention?

HECTOR: Yes.

JOB: (having looked at his letter) Could you mention Mouldem corsets,

do you think?

HECTOR: What do they offer?

JOB: Their Mr Francis would like to show you over their model factory

in the country. Ten acres of gardens and the prettiest girls in five

counties.

HECTOR: Do they think I have nothing to do with my time but inspect

factories?

JOB: I suppose poetry is a full-time job. (He drops the letter and

takes another)

HECTOR: Being a successful poet is. One has obligations. To one's

publisher, if not to anyone else. No one buys the work of poets who sit

at home. By the way, is your Prince Whatshisname any relation of the

King of Siam?

JOB: The son of a first cousin.

HECTOR: (charmed) Indeed. Educated in England?

JOB: No.

HECTOR: How unfortunate.

JOB: In Japan.

HECTOR: How unfortunate. Does he come to this country at all?

JOB: No, he doesn't think it is safe.

HECTOR: Safe! England! Japanese propaganda.

JOB: No, it's his own idea. He saw the place on a map, and thinks it is

much too small. It might be swept into the sea at any moment.

(Referring to the letter in his hand) Someone is coming to the office

on Friday morning to knock your block off.

HECTOR: Why?

JOB: (studying the letter) You have been putting ideas into his

wife's head.

HECTOR: What! What ideas?

JOB: Making the best of herself. Apparently you have revealed the

existence of the belle laide. (Reading) 'My wife was born plain, and

I married her plain, and washing her hair and gaping'--no,

'gawping'--'in a mirror isn't going to do her nor me no good.'

HECTOR: Medieval. Quite medieval. You know, the average Briton would

have purdah tomorrow if he could.

JOB: The average Briton has a very hard fist.

HECTOR: Oh, I don't go to the office on Fridays. Besides, our doorman