Māori people

About this schools Wikipedia selection

SOS Children produced this website for schools as well as this video website about Africa. SOS Child sponsorship is cool!

| Prominent Māori, l. to r., top to bottom: Hone Heke and wife • Hinepare of Ngāti Kahungunu • Tukukino • Te Rangi Hīroa • Meri Te Tai Mangakahia • Apirana Ngata • Keisha Castle-Hughes • Winston Peters • Stephen Kearney | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| approx. 750,000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Māori, English |

||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Christianity, Māori religions |

||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||

|

other Polynesian peoples, |

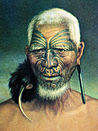

The Māori (Māori pronunciation: [ˈmaːɔɾi], / ˈ m ɑː ʊər i /) are the indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand. The Māori originated with settlers from eastern Polynesia, who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages at some time between 1250 and 1300 CE. Over several centuries in isolation, the Polynesian settlers developed a unique culture that became known as the "Māori", with their own language, a rich mythology, distinctive crafts and performing arts. Early Māori formed tribal groups, based on eastern Polynesian social customs and organisation. Horticulture flourished using plants they introduced, and later a prominent warrior culture emerged.

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand starting from the 17th century brought enormous change to the Māori way of life. Māori people gradually adopted many aspects of Western society and culture. Initial relations between Māori and Europeans were largely amicable, and with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 the two cultures coexisted as part of a new British colony. Rising tensions over disputed land sales led to conflict in the 1860s. Social upheaval, decades of conflict and epidemics of introduced disease took a devastating toll on the Māori population, which went into a dramatic decline. But by the start of the 20th century the Māori population had begun to recover, and efforts were made to increase their standing in wider New Zealand society. Traditional Māori culture has enjoyed a revival, and a protest movement emerged in the 1960s advocating Māori issues.

In the 2006 census, there were an estimated 620,000 Māori in New Zealand, making up roughly 15% of the national population. They are the second-largest ethnic group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders (" Pākehā"). In addition there are over 120,000 Māori living in Australia. The Māori language (known as Te Reo Māori) is spoken to some extent by about a quarter of all Māori, and 4% of the total population, although many New Zealanders regularly use Māori words and expressions, such as " kia ora", in normal speech. Māori are active in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, with independent representation in areas such as media, politics and sport.

Disproportionate numbers of Māori face significant economic and social obstacles, with lower life expectancies and incomes compared with other New Zealand ethnic groups, in addition to higher levels of crime, health problems and educational under-achievement. Socioeconomic initiatives have been implemented aimed at closing the gap between Māori and other New Zealanders. Political redress for historical grievances is also ongoing.

Etymology

In the Māori language the word māori means "normal", "natural" or "ordinary". In legends and oral traditions, the word distinguished ordinary mortal human beings—tāngata māori—from deities and spirits (wairua); likewise wai māori denoted "fresh water" as opposed to salt water. There are cognate words in most Polynesian languages, all deriving from Proto-Polynesian *ma(a)qoli, which has the reconstructed meaning "true, real, genuine".

Naming and self-naming

Early visitors from Europe to New Zealand generally referred to the inhabitants as "New Zealanders" or as "natives", but Māori became the term used by Māori to describe themselves in a pan-tribal sense.

Māori people often use the term tangata whenua (literally, "people of the land") to describe themselves in a way that emphasises their relationship with a particular area of land – a tribe may be the tangata whenua in one area, but not in another. The term can also refer to Māori as a whole in relation to New Zealand (Aotearoa) as a whole.

The Maori Purposes Act of 1947 required the use of the term "Maori" rather than "Native" in official usage, and the Department of Native Affairs became the Department of Māori Affairs. It is now Te Puni Kōkiri, or the Ministry for Māori Development.

Before 1974 ancestry determined the legal definition of "a Māori person". For example, bloodlines determined whether a person should enrol on the general electoral roll or the separate Māori. In 1947 the authorities determined that one man, five-eighths Māori, had improperly voted in the general parliamentary electorate of Raglan. The Māori Affairs Amendment Act 1974 changed the definition to one of cultural self-identification. In matters involving money (for example scholarships or Waitangi Tribunal settlements), authorities generally require some demonstration of ancestry or cultural connection, but no minimum "blood" requirement exists.

History

Origins

The most current reliable evidence strongly indicates that initial settlement of New Zealand occurred around 1280 CE at the end of the medieval warm period. Previous dating of some Kiore (Polynesian rat) bones at 50–150 CE has now been shown to have been unreliable; new samples of bone (and now also of unequivocally rat-gnawed woody seed cases) match the 1280 date of the earliest archaeological sites and the beginning of sustained deforestation by humans.

Māori oral history describes the arrival of ancestors from Hawaiki (the mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia), in large ocean-going waka. Migration accounts vary among tribes ( iwi), whose members may identify with several waka in their genealogies ( whakapapa). There is limited evidence of return, or attempted return voyages, from archaeological evidence in the Kermadec Islands.

No credible evidence exists of human settlement in New Zealand before the Polynesian voyagers. Compelling evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers came from east Polynesia and became the Māori. Language evolution studies and mitochondrial DNA evidence suggest that most Pacific populations originated from Taiwanese aborigines around 5,200 years ago (suggesting before migration from the Asian or Chinese mainland), moving down through Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

Archaic period (1280-1500)

The earliest period of Māori settlement is known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land with abundant birdlife, including several now extinct moa species weighing from 20 to 250 kilograms (40 to 550 lb). Other species, also now extinct, included a swan, a goose and the giant Haast's Eagle, which preyed upon the moa. Marine mammals, in particular seals, thronged the coasts, with coastal colonies much further north than today. At the Waitaki river mouth huge numbers of Moa bones estimated at 29,000 to 90,000 birds have been located. Further South, at the Shag River mouth at least 6,000 moa were slaughtered over a relatively short period.

