Alzheimer's disease

Did you know...

SOS believes education gives a better chance in life to children in the developing world too. To compare sponsorship charities this is the best sponsorship link.

Alzheimer's disease (AD), also called Alzheimer disease, Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer Type (SDAT) or simply Alzheimer's, is the most common form of dementia. This incurable, degenerative, and terminal disease was first described by German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Alois Alzheimer in 1906 and was named after him. Generally it is diagnosed in people over 65 years of age, although the less-prevalent early-onset Alzheimer's can occur much earlier. An estimated 26.6 million people worldwide had Alzheimer's in 2006; this number may quadruple by 2050.

Although the course of Alzheimer's disease is unique for every individual, there are many common symptoms. The earliest observable symptoms are often mistakenly thought to be 'age-related' concerns, or manifestations of stress. In the early stages, the most commonly recognised symptom is memory loss, such as difficulty in remembering recently learned facts. When a doctor or physician has been notified, and AD is suspected, the diagnosis is usually confirmed with behavioural assessments and cognitive tests, often followed by a brain scan if available. As the disease advances, symptoms include confusion, irritability and aggression, mood swings, language breakdown, long-term memory loss, and the general withdrawal of the sufferer as their senses decline. Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death. Individual prognosis is difficult to assess, as the duration of the disease varies. AD develops for an indeterminate period of time before becoming fully apparent, and it can progress undiagnosed for years. The mean life expectancy following diagnosis is approximately seven years. Fewer than three percent of individuals live more than fourteen years after diagnosis.

The cause and progression of Alzheimer's disease are not well understood. Research indicates that the disease is associated with plaques and tangles in the brain. Currently used treatments offer a small symptomatic benefit; no treatments to delay or halt the progression of the disease are as yet available. As of 2008, more than 500 clinical trials were investigating possible treatments for AD, but it is unknown if any of them will prove successful. Many measures have been suggested for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease, but there is a lack of adequate support indicating that the degenerative process can be slowed. Mental stimulation, exercise, and a balanced diet are suggested, as both a possible prevention and a sensible way of managing the disease.

Because AD cannot be cured and is degenerative, management of patients is essential. The role of the main caregiver is often taken by the spouse or a close relative. Alzheimer's disease is known for placing a great burden on caregivers; the pressures can be wide-ranging, involving social, psychological, physical, and economic elements of the caregiver's life. In developed countries, AD is one of the most economically costly diseases to society.

Characteristics

The disease course is divided into four stages, with a progressive pattern of cognitive and functional impairment.

Pre-dementia

The first symptoms are often mistaken as related to ageing or stress. Detailed neuropsychological testing can reveal mild cognitive difficulties up to eight years before a person fulfills the clinical criteria for diagnosis of AD. These early symptoms can affect the most complex daily living activities. The most noticeable deficit is memory loss, which shows up as difficulty in remembering recently learned facts and inability to acquire new information. Subtle problems with the executive functions of attentiveness, planning, flexibility, and abstract thinking, or impairments in semantic memory (memory of meanings, and concept relationships), can also be symptomatic of the early stages of AD. Apathy can be observed at this stage, and remains the most persistent neuropsychiatric symptom throughout the course of the disease. The preclinical stage of the disease has also been termed mild cognitive impairment, but there is still debate on whether this term corresponds to a different diagnostic entity by itself or just a first step of the disease.

Early dementia

In people with AD the increasing impairment of learning and memory eventually leads to a definitive diagnosis. In a small proportion of them, difficulties with language, executive functions, perception ( agnosia), or execution of movements ( apraxia) are more prominent than memory problems. AD does not affect all memory capacities equally. Older memories of the person's life ( episodic memory), facts learned ( semantic memory), and implicit memory (the memory of the body on how to do things, such as using a fork to eat) are affected to a lesser degree than new facts or memories. Language problems are mainly characterised by a shrinking vocabulary and decreased word fluency, which lead to a general impoverishment of oral and written language. In this stage, the person with Alzheimer's is usually capable of adequately communicating basic ideas. While performing fine motor tasks such as writing, drawing or dressing, certain movement coordination and planning difficulties ( apraxia) may be present, making sufferers appear clumsy. As the disease progresses, people with AD can often continue to perform many tasks independently, but may need assistance or supervision with the most cognitively demanding activities.

Moderate dementia

Progressive deterioration eventually hinders independence. Speech difficulties become evident due to an inability to recall vocabulary, which leads to frequent incorrect word substitutions ( paraphasias). Reading and writing skills are also progressively lost. Complex motor sequences become less coordinated as time passes, reducing the ability to perform most normal daily living activities. During this phase, memory problems worsen, and the person may fail to recognise close relatives. Long-term memory, which was previously intact, becomes impaired, and behavioural changes become more prevalent. Common neuropsychiatric manifestations are wandering, sundowning, irritability and labile affect, leading to crying, outbursts of unpremeditated aggression, or resistance to caregiving. Approximately 30% of patients also develop illusionary misidentifications and other delusional symptoms. Urinary incontinence can develop. These symptoms create stress for relatives and caretakers, which can be reduced by moving the person from home care to other long-term care facilities.

