Library of Alexandria

Did you know...

This wikipedia selection has been chosen by volunteers helping SOS Children from Wikipedia for this Wikipedia Selection for schools. Click here for more information on SOS Children.

The Royal Library of Alexandria or Ancient Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was once the largest library in the ancient world.

The Library of Alexandria, generally thought to have been founded at the beginning of the Third century BC, was conceived and opened during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter, or that of his son Ptolemy II of Egypt. It has been reasonably established that the Library or parts of the collection were destroyed on a number of occasions, but to this day the details of the destruction (or destructions) remain a lively source of controversy based on inconclusive evidence. The Bibliotheca Alexandrina, an institution intended both as a commemoration and an emulation of the original, was inaugurated in 2003 near the site of the old Library.

The Library as a research institution

According to the earliest source of information, the pseudepigraphic Letter of Aristeas, the Library was initially organized by Demetrius of Phaleron, a student of Aristotle under the reign of Ptolemy Soter.

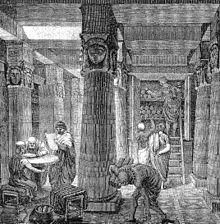

Built in the Brucheion (Royal Quarter) in the style of Aristotle's Lyceum , adjacent to and in service of the Musaeum (a Greek Temple or "House of Muses", where we get the term "museum"), the Library comprised a Peripatos walk, gardens, a room for shared dining, a reading room, lecture halls and meeting rooms. However, the exact layout is not known. This model's influence may still be seen today in the layout of university campuses. The library itself is known to have an acquisitions department (possibly built near the stacks, or for utility closer to the harbour), and a cataloguing department. The hall contained shelves for the collections of scrolls (as the books were at this time on papyrus scrolls), known as bibliothekai. Carved into the wall above the shelves, a famous inscription read: The place of the cure of the soul.

The first known library of its kind to gather a serious collection of books from beyond its country's borders, the Library at Alexandria was charged with collecting all the world's knowledge. It did so through an aggressive and well-funded royal mandate involving trips to the book fairs of Rhodes and Athens and a (potentially apocryphal or exaggerated) policy of pulling the books off every ship that came into port, keeping the originals and returning copies to their owners. This detail is informed by the fact that Alexandria, because of its man-made bidirectional port between the mainland and the Pharos island, welcomed trade from the East and West and soon found itself the international hub for trade, as well as the leading producer of papyrus and, soon enough, books.

Besides collecting works from the past, the library was also home to a host of international scholars, well-patronized by the Ptolemaic dynasty with travel, lodging and stipends for their whole families. As a research institution, the Library filled its stacks with new works in mathematics, astronomy, physics, natural sciences and other subjects. It was at the Library of Alexandria that the scientific method was first conceived and put into practice, and its empirical standards applied in one of the first and certainly strongest homes for serious textual criticism. As the same text often existed in several different versions, comparative textual criticism was crucial for ensuring their veracity. Once ascertained, canonical copies would then be made for scholars, royalty and wealthy bibliophiles the world over, this commerce bringing income to the library. The editors at the Library of Alexandria are especially well known for their work on Homeric texts, the more famous editors generally also holding the title of head librarian. These included, among others,

- Zenodotus (early third century BC)

- Apollonius of Rhodes (mid-third century BC)

- Eratosthenes (late third century BC)

- Aristophanes of Byzantium (early second century BC)

- Aristarchus of Samothrace (late second century BC)

Collection

The Greek term "biblioteke", used by many historians of the time, refers in fact to the [royal] "Collection of Books", not to the building itself, which complicates the history and chronology of its destruction. The Royal Collection can be viewed as having begun in the Royal Quarter's building, commonly known as "The Great Library", before being transferred to the library at the Sarapeum, an acropolis in the Egyptian quarter of town, home to the temple of Sarapis. The transfer occurred between Caesar's Fire of The Alexandrian War in 48bce and 272ce when the Royal Quarter was razed in the war with Zenobia. The collection remained at the Sarapeum until at least 391bce, the date of the destruction of the temple and specifically of the Sarapeum. It may have been destroyed by Theophilus' Christian mob as part of their destruction of the Sarapeum, or perhaps been maintained in its Sarapeum home. There is also a possibility that the collection was preserved in private libraries for years after. One debated account by Abd al Latif (1160-1231), a Muhamadan of letters, recounts the death of the collection at the hands of Omar: "The Academy erected by Alexander when he built this city, and in which he deposited the library consigned to the flames, with the permission of Omar, by 'Amr ibn el-As.(E.A. Parsons). Scholars, particularly 21st century Arab/Muslim scholars, contest this claim, whose veracity can be challenged alone on the basis that Alexander, although picking the site and planning the general layout of the city, died before he could have a hand in the erection of the library or academy therein.