Archaeology has shown that the Otago Region was the node of Māori cultural development during this time, and the majority of archaic settlements were on or within 10 km (6 mi) of the coast, though it was common to establish small temporary camps far inland. Settlements ranged in size from 40 people (e.g., Palliser Bay in Wellington) to 300–400 people, with 40 buildings (e.g., Shag River (Waihemo)). The best known and most extensively studied Archaic site is at Wairau Bar in the South Island. The site is similar to eastern Polynesian nucleated villages. Radio carbon dating shows it was occupied from about 1288 to 1300. Due to tectonic forces, some of the Wairau Bar site is now underwater. Work on the Wairau Bar skeletons in 2010 showed that life expectancy was very short. The oldest skeleton being 39 and most people dying in their 20s. Most of the adults showed signs of dietary or infection stress. Anaemia and arthritis were common. Infections such as TB may have been present as the symptoms were present in several skeletons. On average the adults were taller than other South Pacific people at 175 for males and 161 for females.

The Archaic period is remarkable for the lack of weapons and fortifications so typical of the later "Classic" Māori, and for its distinctive "reel necklaces". From this period onward around 32 species of birds became extinct, either through over-predation by humans and the kiore and kurī they introduced, repeated burning of the grassland, or climate cooling, which appears to have occurred from about 1400–1450. Early Māori enjoyed a rich, varied diet of birds, fish, seals and shellfish. Moa were also an important source of meat, and the various species were probably wiped out within 100 years according to Professor Allan Cooper.

Work by Helen Leach shows that Māori were using about 36 different food plants, though many required detoxification and long periods (12–24 hours) of cooking. D. Sutton's research on early Māori fertility found that first pregnancy occurred at about 20 years and the mean number of births was low, compared with other neolithic societies. The low number of births may have been due to the very low average life expectancy of 31–32 years. Analysis of skeletons at Wairau bar showed signs of a hard life with many having broken bones that had healed, suggesting a balanced diet and a supportive community that had the resources to support severely injured family members.

Classic period (1500-1642)

The cooling of the climate, confirmed by a detailed tree ring study near Hokitika, shows a significant, sudden and long-lasting cooler period from 1500. This coincided with a series of massive earthquakes in the South Island Alpine fault, a major earthquake in 1460 in the Wellington area, tsunamis that destroyed many coastal settlements, and the extinction of the moa and other food species. These were likely factors that led to sweeping changes to the Māori culture, which developed into the most well-known "Classic" period that was in place when European contact was made.

This period is characterised by finely made pounamu weapons and ornaments, elaborately carved canoes – a tradition that was later extended to and continued in elaborately carved meeting houses ( wharenui), and a fierce warrior culture, with fortified hillforts known as pā, frequent cannibalism and some of the largest war canoes ever built.

Around 1500 CE a group of Māori migrated east to the Chatham Islands, where, by adapting to the local climate and the availability of resources, they developed a culture known as the " Moriori" – related to but distinct from Māori culture in mainland New Zealand. A notable feature of the Moriori culture, an emphasis on pacifism, proved disastrous when a party of invading North Taranaki Māori arrived in 1835. Few of the estimated Moriori population of 2,000 survived.

The largest battle ever fought in New Zealand, the Battle of Hingakaka occurred around 1780–90, south of Ohaupo on a ridge near Lake Ngaroto. The battle was fought between about 7,000 warriors from a Taranaki-led force and a much smaller Waikato force under the leadership of Te Rauangaanga.

Early European contact (1642-1840)

European settlement of New Zealand occurred in relatively recent historical times. New Zealand historian Michael King in The Penguin History Of New Zealand describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world." Early European explorers, including Abel Tasman (who arrived in 1642) and Captain James Cook (who first visited in 1769), recorded their impressions of Māori. Initial contact between Māori and Europeans proved problematic, sometimes fatal, with several accounts of Europeans being cannibalised.

From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American sealers and whalers; some Māori crewed on the foreign ships with many crewing on whaling and sealing ships in New Zealand waters. Some of the South Island crews were almost totally Maori. Between 1800 and 1820 there were 65 sealing voyages and 106 whaling voyages to New Zealand, mainly from Britain and Australia. A trickle of escaped convicts from Australia and deserters from visiting ships, as well as early Christian missionaries, also exposed the indigenous population to outside influences. In the Boyd Massacre in 1809, Māori took hostage and killed 66 members of the crew and passengers in apparent revenge for the whipping of the son of a Māori chief by the captain. There were accounts of cannibalism, and this episode caused shipping companies and missionaries to be wary, and significantly reduced contact between Europeans and Māori for several years.

Early missionaries such as Kendal, Turner, Maunsel, Wade and the trader Polack, noted that the Maori population had a marked male/female differential. This was confirmed by an early census and several regional counts. It was caused by the customary practice of female infanticide. Female babies were often killed at birth by the mother by suffocation, strangulation or brain trauma. The reasons provided by Maori for this action were; that women were no use in war, the mother could not raise more than a few children and the mother is too weak to work. Infanticide is sometimes identified as a significant cause of depopulation. Bishop Selwyn who travelled widely in New Zealand said this was common throughout the country. Males made up about 60 to 75% of Maori, depending on the region. The 1858 census gave Maori population as 31,667 males and 24,303 females, confirming that the earlier imbalance persisted for many years. Maori suicide was also a custom that deeply concerned missionaries. In some areas it was the normal custom for a husband or wife to suicide when their partner died. By 1830, estimates placed the number of Europeans living among the Māori as high as 2,000. In 1838 there were 1,800 to 2,000 British subjects permanently in New Zealand of which 158 were runaway convicts or seamen. In addition there were about itinerant 1000 whalers either visiting or running temporary shore stations. The runaways had varying status-levels within Māori society, ranging from slaves to high-ranking advisors. Some runaways remained little more than prisoners, while others abandoned European culture and identified as Māori. These Europeans " gone native" became known as Pākehā Māori. Many Māori valued them as a means to the acquisition of European knowledge and technology, particularly firearms. When Pomare led a war-party against Titore in 1838, he had 131 Europeans among his warriors. Frederick Edward Maning, an early settler, wrote two lively accounts of life in these times, which have become classics of New Zealand literature: Old New Zealand and History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke.

