Half-life

About this schools Wikipedia selection

This Schools selection was originally chosen by SOS Children for schools in the developing world without internet access. It is available as a intranet download. See http://www.soschildren.org/sponsor-a-child to find out about child sponsorship.

| Number of half-lives elapsed |

Fraction remaining |

Percentage remaining |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1/1 | 100 | |

| 1 | 1/2 | 50 | |

| 2 | 1/4 | 25 | |

| 3 | 1/8 | 12 | .5 |

| 4 | 1/16 | 6 | .25 |

| 5 | 1/32 | 3 | .125 |

| 6 | 1/64 | 1 | .563 |

| 7 | 1/128 | 0 | .781 |

| ... | ... | ... | |

| n | 1/2n | 100/(2n) | |

Half-life (t½) is the time required for a quantity to fall to half its value as measured at the beginning of the time period. In physics, it is typically used to describe a property of radioactive decay, but may be used to describe any quantity which follows an exponential decay.

The original term, dating to Ernest Rutherford's discovery of the principle in 1907, was "half-life period", which was shortened to "half-life" in the early 1950s.

Half-life is used to describe a quantity undergoing exponential decay, and is constant over the lifetime of the decaying quantity. It is a characteristic unit for the exponential decay equation. The term "half-life" may generically be used to refer to any period of time in which a quantity falls by half, even if the decay is not exponential. For a general introduction and description of exponential decay, see exponential decay. For a general introduction and description of non-exponential decay, see rate law.

The converse of half-life is doubling time.

The table on the right shows the reduction of a quantity in terms of the number of half-lives elapsed.

Probabilistic nature of half-life

A half-life usually describes the decay of discrete entities, such as radioactive atoms, which have unstable nuclei. In that case, it does not work to use the definition "half-life is the time required for exactly half of the entities to decay". For example, if there is just one radioactive atom with a half-life of one second, there will not be "one-half of an atom" left after one second. There will be either zero atoms left or one atom left, depending on whether or not that atom happened to decay.

Instead, the half-life is defined in terms of probability. It is the time when the expected value of the number of entities that have decayed is equal to half the original number. For example, one can start with a single radioactive atom, wait its half-life, and then check whether or not it has decayed. Perhaps it did, but perhaps it did not. But if this experiment is repeated again and again, it will be seen that - on average - it decays within the half-life 50% of the time.

In some experiments (such as the synthesis of a superheavy element), there is in fact only one radioactive atom produced at a time, with its lifetime individually measured. In this case, statistical analysis is required to infer the half-life. In other cases, a very large number of identical radioactive atoms decay in the measured time range. In this case, the law of large numbers ensures that the number of atoms that actually decay is approximately equal to the number of atoms that are expected to decay. In other words, with a large enough number of decaying atoms, the probabilistic aspects of the process could be neglected.

There are various simple exercises that demonstrate probabilistic decay, for example involving flipping coins or running a statistical computer program. For example, the image on the right is a simulation of many identical atoms undergoing radioactive decay. Note that after one half-life there are not exactly one-half of the atoms remaining, only approximately, because of the random variation in the process. However, with more atoms (right boxes), the overall decay is smoother and less random-looking than with fewer atoms (left boxes), in accordance with the law of large numbers.

Formulas for half-life in exponential decay

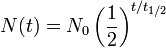

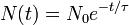

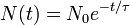

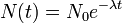

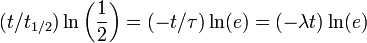

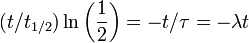

An exponential decay process can be described by any of the following three equivalent formulas:

where

-

- N0 is the initial quantity of the substance that will decay (this quantity may be measured in grams, moles, number of atoms, etc.),

- N(t) is the quantity that still remains and has not yet decayed after a time t,

- t1/2 is the half-life of the decaying quantity,

- τ is a positive number called the mean lifetime of the decaying quantity,

- λ is a positive number called the decay constant of the decaying quantity.

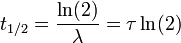

The three parameters  ,

,  , and λ are all directly related in the following way:

, and λ are all directly related in the following way:

where ln(2) is the natural logarithm of 2 (approximately 0.693).

-

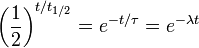

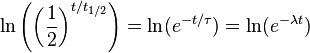

Click "show" to see a detailed derivation of the relationship between half-life, decay time, and decay constant. Start with the three equations We want to find a relationship between

,

,  , and λ, such that these three equations describe exactly the same exponential decay process. Comparing the equations, we find the following condition:

, and λ, such that these three equations describe exactly the same exponential decay process. Comparing the equations, we find the following condition:Next, we'll take the natural logarithm of each of these quantities.