Already famous in the ancient world, The Library's collection became even more storied in later years. However, it is now impossible to determine the collection's size in any era. Papyrus scrolls comprised the collection, and although parchment codices were used predominantly as a more advanced writing material after 300 BC, the Alexandrian Library is never documented as having switched to parchment, perhaps because of its strong links to the papyrus trade. (The Library of Alexandria in fact had an indirect cause in the creation of writing parchment - due to the library's critical need for papyrus, little was exported and thus an alternate source of copy material became essential.)

A single piece of writing might occupy several scrolls, and this division into self-contained "books" was a major aspect of editorial work. King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 BC) is said to have set 500,000 scrolls as an objective for the library. Mark Antony supposedly gave Cleopatra over 200,000 scrolls (taken from the great Library of Pergamum) for the Library as a wedding gift, but this is regarded by some historians as a propagandist claim meant to show Antony's allegiance to Egypt rather than Rome. Carl Sagan, in his series Cosmos, states that the Library contained nearly one million scrolls, though other experts have estimated a smaller number. No index of the Library survives, and it is not possible to know with certainty how large and how diverse the collection may have been. For example, it is likely that even if the Library had hundreds of thousands of scrolls (and thus perhaps tens of thousands of individual works), some of these would have been duplicate copies or alternate versions of the same texts.

A possibly apocryphal or exaggerated story concerns how the library's collection grew so large. By decree of Ptolemy III of Egypt, all visitors to the city were required to surrender all books and scrolls, as well as any form of written media in any language in their possession which, according to Galen, were listed under the heading "books of the ships". Official scribes then swiftly copied these writings, some copies proving so precise that the originals were put into the Library, and the copies delivered to the unsuspecting owners. This process also helped to create a reservoir of books in the relatively new city.

According to Galen, Ptolemy III requested permission from the Athenians to borrow the original scripts of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, for which the Athenians demanded the enormous amount of fifteen talents as guarantee. Ptolemy happily paid the fee but kept the original scripts for the library. This story may also be constructed erroneously to show the power of Alexandria over Athens.

Destruction of the Library

Ancient and modern sources identify four possible occasions for the destruction of the Library:

- Julius Caesar's Fire in The Alexandrian War, in 48 BC

- The attack of Aurelian in the Third century AD;

- The decree of Theophilus in 391 AD;

- The Muslim conquest in 642 AD or thereafter.

"It's inherently difficult to get reliable information about an event that consisted of the destruction of all recorded information," wrote Neal Stephenson in his December 1996 Wired magazine article, "Mother Earth Mother Board".

Caesar's conquest in 48 BC

Plutarch's Lives, written at the end of the first or beginning of the second century, describes a battle in which Caesar was forced to burn his own ships, which historian William Cherf proved had all the ingredients of a firestorm and in turn set fire to the docks and then the Library, destroying it. This would have occurred in 48 BC, during the fighting between Caesar and Ptolemy XIII. In the second century AD, the Roman historian Aulus Gellius wrote in his book Attic Nights that the Royal Alexandrian Library was burned by mistake when some Roman soldiers of Caesar’s troops set some fire. Furthermore, in the fourth century AD, both the pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus and the Christian historian Orosius agree that the Bibliotheca Alexandrina was destroyed by mistake following the fire that Caesar had begun. Caesar himself wrote in his book the Alexandrian Wars that the fires his soldiers had set to burn the Egyptian navy in the port of Alexandria went as far as burning a store full of papyri located near the port. However, the geographical study of the location of the historical Bibliotheca Alexandrina in the neighbourhood of Bruchion suggests that this store cannot be the Library. It is most probable here that these historians confused the two Greek words bibliothekas, which means “set of books” with bibliotheka, which means Library. As a result, they thought that what had been recorded earlier concerning the burning of some books stored near the port constituted the burning of the famous Alexandrian Library. In any case, whether the burned books were only some books found in storage or books found inside the library itself, the Roman stoic philosopher Seneca (c. 4 BC – 65 AD) refers to 40,000 books having been burnt at Alexandria. During Marcus Antonius' rule of the eastern part of the Empire (40-30 BC), he plundered the second largest library in the world (that at Pergamon) and presented the collection as a gift to Cleopatra as a replacement for the books lost to Caesar's fire.