Maori first learnt about formal schooling in Parramatta from 1809 where Samuel Marsden had a large farm and facilities for Maori to stay. He quickly made translation sheets for Europeans to use. Most of the Maori who stayed with him were Rangatira or sons. Marsden quickly learnt that his pupils were quick witted and loved verbal debate. The Maori language was first written down by Thomas Kendall in 1815 followed 5 years later by A Grammar and Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language, compiled by Professor Samuel Lee helped by Kendall, Waikato and Hongi Hika, on a visit to England in 1820. Progress in learning literacy was slow amongst Northern Maori as pupils were often taken out of school to do other things. At times the boys from 6-9 were taken out to go on war expeditions. The first known, independent letter was written in late 1825 by Hongi, a 10 year old orphan boy from Kerikeri. The letter was in Maori. Between February 1835 and January 1840 William Colenso printed 74,000 Maori language booklets from his press at Pahia. Two new words had to be invented as there was no Maori equivalent, hope and law. From 1843 the government distributed free gazettes to Maori called Ko Te Karere O Nui Tireni. It contained information about law, crimes, explanations and remarks about European customs. In 1844 the chiefs Waikato and Manakau urged the governor to establish English style schools. In 1847 a variety of schools were set up to teach English, Christianity, arithmetic and industrial training. Tauranga had a school with 100 pupils. In 1850 St. Stephens girls school was set up in Auckland. In 1858 a grant of 7,000 pounds given to set up a more wide ranging native education system under the Native Schools Act. English language use increased in Maori districts. By 1871 Maori MP Karaitaina Tokomoana pushed for more use of English in schools, as missionary schools were still teaching in Maori. He wanted Maori to be taught in English only. In 1897 Samuel Williams estimated that 90% of Maori adults could either read or write.

During the period from 1805 to 1840 the acquisition of muskets by tribes in close contact with European visitors upset the balance of power among Māori tribes, leading to a period of bloody inter-tribal warfare, known as the Musket Wars, which resulted in the decimation of several tribes and the driving of others from their traditional territory. During the Musket wars the Maori population it has been estimated that the total number dropped from about 100,000 in 1800 to between 50,000 and 80,000 at the end of the wars in 1843. The 1856-57 census of Maori which gives a figure of 56,049 suggests the lower number of around 50,000 is perhaps more accurate, as the 1850s was a decade of relative stability and Maori economic growth. The picture is confused by uncertainty over how or if Pakeha Maori were counted and the severe dislocation of many of the less powerful iwi and hapu during the wars. The smashing of normal society by the four decade wars and the driving of peaceful tribes from their productive turangawaiwai, such as the Moriori in the Chatham Islands by invading forces from North Taranaki, had a catastrophic effect on these defeated tribes. European diseases such as influenza and measles killed an unknown number of Māori: estimates vary between ten and fifty percent. Epidemics had occurred before the arrival of Europeans according to information given by Maori to missionaries in 1839. The missionary Ashwell mentioned that a type of typus was responsible for many deaths around Pahia. He and other missionaries were concerned that poor native housing and a lack of hygiene, especially the failure to wash themselves or clothing, were major contributing factors. Venereal disease was also common. Missonaries were horrified by the regular prostitution of girls as young as 8 or 10. Apirana Ngata said that prostition was notorious and lead to sterility amongst those practicing early prostitution. Epidemics were made far worse by the lack of food especially in winter. Missionaries noted that the death rate for children 5-14, was far higher than for adults East coast Maori suffered similar epidemics even though there was almost no contact with Europeans. Although the period of deaths by epidemic appears to be associated more with the later 1800s. Spread of epidemics was caused by a huge influx of European settlers in the 1870s who in many cases did not have rigorous heath checks.700 poor Scandinavian settlers who settled around Norsewood in the 1870s suffered horrendous death rates although they had almost no contact with Maori.Unlike Maori, the overall fecundity of the Scandinavians was not effected. The late 1870s saw the beginning of the Long Depression which lasted until the mid-1880s. This caused widespread hardship among Maori and the new migrants. Maori became keen sellers of land in this period .The long lasting hui associated with the land court process helped to spread infection from hapu to hapu as did the many inter hapu hui celebrations following court room success as triumphant hapu sought to expand their mana by having elaborate feasts.

Te Rangi Hīroa documents an epidemic caused by a respiratory disease that Māori called rewharewha. It "decimated" populations in the early 19th Century and "spread with extraordinary virulence throughout the North Island and even to the South..." He also says, p83: "Measles, typhoid, scarlet fever, whooping cough and almost everything, except plague and sleeping sickness, have taken their toll of Maori dead." Economic changes also took a toll: migration into unhealthy swamplands to produce and export flax led to further mortality.

British Treaty with the people of New Zealand

With increasing Christian missionary activity and growing European settlement in the 1830s, and with growing lawlessness in New Zealand, the British Crown acceded to repeated requests from missionaires and some chiefs to intervene. Some freewheeling escaped convicts and seamen, as well as gunrunners and Americans actively worked against the British government by spreading rumours amongst Maori that the government would oppress and mistreat them. Tamati Waka Nene a pro government chief was angry that the government had not taken active steps to stop gunrunners selling weapons to rebels in Hokianga. As well, the French were showing imminent interest in acquiring New Zealand for Paris.It was believed that the French catholic missionaries were spreading anti British feeling. All of the chiefs who spoke against the Treaty on 5 February 1840 were catholic.Years after the treaty was signed Pompallier admitted that all the catholic chiefs and especially Rewa, had consulted him for advice. Ultimately, Queen Victoria sent Royal Navy Captain William Hobson with instructions to negotiate a treaty between Britain and the people of New Zealand.