Using the properties of logarithms, this simplifies to the following:

Since the natural logarithm of e is 1, we get:

Canceling the factor of t and plugging in

, the eventual result is:

, the eventual result is:

By plugging in and manipulating these relationships, we get all of the following equivalent descriptions of exponential decay, in terms of the half-life:

Regardless of how it's written, we can plug into the formula to get

as expected (this is the definition of "initial quantity")

as expected (this is the definition of "initial quantity") as expected (this is the definition of half-life)

as expected (this is the definition of half-life) , i.e. amount approaches zero as t approaches infinity as expected (the longer we wait, the less remains).

, i.e. amount approaches zero as t approaches infinity as expected (the longer we wait, the less remains).

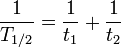

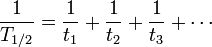

Decay by two or more processes

Some quantities decay by two exponential-decay processes simultaneously. In this case, the actual half-life T1/2 can be related to the half-lives t1 and t2 that the quantity would have if each of the decay processes acted in isolation:

For three or more processes, the analogous formula is:

For a proof of these formulas, see Decay by two or more processes.

Examples

There is a half-life describing any exponential-decay process. For example:

- The current flowing through an RC circuit or RL circuit decays with a half-life of

or

or  , respectively. For this example, the term half time might be used instead of "half life", but they mean the same thing.

, respectively. For this example, the term half time might be used instead of "half life", but they mean the same thing. - In a first-order chemical reaction, the half-life of the reactant is

, where λ is the reaction rate constant.

, where λ is the reaction rate constant. - In radioactive decay, the half-life is the length of time after which there is a 50% chance that an atom will have undergone nuclear decay. It varies depending on the atom type and isotope, and is usually determined experimentally. See List of nuclides.

the half life of a species is the time it takes for the concentration of the substance to fall to half of its initial value

Half-life in non-exponential decay

The decay of many physical quantities is not exponential—for example, the evaporation of water from a puddle, or (often) the chemical reaction of a molecule. In such cases, the half-life is defined the same way as before: as the time elapsed before half of the original quantity has decayed. However, unlike in an exponential decay, the half-life depends on the initial quantity, and the prospective half-life will change over time as the quantity decays.

As an example, the radioactive decay of carbon-14 is exponential with a half-life of 5730 years. A quantity of carbon-14 will decay to half of its original amount (on average) after 5730 years, regardless of how big or small the original quantity was. After another 5730 years, one-quarter of the original will remain. On the other hand, the time it will take a puddle to half-evaporate depends on how deep the puddle is. Perhaps a puddle of a certain size will evaporate down to half its original volume in one day. But on the second day, there is no reason to expect that one-quarter of the puddle will remain; in fact, it will probably be much less than that. This is an example where the half-life reduces as time goes on. (In other non-exponential decays, it can increase instead.)

The decay of a mixture of two or more materials which each decay exponentially, but with different half-lives, is not exponential. Mathematically, the sum of two exponential functions is not a single exponential function. A common example of such a situation is the waste of nuclear power stations, which is a mix of substances with vastly different half-lives. Consider a sample containing a rapidly decaying element A, with a half-life of 1 second, and a slowly decaying element B, with a half-life of one year. After a few seconds, almost all atoms of the element A have decayed after repeated halving of the initial total number of atoms; but very few of the atoms of element B will have decayed yet as only a tiny fraction of a half-life has elapsed. Thus, the mixture taken as a whole does not decay by halves.

Half-life in biology and pharmacology

A biological half-life or elimination half-life is the time it takes for a substance (drug, radioactive nuclide, or other) to lose one-half of its pharmacologic, physiologic, or radiological activity. In a medical context, the half-life may also describe the time that it takes for the concentration in blood plasma of a substance to reach one-half of its steady-state value (the "plasma half-life").

The relationship between the biological and plasma half-lives of a substance can be complex, due to factors including accumulation in tissues, active metabolites, and receptor interactions.

While a radioactive isotope decays almost perfectly according to so-called "first order kinetics" where the rate constant is a fixed number, the elimination of a substance from a living organism usually follows more complex chemical kinetics.

For example, the biological half-life of water in a human being is about 7 to 14 days, though this can be altered by his/her behaviour. The biological half-life of cesium in human beings is between one and four months. This can be shortened by feeding the person prussian blue, which acts as a solid ion exchanger that absorbs the cesium while releasing potassium ions in their place.