Advanced dementia

During this last stage of AD, the patient is completely dependent upon caregivers. Language is reduced to simple phrases or even single words, eventually leading to complete loss of speech. Despite the loss of verbal language abilities, patients can often understand and return emotional signals. Although aggressiveness can still be present, extreme apathy and exhaustion are much more common results. Patients will ultimately not be able to perform even the most simple tasks without assistance. Muscle mass and mobility deteriorate to the point where they are bedridden, and they lose the ability to feed themselves. AD is a terminal illness with the cause of death typically being an external factor such as pressure ulcers or pneumonia, not by the disease itself.

Causes

Three major competing hypotheses exist to explain the cause of the disease. The oldest, on which most currently available drug therapies are based, is the cholinergic hypothesis, which proposes that AD is caused by reduced synthesis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The cholinergic hypothesis has not maintained widespread support, largely because medications intended to treat acetylcholine deficiency have not been very effective. Other cholinergic effects have also been proposed, for example, initiation of large-scale aggregation of amyloid, leading to generalised neuroinflammation.

In 1991, the amyloid hypothesis postulated that amyloid beta (Aβ) deposits are the fundamental cause of the disease. Support for this postulate comes from the location of the gene for the amyloid beta precursor protein (APP) on chromosome 21, together with the fact that people with trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome) who thus have an extra gene copy almost universally exhibit AD by 40 years of age. Also APOE4, the major genetic risk factor for AD, leads to excess amyloid buildup in the brain before AD symptoms arise. Thus, Aβ deposition precedes clinical AD. Further evidence comes from the finding that transgenic mice that express a mutant form of the human APP gene develop fibrillar amyloid plaques and Alzheimer's-like brain pathology with spatial learning deficits. An experimental vaccine was found to clear the amyloid plaques in early human trials, but it did not have any significant effect on dementia. Researchers have been led to suspect non-plaque Aβ oligomers (aggregates of many monomers) as the primary pathogenic form of Aβ. In 2009, it was found that oligomeric Aβ exerts a deleterious effect on brain physiology by binding to a specific receptor on neurons. The identity of this receptor is the prion protein that has been linked to mad cow disease and the related human condition, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, thus potentially linking the underlying mechanism of these neurodegenerative disorders with that of Alzheimer's disease..

In 2009, this theory was updated, suggesting that a close relative of the beta-amyloid protein, and not necessarily the beta-amyloid itself, may be a major culprit in the disease. The theory holds that an amyloid-related mechanism that prunes neuronal connections in the brain in the fast-growth phase of early life may be triggered by aging-related processes in later life to cause the neuronal withering of Alzheimer's disease. N-APP, a fragment of APP from the peptide's N-terminus, is adjacent to beta-amyloid and is cleaved from APP by one of the same enzymes. N-APP triggers the self-destruct pathway by binding to a neuronal receptor called death receptor 6 (DR6, also known as TNFRSF21). DR6 is highly expressed in the human brain regions most affected by Alzheimer's, so it is possible that the N-APP/DR6 pathway might be hijacked in the aging brain to cause damage. In this model, Beta-amyloid plays a complementary role, by depressing synaptic function.

A 2004 study found that deposition of amyloid plaques does not correlate well with neuron loss. This observation supports the tau hypothesis, the idea that tau protein abnormalities initiate the disease cascade. In this model, hyperphosphorylated tau begins to pair with other threads of tau. Eventually, they form neurofibrillary tangles inside nerve cell bodies. When this occurs, the microtubules disintegrate, collapsing the neuron's transport system. This may result first in malfunctions in biochemical communication between neurons and later in the death of the cells. Herpes simplex virus type 1 has also been proposed to play a causative role in people carrying the susceptible versions of the apoE gene.

Pathophysiology

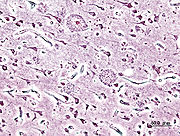

Neuropathology

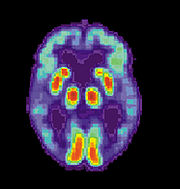

Alzheimer's disease is characterised by loss of neurons and synapses in the cerebral cortex and certain subcortical regions. This loss results in gross atrophy of the affected regions, including degeneration in the temporal lobe and parietal lobe, and parts of the frontal cortex and cingulate gyrus. Studies using MRI and positron emission tomography have documented reductions in the size of specific brain regions in patients as they progressed from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease, and in comparison with similar images from healthy older adults.