Soon after arrival in New Zealand in February 1840, Hobson negotiated a treaty with North Island chiefs, later to become known as the Treaty of Waitangi. In the end, 500 tribal chiefs and a small number of Europeans signed the Treaty, while some chiefs — such as Te Wherowhero in Waikato, and Te Kani-a-Takirau from the east coast of the North Island — refused to sign. The Treaty gave Māori the rights of British subjects and guaranteed Māori property rights and tribal autonomy, in return for accepting British governance and sovereignty.

Considerable dispute continues over aspects of the Treaty of Waitangi. The original treaty written mainly by Busby and translated into Maori by Henry Williams who was moderately proficient in Maori and his son William who was more skilled. They were handicapped by their imperfect Maori and the lack of exactly similar words in Maori(there was no word for "law" in Maori) . At Waitangi the chiefs signed the Maori translation. Several versions of the English text exist, as Hobson ordered multiple copies to be produced. At least 200 and up to 400 hand written copies were made, some of which were sent to England and Canada. The situation became complicated because more Maori chiefs than had been anticipated wanted to sign, and literally no more space on the Maori text version was left. As well food was running out at the signing, and the chiefs simply wanted the signing over so they could return with the good news to their tribal groups. Those present endorsed their signatures onto whatever incidentally-connected paper was available - and some of these signatures were collected on unofficial texts. This has led to considerable debate in recent years of the late 20th Century and early 21st Century at to what the Treaty means. R. Bennett.Treaty to Treaty .2007

Despite the different understandings of the treaty, relations between Māori and Europeans during the early colonial period were largely peaceful. Many Māori groups set up substantial businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets. Among the early European settlers who learnt the Māori language and recorded Māori mythology, George Grey, Governor of New Zealand from 1845–1855 and 1861–1868, stands out.

However, rising tensions over disputed land purchases and attempts by Māori in the Waikato to establish what some saw as a rival to the British system of royalty led to the New Zealand wars in the 1860s. These conflicts started when rebel Maori attacked isolated settlers in Taranaki but were fought mainly between Crown troops –from both Britain and new regiments raised in Australia, aided by settlers and some allied Māori (known as kupapa) – and numerous Māori groups opposed to the disputed land sales including some Waikato Maori.

While these conflicts resulted in few Māori (compared to the earlier Musket wars) or European deaths, the colonial government confiscated tracts of tribal land as punishment for what were called rebellions, in some cases taking land from tribes that had taken no part in the war, although this was almost immediately returned. Some of the confiscated land was returned to both kupapa and "rebel" Māori. Several minor conflicts also arose after the wars, including the incident at Parihaka in 1881 and the Dog Tax War from 1897–98.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 established the Native Land Court, which had the purpose of transferring Māori land from communal ownership into individual title. Māori land under individual title became available to be sold to the colonial government or to settlers in private sales. Between 1840 and 1890 Māori sold 95 percent of their land (63,000,000 of 66,000,000 acres (270,000 km2) in 1890). In total 4% of this was confiscated land, although about a quarter of this was returned. 300,000 acres was also returned to Kupapa Maori mainly in the lower Waikato River Basin area. Individual Māori titleholders received considerable capital from these land sales, with some lower Waikato Chiefs being given a 1000 pounds each. Disputes later arose over whether or not promised compensation in some sales was fully delivered. Some claim that later, the selling off of Maori land and the lack of appropriate skills hampered Māori participation in growing the New Zealand economy, eventually diminishing the capacity of many Maori to sustain themselves. The Maori MP Henare Kaihau, from Waiuku, who was executive head of the King Movement worked alongside King Mahuta to sell land to the government. At that time the king sold 185,000 acres per year. In 1910 the Maori Land Conference at Waihi discussed selling a further 600,000 acres. King Mahuta had been successful in getting restitution for some blocks of land previously confiscated and these were returned to the King in his name. Henare Kaihau invested all the money- 50,000 pounds- in an Auckland land company which collapsed and all 50,000 pounds of the kingitanga money was lost.

In 1884 King Tāwhiao withdrew money from the kingitanga bank, Te Peeke o Aotearoa to travel to London to see Queen Victoria to try and persuade her to honour the Treaty between their peoples. However he did not get beyond the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who said it was a New Zealand problem. Returning to New Zealand the Premier, Robert Stout, insisted that all events happening before 1863 were the responsibility of the Imperial Government.

By 1891 Maori comprised just 10% of the population but still owned 17% of the land, although much of it was of poor quality.

Decline and revival

By the late 19th century a widespread belief existed amongst both Pākehā and Māori that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture and become assimilated into the European population. In 1840, New Zealand had a Māori population of about 50,000 to 70,000 and only about 2,000 Europeans. By 1860 it was estimated at 50,000. The Māori population had declined to 37,520 in the 1871 census, although Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck) believed this figure was too low. The figure was 42,113 in the 1896 census, by which time Europeans numbered more than 700,000. Professor Ian Poole noticed that as late as 1890 40% of all female children were dead before they were one, a much higher rate than for males.

The decline of the Māori population did not continue, and levels recovered. By 1936 the Māori figure was 82,326, although the sudden rise in the 1930s was probably due to the introduction of the family benefit − only payable when a birth was registered, according to Professor Poole. Despite a substantial level of intermarriage between the Māori and European populations, many Māori retained their cultural identity. A number of discourses developed as to the meaning of "Māori" and to who counted as Māori or not.