| “ | The Roman galleys carrying the Thirty-Seventh Legion from Asia Minor had now reached the Egyptian coast, but because of contarry winds, they were unable to proceed toward Alexandria. At anchor in the harbour off Lochias, the Egyptian fleet posed an additional problem for the Roman ships. However, in a surprise attack, Caesar's soldiers set fire to the Egyptian ships, and the flames, spreading rapidly in the driving wind, consumed most of the dockyard, many structures near the palace, and also several thousand books that were housed in one of the buildings. From this incident, historians mistakingly assumed that the Great Library of Alexandria had been destroyed, but the Library was nowhere near the docks. | ” |

| “ | The most immediate damage occurred in the area around the docks, in shipyards, arsenals, and warehouses in which grain and books were stored. Some 40,000 book scrolls were destroyed in the fire. Not at all connected with the Great Library, they were account books and ledgers containing records of Alexandria's export goods bound for Rome and other cities throughout the world. | ” |

However, 25 years after the claimed burning of the library by Caesar, Strabo saw the Library and worked in it. In 25 BC Strabo used books located in the Library of Alexandria as sources and references for his book Geography. Another point used to refute the claim that the library was burned by Caesar is that Cicero, the most famous of all historians of the Roman Empire and who was well known for his hatred of Julius Caesar, never mentioned in his most renowned book Philippics that Caesar burned the Library. This in itself constitutes one more proof of Caesar’s innocence of this accusation

Therefore, it is most probable that the Royal Alexandrian Library was burned after Strabo’s visit to the city (25 BC) but before the beginning of the second century AD; otherwise these historians would not have mentioned the incident and mistakenly attributed it to Julius Caesar. It is also most probable that the Library was destroyed by someone other than Caesar, although the later generations linked the fire that took place in Alexandria during Caesar’s time to the burning of the Bibliotheca. Some believe that the most likely scenario was the destruction that accompanied the wars between Zenobia of Palmyra and the Roman Emperor Aurelian, in the second half of the 3rd century (see below).

It must be noted however that the Royal Alexandrian Library, or the Museum as it was called for including the original versions of the world’s most renowned books, was not the only library located in the city. There were at least two other libraries in Alexandria: the library of the Serapeum Temple and the library of the Cesarion Temple. The continuity of the literal and scientific life in Alexandria after the destruction of the Royal Library, as well as the flourishing of the city as the world’s centre for sciences and literature between the first and the sixth centuries AD, depended to a large extent on the presence of these two libraries and the books and references they contained. Thus, while it is historically recorded that the Royal Library was a private one for the royal family as well as for scientists and researchers, the libraries of the Serapeum and Cesarion temples were public libraries accessible to the people.

Furthermore, while the Royal Library was founded by Ptolemy II Philadelphus in the royal quarters of Bruchion near the palaces and the royal gardens, it was his son Ptolemy III who founded the Serapeum temple and its adjoined library in the popular quarters of Rhakotis. Later, the Serapeum library became known as the Daughter Library, because it contained copies of the original versions found in the Royal Library.

The exact extent of the damage to the library is unknown, as contemporary historians did not dare publish details devastating to a literate bibliophile such as Caesar, during his lifetime. As a point of context, library fires were common and replacement of handwritten manuscripts was extremely difficult, expensive and time-consuming. And after the long and expensive Alexandrian War there were fewer if any funds for the reconstruction and restocking of the library-- especially as it was now under the control of Rome whose citizens were not about to substantiate funds for an Egyptian library especially as Caesar was, arguably in memoriam, building his own in Rome.