Both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are clearly visible by microscopy in brains of those afflicted by AD. Plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of amyloid-beta peptide and cellular material outside and around neurons. Tangles (neurofibrillary tangles) are aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau which has become hyperphosphorylated and accumulate inside the cells themselves. Although many older individuals develop some plaques and tangles as a consequence of ageing, the brains of AD patients have a greater number of them in specific brain regions such as the temporal lobe. Lewy bodies are not rare in AD patient's brains.

Biochemistry

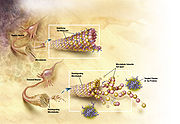

Alzheimer's disease has been identified as a protein misfolding disease ( proteopathy), caused by accumulation of abnormally folded A-beta and tau proteins in the brain. Plaques are made up of small peptides, 39–43 amino acids in length, called beta-amyloid (also written as A-beta or Aβ). Beta-amyloid is a fragment from a larger protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP), a transmembrane protein that penetrates through the neuron's membrane. APP is critical to neuron growth, survival and post-injury repair. In Alzheimer's disease, an unknown process causes APP to be divided into smaller fragments by enzymes through proteolysis. One of these fragments gives rise to fibrils of beta-amyloid, which form clumps that deposit outside neurons in dense formations known as senile plaques.

AD is also considered a tauopathy due to abnormal aggregation of the tau protein. Every neuron has a cytoskeleton, an internal support structure partly made up of structures called microtubules. These microtubules act like tracks, guiding nutrients and molecules from the body of the cell to the ends of the axon and back. A protein called tau stabilises the microtubules when phosphorylated, and is therefore called a microtubule-associated protein. In AD, tau undergoes chemical changes, becoming hyperphosphorylated; it then begins to pair with other threads, creating neurofibrillary tangles and disintegrating the neuron's transport system.

Disease mechanism

Exactly how disturbances of production and aggregation of the beta amyloid peptide gives rise to the pathology of AD is not known. The amyloid hypothesis traditionally points to the accumulation of beta amyloid peptides as the central event triggering neuron degeneration. Accumulation of aggregated amyloid fibrils, which are believed to be the toxic form of the protein responsible for disrupting the cell's calcium ion homeostasis, induces programmed cell death ( apoptosis). It is also known that Aβ selectively builds up in the mitochondria in the cells of Alzheimer's-affected brains, and it also inhibits certain enzyme functions and the utilisation of glucose by neurons.

Various inflammatory processes and cytokines may also have a role in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Inflammation is a general marker of tissue damage in any disease, and may be either secondary to tissue damage in AD or a marker of an immunological response.

Alterations in the distribution of different neurotrophic factors and in the expression of their receptors such as the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been described in AD.

Genetics

The vast majority of cases of Alzheimer's disease are sporadic, meaning that they are not inherited in a manner that is simple to explain. Only about 7% of cases are considered "familial" (FAD); i.e., passed on to 50% of the affected individuals' progeny. Most of these can be attributed to mutations in one of three genes: amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilins 1 and 2. Most mutations in the APP and presenilin genes increase the production of a small protein called Aβ42, which is the main component of senile plaques. But, it appears that this may be oversimplification. Aβ comes in several different sizes, and some of the mutations merely alter the ratio between Aβ42 and the other major forms—e.g., Aβ40—without increasing Aβ42 levels. Mathematically, this suggests that presenilin mutations can cause disease even if they lower the total amount of Aβ produced. This may point to other roles of presenilin or a role for alterations in the function of APP and/or its fragments other than Aβ.

Although most cases of Alzheimer's disease do not exhibit autosomal-dominant inheritance, genetic differences may act as risk factors. The best known genetic risk factor is the inheritance of the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE). This gene is implicated in up to 50% of late-onset sporadic Alzheimer's cases. Geneticists agree that numerous other genes also act as risk factors or have protective effects that influence the development of late onset Alzheimer's disease. Other genes in the biochemical pathway involved in lipoprotein processing appear to be associated with Alzheimer's—for instance SORL1. Over 400 genes have been tested for association with late-onset sporadic AD, most with null results. One candidate from such searches is a variant of the reelin gene that may contribute to Alzheimer's risk in women.

Campion et al. reported that less than 10% of AD cases occurring before 60 years of age are due to autosomal dominant (familial) mutations, thus suggesting that less than 0.01% of all cases are both early-onset and familial. However, Finckh et al. found that their sampling of early-onset dementia yielded 56% with a pathogenic mutation in one of four genes.

Diagnosis

Alzheimer's disease is usually diagnosed clinically from the patient history, collateral history from relatives, and clinical observations, based on the presence of characteristic neurological and neuropsychological features and the absence of alternative conditions. Advanced medical imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to help exclude other cerebral pathology or subtypes of dementia. Assessment of intellectual functioning including memory testing can further characterise the state of the disease. Medical organisations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardise the diagnostic process for practicing physicians. The diagnosis can be confirmed with 100% accuracy post-mortem when brain material is available and can be examined histologically.