The parliament instituted 4 Maori seats in 1867, giving all Maori men universal suffrage 12 years ahead of their European New Zealand counterparts - who until the 1879 general elections needed to be landowners. New Zealand was thus the first neo-European nation in the world to give the vote to its indigenous people, but while the seats did increase Māori participation in politics, the relative size of the Māori population of the time vis à vis Pākehā would have warranted approximately 15 seats, although Maori have the option of voting in either Maori or general electorates giving them a choice.

From the late 19th century, successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll, Apirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hīroa and Maui Pomare, showing skill in the arts of Pākehā politics; at one point Carroll became Acting Prime Minister. The group, known as the Young Māori Party, cut across voting-blocs in Parliament and aimed to revitalise the Māori people after the devastation of the previous century. For them this involved assimilation – Māori adopting European ways of life such as Western medicine and education, especially the learning of English. However, Ngata in particular also wished to preserve traditional Māori culture, especially the arts. Ngata acted as a major force behind the revival of arts such as kapa haka and carving. He also enacted a programme of land development which helped many iwi retain and develop their land. Ngata became very close to Te Puea the Waikato kingite leader who was supported by the government in her attempt to improve living conditions for Waikato. Ngata transferred four blocks of land to Te Puea and her husband and arranged extensive government grants and loans. Ngata sacked the pakeha farm development officer and replaced him with Te Puea. He then arranged for her to have car to travel around the various farms.Te Puea's husband was also given a large farm at Tikitere near Rotorua. The public, media and parliament became alarmed at the flow of funds from government to Te Puea during the recession. A Royal Commission was held in 1934 that found Ngata guilty of maladministration and misappropriation of funds to the value of 500,000 pounds. Ngata was forced to resign.

During World War One, a Maori pioneer force was taken to Egypt but quickly was turned into a successful combat infantry battalion and in the last years of the war was known as the Maori battalion. The battalion mainly comprised Arawa, Ngati Porou, NgaPuhi and later many Cook Islanders. The Waikato and Taranaki tribes refused to enlist or be conscripted, although the Maniapoto tribe, which had been at the heart of the 1863 Maori rebellion, supplied many soldiers. The leader of the Maori king movement during WW1, Te Puea, still harbouring grievances over their defeat and loss of land in 1863, worked covertly to undermine the government's attempts to unify Maori behind the war. Her brother was one of many Waikato conscripts arrested and jailed after refusing to serve their country. The actions of Te Puea lead to Waikato tribes being ostracized to some extent by the government after the war. Te Puea's stand caused huge difficulties for Waikato Maori MP Maui Pomare who was an avid supporter of Maori involvement in WW1.

Maori were badly hit by the 1918 influenza epidemic when the Maori battalion returned from the Western Front. The death rate from influenza for Maori was 4.5 times higher than for Pakeha. Many Maori -especially in the Waikato were very reluctant to visit a doctor and only went to a hospital when the patient was nearly dead. To cope with isolation increasingly Waikato Maori, under Te Puea's leadership, returned to the old Pai Marire (Hau hau) cult of the 1860s.

Until 1893,53 years after the Treaty of Waitangi, Maori did not contribute to the country's income by paying tax on land holdings at all. In 1893 a very light tax was payable only on leasehold land and it was not till 1917 that Maori were required to pay a heavier tax equal to half that paid by other New Zealanders.

During WW2 the government decided to exempt Māori from the conscription that applied to other citizens in World War II, but Māori volunteered in large numbers, forming the 28th or Māori Battalion, which performed creditably, notably in Crete, North Africa and Italy. Altogether 16,000 Māori took part in the war.3,600 served in the Maori Battalion,the remainder serving in artillery,pioneers, home guard,infantry,airforce and navy. 204,000 New Zealanders served during WW2. Maori, including Cook Islanders, made up 12% of the total force.

Many Māori migrated to larger rural towns and cities during the Depression and post-WWII periods in search of employment, leaving rural communities depleted and disconnecting many urban Māori from their traditional ways of life. Yet while standards of living improved among Māori during this time, they continued to lag behind Pākehā in areas such as health, income, skilled employment and access to higher levels of education. Māori leaders and government policymakers alike struggled to deal with social issues stemming from increased urban migration, including a shortage of housing and jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty and health problems.

Recent history

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a cultural revival concurrent with a protest movement. Government recognition of the growing political power of Māori and political activism have led to limited redress for confiscation of land and for the violation of other property rights. The Crown set up the Waitangi Tribunal, a body with the powers of a Commission of Enquiry, to investigate and make recommendations on such issues, but it cannot make binding rulings. Indeed, the Government need not accept the findings of the Waitangi Tribunal, and has rejected some of them.

Since 1976, people of Māori descent choose to enroll on either the general or Māori roll, and vote in either the Maori only or general electorates but not both. After the 1993 introduction of the MMP electoral system the number of electorates floats, meaning that the electoral population of a Māori seat, (there are currently seven), can remain roughly equivalent to that of a general seat.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the government negotiated with Māori to provide redress for breaches by the Crown of the guarantees set out in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. By 2006 the government had provided over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it in the form of land deals. The largest settlement, signed on 25 June 2008 with seven Māori iwi, transferred nine large tracts of forested land to Māori control. As a result of the redress paid to many iwi, Māori now have significant interests in the fishing and forestry industries. There is a growing Māori leadership who see the treaty settlements as a platform for economic development.

Despite a growing acceptance of Māori culture in wider New Zealand society, the settlements have courted controversy: some Māori have complained that the settlements occur at a level of between 1 and 2.5 cents on the dollar of the value of the confiscated lands; conversely, some non-Māori denounce the settlements and socioeconomic initiaves as amounting to race-based preferential treatment. Both of these sentiments were expressed during the New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy in 2004.