The next account we have is Strabo's Geographia in 28bce, who does not mention the library specifically, but does mention-- among other details-- that he is not able to find a map in the city that he was on an earlier trip to Alex, pre-fire. Some scholars have used this account to suggest that from this we may infer the library was decimated to its foundations and collection destroyed (Abbadi). Certainty in this conclusion is shaken when one considers the context. The adjacent Museion was, according to the same account, in full-functioning condition-- which complicates the assumption that one building could be perfectly fine and the other fully destroyed. Also, we do know that at this time the Daughter Library at the Sarapeum was thriving and untouched by the fire, and as he does not mention that by name we can assert that for Strabo omission does not necessarily denote absence. Finally, as aforementioned, he confirms the life of the "Museion" of which the Great Library was the royal collection-- and in his other mentions of the Sarapeum and Museion he and other historians are inconsistent in their inference of the entire compound or the temple buildings specifically. So we may not infer that by mentioning the father institute of the Museion, but not the library arm specifically, that it is by any means confidently demolished. Finally, as one of the world's leading Geographers it is entirely possible that in the 20 plus years since his last visit to the library, the map he was referencing-- quite possibly a rare esoteric map considering his expertise and the vast collection of the library--that might have been either part of the library that was partially destroyed, or just simply a victim of twenty years of wear, tear and disrepair in a library who no longer has the inexhaustible funds it once did to re-copy and preserve its collection.

Attack of Aurelian, third century

The Library seems to have been maintained and continued in existence until its contents were largely lost during the taking of the city by the Emperor Aurelian (270–275), who was suppressing a revolt by Queen Zenobia of Palmyra. The smaller library located at the Serapeum survived, but part of its contents may have been taken to Constantinople to adorn the new capital in the course of the fourth century. However, Ammianus Marcellinus, writing around 378 AD seems to speak of the library in the Serapeum temple as a thing of the past, and he states that many of the Serapeum library's volumes were burnt when Caesar sacked Alexandria. As he says in Book 22.16.12-13:

| “ | Besides this there are many lofty temples, and especially one to Serapis, which, although no words can adequately describe it, we may yet say, from its splendid halls supported by pillars, and its beautiful statues and other embellishments, is so superbly decorated, that next to the Capitol, of which the ever-venerable Rome boasts, the whole world has nothing worthier of admiration. In it were libraries of inestimable value; and the concurrent testimony of ancient records affirm that 70,000 volumes, which had been collected by the anxious care of the Ptolemies, were burnt in the Alexandrian war when the city was sacked in the time of Caesar the Dictator. | ” |

While Ammianus Marcellinus may be simply reiterating Plutarch's tradition about Caesar's destruction of the library, it is possible that his statement reflects his own empirical knowledge that the Serapeum library collection had either been seriously depleted or was no longer in existence in his own day.

Decree of Theophilus in 391

In 391, Christian Emperor Theodosius I ordered the destruction of all pagan temples, and the Christian Patriarch Theophilus of Alexandria complied with this request.

Socrates Scholasticus provides the following account of the destruction of the temples in Alexandria in the fifth book of his Historia Ecclesiastica, written around 440:

| “ | At the solicitation of Theophilus, Bishop of Alexandria, the Emperor issued an order at this time for the demolition of the heathen temples in that city; commanding also that it should be put in execution under the direction of Theophilus. Seizing this opportunity, Theophilus exerted himself to the utmost to expose the pagan mysteries to contempt. And to begin with, he caused the Mithreum to be cleaned out, and exhibited to public view the tokens of its bloody mysteries. Then he destroyed the Serapeum, and the bloody rites of the Mithreum he publicly caricatured; the Serapeum also he showed full of extravagant superstitions, and he had the phalli of Priapus carried through the midst of the forum. Thus this disturbance having been terminated, the governor of Alexandria, and the commander-in-chief of the troops in Egypt, assisted Theophilus in demolishing the heathen temples. | ” |

The Serapeum once housed part of the Library, but it is not known how many, if any, books were contained in it at the time of destruction. Notably, the passage by Socrates Scholasticus, unlike that of Ammianus Marcellinus, makes no clear reference to a library or library contents being destroyed, only to religious objects being destroyed. The pagan author Eunapius of Sardis witnessed the demolition, and though he detested Christians, and was a scholar, his account of the Serapeum's destruction makes no mention of any library. Paulus Orosius admitted in the sixth book of his History against the pagans:

| “ | Today there exist in temples book chests which we ourselves have seen, and, when these temples were plundered, these, we are told, were emptied by our own men in our time, which, indeed, is a true statement. | ” |

However Orosius is not here discussing the Serapeum, nor is it clear who "our own men" are (the phrase may mean no more than "men of our time," since we know from contemporary sources that pagans also occasionally plundered temples).