Culture

Traditional culture

The ancestors of the Māori arrived from eastern Polynesia during the 13th century, bringing with them Polynesian cultural customs and beliefs. Early European researchers, such as Julius von Haast, a geologist, incorrectly interpreted archaeological remains as belonging to a pre-Māori Paleolithic people; later researchers, notably Percy Smith, magnified such theories into an elaborate scenario with a series of sharply-defined cultural stages which had Māori arriving in a Great Fleet in 1350 CE and replacing the so-called "moa-hunter" culture with a "classical Māori" culture based on horticulture. The development of Māori material culture has been similarly delineated by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa into "cultural periods", from the earlier "Ngā Kakano" stage to the later "Te Tipunga" period, before the "Classic" period of Māori history.

However, the archaeological record indicates a gradual evolution of a neolithic culture that varied in pace and extent according to local resources and conditions. In the course of a few centuries, the growing population led to competition for resources and an increase in warfare. The archaeological record reveals an increased frequency of fortified pā, although debate continues about the amount of conflict. Various systems arose which aimed to conserve resources; most of these, such as tapu and rāhui, used religious or supernatural threats to discourage people from taking species at particular seasons or from specified areas.

Warfare between tribes was common, generally over land conflicts or to restore mana. Fighting was carried out between subtribes ( hapū). Although not practised during times of peace, Māori would sometimes eat their conquered enemies. Missionaries observed that slaves, especially female slaves, were killed at the whim of their masters, for minor misdemeanors. Chiefs jealously guarded their powers of authority and severely punished anyone who transgressed. Brutal punishment increased the mana of a chief. A chief was above any law. After 1800 chiefs found British law very strange in that even leaders were expected to obey its principles As Māori continued in geographic isolation, performing arts such as the haka developed from their Polynesian roots, as did carving and weaving. Regional dialects arose, with differences in vocabulary and in the pronunciation of some words.In 1819 2 young northern chiefs Tuai and Titere who had learnt to speak and write English went to London where they met the language expert Samuel Lee. They stayed with a school teacher Hall, who they told that even in Northern New Zealand there were "different languages and dialects". The language retained enough similarities to other Eastern Polynesian languages, to the point where a Tahitian chief on James Cook's first voyage in the region acted as an interpreter between Māori and the crew of the Endeavour.

Belief and religion

Traditional Māori beliefs have their origins in Polynesian culture. Many stories from Māori mythology are analogous with stories across the Pacific Ocean. Polynesian concepts such as tapu (sacred), noa (non-sacred), mana (authority/prestige) and wairua (spirit) governed everyday Māori living. These practices remained until the arrival of Europeans, when much of Māori religion and mythology was supplanted by Christianity. Today, Māori "tend to be followers of Presbyterianism, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons), or Māori Christian groups such as Rātana and Ringatū", but with Catholic, Anglican and Methodist groupings also prominent. There is also a very small community of Māori Muslims.

Performing arts

Kapa haka (literally "haka team") is a traditional Māori performance art, encompassing many forms, that is still popular today. It includes haka (posture dance), poi (dance accompanied by song and rhythmic movements of the poi, a light ball on a string), waiata-ā-ringa (action songs) and waiata koroua (traditional chants). From the early 20th century kapa haka concert parties began touring overseas.

Since 1972 there has been a regular competition, the Te Matatini National Festival, organised by the Aotearoa Traditional Māori Performing Arts Society. Māori from different regions send representative groups to compete in the biannual competition. There are also kapa haka groups in schools, tertiary institutions and workplaces. It is also performed at tourist venues across the country.

Sport

Māori participate fully in New Zealand's sporting culture. The national rugby union, rugby league and netball teams have featured many Māori players. There are also Māori rugby union, rugby league and cricket representative teams that play in international competitions. Ki-o-rahi and tapawai are two sports of Māori origin. Ki-o-rahi got an unexpected boost when McDonalds chose it to represent New Zealand. Waka ama (outrigger canoeing) is also popular with Māori.

Language

From about 1890, Maori MPs realised the importance of English literacy to Maori and insisted that all Maori children be taught in English. Missionaries, who still ran many Maori schools, had been teaching exclusively in Maori but the Maori MPs insisted this stop. However attendance at school for many Maori was intermittent.The Māori language, also known as te reo Māori (pronounced [ˈmaːoɾi, te ˈɾeo ˈmaːoɾi]) or simply te reo ("the language"), has the status of an official language. Linguists classify it within the Eastern Polynesian languages as being closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan and Tahitian; somewhat less closely to Hawaiian and Marquesan; and more distantly to the languages of Western Polynesia, including Samoan, Tokelauan, Niuean and Tongan. Before European contact Māori did not have a written language and "important information such as whakapapa was memorised and passed down verbally through the generations". Maori were familiar with the concept of maps and when interacting with missionaries in 1815 could draw accurate maps of their rohe, onto paper, that were the equal of European maps. Missionaries surmised that Maori had traditionally drawn maps on sand or other natural material.

In many areas of New Zealand, Māori lost its role as a living community language used by significant numbers of people in the post-war years. In tandem with calls for sovereignty and for the righting of social injustices from the 1970s onwards, New Zealand schools now teach Māori culture and language as an option, and pre-school kohanga reo ("language-nests") have started, which teach tamariki (young children) exclusively in Māori. These now extend right through secondary schools (kura tuarua). Most preschool centres teach basics such as colours, numerals and greetings in Maori songs and chants.

In 2004 Māori Television, a government-funded channel committed to broadcasting primarily in te reo, began. Māori is an official language de jure, but English is de facto the national language. At the 2006 Census, Māori was the second most widely-spoken language after English, with four percent of New Zealanders able to speak Māori to at least a conversational level. No official data has been gathered on fluency levels.

Society

Historical development

Polynesian settlers in New Zealand developed a distinct society over several hundred years. Social groups were tribal, with no unified society or single Māori identity until after the arrival of Europeans. Nevertheless, common elements could be found in all Māori groups in pre-European New Zealand, including a shared Polynesian heritage, a common basic language, familial associations, traditions of warfare, and similar mythologies and religious beliefs.

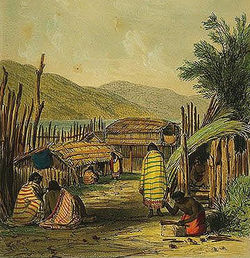

Most Māori lived in villages, which were inhabited by several whānau (extended families) who collectively formed a hapū (clan or subtribe). Members of a hapū cooperated with food production, gathering resources, raising families and defence. Māori society across New Zealand was broadly stratified into three classes of people: rangatira, chiefs and ruling families; tūtūā, commoners; and mōkai, slaves. Tohunga also held special standing in their communities as specialists of revered arts, skills and esoteric knowledge.

Shared ancestry, intermarriage and trade strengthened relationships between different groups. Many hapū with mutually-recognised shared ancestry formed iwi, or tribes, which were the largest social unit in Māori society. Hapū and iwi often united for expeditions to gather food and resources, or in times of conflict. In contrast, warfare developed as an integral part of traditional life, as different groups competed for food and resources, settled personal disputes, and sought to increase their prestige and authority.

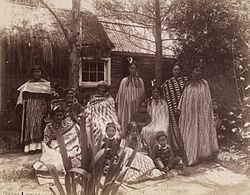

The arrival of Europeans to New Zealand dates back to the 17th century, although it was not until the expeditions of James Cook over a hundred years later that any meaningful interactions occurred between Europeans and Māori. For Māori, the new arrivals brought opportunities for trade, which many groups embraced eagerly. Early European settlers introduced tools, weapons, clothing and foods to Māori across New Zealand, in exchange for resources, land and labour. Māori began selectively adopting elements of Western society during the 19th century, including European clothing and food, and later Western education, religion and architecture.

But as the 19th century wore on, relations between European colonial settlers and different Māori groups became increasingly strained. Tensions led to conflict in the 1860s, and the confiscation of millions of acres of Māori land. Significant amounts of land were also purchased by the colonial government and later through the Native Land Court. The wholesale selling of land and the inexperience in fiscal management, coupled with low population growth and social dislocation drastically reduced the economic sustainability and social organisation of many hapū and iwi. The 19th century also saw an apparent decline in the Māori population across New Zealand, but this was most likely due to Maori not completing the census in the period 1863-1920s as the Maori population suddenly increased in the 1930s when the family benefit was introduced. The apparent drop in population was widely attributed to outbreaks of introduced disease, war, infanticide, poor housing conditions and lack of hygiene.

20th century

By the start of the 20th century, a greater awareness had emerged of a unified Māori identity, particularly in comparison to Pākehā, who now overwhelmingly outnumbered the Māori as a whole. Māori and Pākehā societies remained largely separate – socially, culturally, economically and geographically – for much of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The key reason for this was that Māori remained almost exclusively a rural population, whereas increasingly the European population was urban especially after 1900. Nevertheless, Māori groups continued to engage with the government and in legal processes to increase their standing in – and ultimately further their incorporation into – wider New Zealand society. The main point of contact with the government were the four Māori Members of Parliament.

Many Māori migrated to larger rural towns and cities during the Depression and post-WWII periods in search of employment, leaving rural communities depleted and disconnecting many urban Māori from their traditional social controls and tribal homelands. Yet while standards of living improved among Māori, they continued to lag behind Pākehā in areas such as health, income, skilled employment and access to higher levels of education. Māori leaders and government policymakers alike struggled to deal with social issues stemming from increased urban migration, including a shortage of housing and jobs, and a rise in urban crime, poverty and health problems.

In regards to housing, a 1961 census revealed significant differences in the living conditions of Māori and Europeans. That year, out of all the (unshared) non-Māori private dwellings in New Zealand, 96.8% had a bath or shower, 94.1% a hot water service, 88.7% a flush toilet, 81.6% a refrigerator, and 78.6% an electric washing machine. By contrast, for all (unshared) Māori private dwellings that same year, 76.8% had a bath or shower, 68.9% a hot water service, 55.8% a refrigerator, 54.1% a flush toilet, and 47% an electric washing machine.

While the arrival of Europeans had a profound impact on the Māori way of life, many aspects of traditional society have survived into the 21st century. Māori participate fully in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, leading largely Western lifestyles while also maintaining their own cultural and social customs. The traditional social strata of rangatira, tūtūā and mōkai have all but disappeared from Māori society, while the roles of tohunga and kaumātua are still present. Traditional kinship ties are also actively maintained, and the whānau in particular remains an integral part of Māori life.

Marae, hapū and iwi

Māori society at a local level is particularly visible at the marae. Formerly the central meeting spaces in traditional villages, marae today usually comprise a group of buildings around an open space, that frequently host events such as weddings, funerals, church services and other large gatherings, with traditional protocol and etiquette usually observed. They also serve as the base of one or sometimes several hapū.

Most Māori affiliate with one or more iwi (and hapū), based on genealogical descent ( whakapapa). Iwi vary in size, from a few hundred members to over 100,000 in the case of Ngāpuhi. Many people do not live in their traditional tribal regions as a result of urban migration.

Iwi are usually governed by rūnanga – governing councils or trust boards, which represent the iwi in consultations and negotiations with the New Zealand government. Rūnanga also manage tribal assets and spearhead health, education, economic and social initiatives to help iwi members.

Population

In the 2006 Census, 565,000 people identified as being part of the Māori ethnic group, accounting for 14.6% of the New Zealand population, while 644,000 people (17.7%) claimed Māori descent. As of 1 December 2011, the estimated Māori population in New Zealand was 672,400. Many Māori also have at least some Pākehā ancestry, resulting from a high rate of intermarriage between the two cultures.