As for the Museum, Mostafa El-Abbadi writes in Life and Fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria (Paris 1992):

| “ | The Mouseion, being at the same time a 'shrine of the Muses', enjoyed a degree of sanctity as long as other pagan temples remained unmolested. Synesius of Cyrene, who studied under Hypatia at the end of the fourth century, saw the Mouseion and described the images of the philosophers in it. We have no later reference to its existence in the fifth century. As Theon, the distinguished mathematician and father of Hypatia, herself a renowned scholar, was the last recorded scholar-member (c. 380), it is likely that the Mouseion did not long survive the promulgation of Theodosius' decree in 391 to destroy all pagan temples in the City. | ” |

John Julius Norwich, in his work Byzantium: The Early Centuries, places the destruction of the library's collection during the anti- Arian riots in Alexandria that transpired after the imperial decree of 391 (p.314).

Muslim conquest in 642

Several historians told varying accounts of a Muslim army led by Amr ibn al 'Aas sacking the city in 642 after the Byzantine army was defeated at the Battle of Heliopolis, and that the commander asked the caliph Umar what to do with the library. He gave the famous answer: "They will either contradict the Koran, in which case they are heresy, or they will agree with it, so they are superfluous." The Arabs subsequently burned the books to heat bathwater for the soldiers. It was also said that the Library's collection was still substantial enough at this late date to provide six months' worth of fuel for the baths. However, this account has been dismissed by some as a legend. While the first Western account of the supposed event was in Edward Pococke's 1663 translation of History of the Dynasties, it was dismissed as a hoax or propaganda as early as 1713 by Fr. Eusèbe Renaudot. Over the centuries, numerous succeeding scholars have agreed with Fr. Renaudot's conclusion, including Alfred J. Butler, Victor Chauvin, Paul Casanova and Eugenio Griffini. More recently, in 1990, noted Middle East scholar Bernard Lewis argued that the original account is not true, but that it survived over time because it was a useful myth for the great Twelfth century Muslim leader Saladin, who found it necessary to break up the Fatimid caliphate's collection of heretical Isma'ili texts in Cairo following his restoration of Sunnism to Egypt. Lewis proposes that the story of the caliph Umar's support of a library's destruction may have made Saladin's actions seem more acceptable to his people.

Conclusion

Although the actual circumstances and timing of the physical destruction of the Library remain uncertain, it is however clear that by the Eighth century A.D., the Library was no longer a significant institution and had ceased to function in any important capacity.

In fiction

The Library has been featured in numerous works of fiction over the millennia, in various forms of media. Notable recent instances include:

- Clive Cussler's adventure novel Treasure.

- The computer game Tomb Raider: The Last Revelation, all of which involve the survival of at least parts of the Library's catalog of texts.

- Scrolls from the Library are part of the lost treasure recovered in the 2004 movie National Treasure.

- All five computer games of Sid Meier's Civilization series includes the Library as a buildable Wonder of the World. In two of the games, its act is to acquire technologies that have been discovered from two or more other civilizations.

- In the city building game Pharaoh by Impressions Games, in a mission of the 'Cleopatra' expansion, the Library of Alexandria is built as a monument.

- The burning of the Library by Julius Caesar's forces is featured in the 1963 epic film Cleopatra.

- Author Steve Berry's novel The Alexandria Link features a modern day hunt for the resting place of the fabled institution.

- Author Conn Iggulden's novel The Gods of War, last of the Emperor Series, where it is said that Julius Caesar accidentally sets the library alight as he attempts to scuttle his ships to block the nearby port as a diversionary and defensive tactic.

- Author Jonathan Stroud's series The Bartimaeus Trilogy, refers to the Library in the third book, Ptolemy's Gate, in the djinn Bartimaues' narration of Egypt in 124 BC.

- In the show seaQuest DSV Season 1 Episode 4, Captain Bridger and crew discover the receiving building for the ancient library underwater.