According to the 2006 Census, the largest iwi by population is Ngāpuhi (122,000), followed by Ngāti Porou (72,000), Ngāti Kahungunu (60,000) and Ngāi Tahu (49,000). However, 102,000 Māori in the 2006 Census could not identify their iwi. Outside of New Zealand, a large Māori population exists in Australia, estimated at 126,000 in 2006. The Māori Party has suggested a special seat should be created in the New Zealand parliament representing Māori in Australia. Smaller communities also exist in the United Kingdom (approx. 8,000), the United States (up to 3,500) and Canada (approx. 1,000).

Socioeconomic challenges

Māori on average have fewer assets than the rest of the population, and run greater risks of many negative economic and social outcomes. Over 50% of Māori live in areas in the three highest deprivation deciles, compared with 24% of the rest of the population. Although Māori make up only 14% of the population, they make up almost 50% of the prison population.

Māori have higher unemployment-rates than other cultures resident in New Zealand Māori have higher numbers of suicides than non-Māori. "Only 47% of Māori school-leavers finish school with qualifications higher than NCEA Level One; compared to 74% European; 87% Asian." Although New Zealand rates well very globally in the PISA rankings that compare national performance in reading, science and maths "...once you disaggregate the PISA scores, Pakeha students are second in the world and Maori are 34th..." Māori suffer more health problems, including higher levels of alcohol and drug abuse, smoking and obesity. Less frequent use of healthcare services mean that late diagnosis and treatment intervention lead to higher levels of morbidity and mortality in many manageable conditions, such as cervical cancer, diabetes per head of population than non-Māori. Although Maori life expectancy rates have increased dramatically in the last 50 years, they still have considerably lower life-expectancies compared to New Zealanders of European ancestry: Māori males 69.0 years vs. non-Māori males 77.2 years; Māori females 73.2 yrs vs. non-Māori females 81.9 years. Also, a recent study by the New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse showed that Māori women and children are more likely to experience domestic violence than any other ethnic group.

Race relations

The status of Māori as the indigenous people of New Zealand is recognised in New Zealand law by the term tangata whenua (lit. "people of the land"), which identifies the traditional connection between Māori and a given area of land. Māori as a whole can be considered as tangata whenua of New Zealand entirely; individual iwi are recognised as tangata whenua for areas of New Zealand in which they are traditionally based, while hapū are tangata whenua within their marae. New Zealand law periodically requires consultation between the government and tangata whenua – for example, during major land development projects. This usually takes the form of negotiations between local or national government and the rūnanga of one or more relevant iwi, although the government generally decides which (if any) concerns are acted upon.

Māori issues are a prominent feature of race relations in New Zealand. Historically, many Pākehā viewed race relations in their country as being the "best in the world", a view that prevailed until Māori urban migration in the mid-20th century brought cultural and socioeconomic differences to wider attention.

Māori protest movements grew significantly in the 1960s and 1970s seeking redress for past grievances, particularly in regard to land rights. Successive governments have responded by enacting affirmative action programmes, funding cultural rejuvenation initiatives and negotiating tribal settlements for past breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi. Further efforts have focused on cultural preservation and reducing socioeconomic disparity.

Nevertheless, race relations remains a contentious issue in New Zealand society. Māori advocates continue to push for further redress claiming that their concerns are being marginalised or ignored. Conversely, critics denounce the scale of assistance given to Māori as amounting to preferential treatment for a select group of people based on race. Both sentiments were highlighted during the foreshore and seabed controversy in 2004, in which the New Zealand government claimed sole ownership of the New Zealand foreshore and seabed, over the objections of Māori groups who were seeking customary title.

Commerce

The New Zealand Law Commission has started a project to develop a legal framework for Māori who want to manage communal resources and responsibilities. The voluntary system proposes an alternative to existing companies, incorporations, and trusts in which tribes and hapū and other groupings can interact with the legal system. The foreshadowed legislation, under the proposed name of the "Waka Umanga (Māori Corporations) Act", would provide a model adaptable to suit the needs of individual iwi. At the end of 2009, the proposed legislation was awaiting a second hearing.

Wider commercial exposure has increased public awareness of the Māori culture, but has also resulted in several notable legal disputes. Between 1998 and 2006, Ngāti Toa attempted to trademark the haka " Ka Mate" to prevent its use by commercial organisations without their permission. In 2001, Danish toymaker Lego faced legal action by several Māori tribal groups (fronted by lawyer Maui Solomon) and members of the on-line discussion forum Aotearoa Cafe for trademarking Māori words used in naming the Bionicle product range – see Bionicle Māori controversy.

Political representation

Māori have been involved in New Zealand politics since the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand, before the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840. Māori have had reserved seats in the Parliament of New Zealand since 1868: presently, this accounts for seven of the 122 seats in New Zealand's unicameral parliament. The contesting of these seats was the first opportunity for many Māori to participate in New Zealand elections, although the elected Māori representatives initially struggled to assert significant influence. Māori received universal suffrage with other New Zealand citizens in 1893.

Being a traditionally tribal people, no one organisation ostensibly speaks for all Māori nationwide. The Māori King Movement originated in the 1860s as an attempt by several iwi to unify under one leader: in modern times, it serves a largely ceremonial role. Another attempt at political unity was the Kotahitanga Movement, which established a separate Māori Parliament that held annual sessions from 1892 until its last sitting in 1902.

There are seven designated Māori seats in the Parliament of New Zealand (and Māori can and do stand in and win general roll seats), and consideration of and consultation with Māori have become routine requirements for councils and government organisations. Debate occurs frequently as to the relevance and legitimacy of the Māori electoral roll, and the National Party announced in 2008 it would abolish the seats when all historic Treaty settlements have been resolved, which it aims to complete by 2014. Several Māori political parties have formed over the years to improve the position of Māori in New Zealand society. The present Māori Party, formed in 2004, secured 1.43% of the party vote at the 2011 general election and holds three seats in the 50th New Zealand Parliament, with two MPs serving as Ministers outside Cabinet.