Diagnostic criteria

The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA, now known as the Alzheimer's Association) established the most commonly used NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's Criteria for diagnosis in 1984, extensively updated in 2007. These criteria require that the presence of cognitive impairment, and a suspected dementia syndrome, be confirmed by neuropsychological testing for a clinical diagnosis of possible or probable AD. A histopathologic confirmation including a microscopic examination of brain tissue is required for a definitive diagnosis. Good statistical reliability and validity have been shown between the diagnostic criteria and definitive histopathological confirmation. Eight cognitive domains are most commonly impaired in AD—memory, language, perceptual skills, attention, constructive abilities, orientation, problem solving and functional abilities. These domains are equivalent to the NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's Criteria as listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) published by the American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnostic tools

Neuropsychological tests such as the mini-mental state examination (MMSE), are widely used to evaluate the cognitive impairments needed for diagnosis. More comprehensive test arrays are necessary for high reliability of results, particularly in the earliest stages of the disease. Neurological examination in early AD will usually provide normal results, except for obvious cognitive impairment, which may not differ from standard dementia.

Further neurological examinations are crucial in the differential diagnosis of AD and other diseases. Interviews with family members are also utilised in the assessment of the disease. Caregivers can supply important information on the daily living abilities, as well as on the decrease, over time, of the person's mental function. A caregiver's viewpoint is particularly important, since a person with AD is commonly unaware of his own deficits. Many times, families also have difficulties in the detection of initial dementia symptoms and may not communicate accurate information to a physician.

Supplemental testing provides extra information on some features of the disease or is used to rule out other diagnoses. Blood tests can identify other causes for dementia than AD—causes which may, in rare cases, be reversible.

Psychological tests for depression are employed, since depression can either be concurrent with AD (see Depression of Alzheimer disease), an early sign of cognitive impairment, or even the cause.

When available as a diagnostic tool, SPECT and PET neuroimaging are used to confirm a diagnosis of Alzheimer's in conjunction with evaluations involving mental status examination.In a person already having dementia, SPECT appears to be superior in differentiating Alzheimer's disease from other possible causes, compared with the usual attempts employing mental testing and medical history analysis. Another recent objective marker of the disease is the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid for amyloid beta or tau proteins. Both advances have led to the proposal of new diagnostic criteria. A new technique known as PiB PET has been developed for directly and clearly imaging beta-amyloid deposits in vivo using a tracer that binds selectively to the Abeta deposits. Recent studies suggest that PIB-PET is 86% accurate in predicting which people with mild cognitive impairment will develop Alzheimer's disease within two years, and 92% accurate in ruling out the likelihood of developing Alzheimer's. Volumetric MRI, which can detect changes in the size of brain regions that atrophy during the progress of Alzheimer's disease, is also showing promise as a diagnostic method. It may prove less expensive than other imaging methods currently under study.

Prevention

At present, there is no definitive evidence to support that any particular measure is effective in preventing AD. Global studies of measures to prevent or delay the onset of AD have often produced inconsistent results. However, epidemiological studies have proposed relationships between certain modifiable factors, such as diet, cardiovascular risk, pharmaceutical products, or intellectual activities among others, and a population's likelihood of developing AD. Only further research, including clinical trials, will reveal whether these factors can help to prevent AD.

Although cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, are associated with a higher risk of onset and course of AD, statins, which are cholesterol lowering drugs, have not been effective in preventing or improving the course of the disease. The components of a Mediterranean diet, which include fruit and vegetables, bread, wheat and other cereals, olive oil, fish, and red wine, may all individually or together reduce the risk and course of Alzheimer's disease. Its beneficial cardiovascular effect has been proposed as the mechanism of action. There is limited evidence that light to moderate use of alcohol, particularly red wine, is associated with lower risk of AD.

Reviews on the use of vitamins have not found enough evidence of efficacy to recommend vitamin C, E, or folic acid with or without vitamin B12, as preventive or treatment agents in AD. Additionally vitamin E is associated with important health risks.

Long-term usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) is associated with a reduced likelihood of developing AD. Human postmortem studies, in animal models, or in vitro investigations also support the notion that NSAIDs can reduce inflammation related to amyloid plaques. However trials investigating their use as palliative treatment have failed to show positive results while no prevention trial has been completed. Curcumin from the curry spice turmeric has shown some effectiveness in preventing brain damage in mouse models due to its anti-inflammatory properties. Hormone replacement therapy, although previously used, is no longer thought to prevent dementia and in some cases may even be related to it. There is inconsistent and unconvincing evidence that ginkgo has any positive effect on cognitive impairment and dementia, and a recent study concludes that it has no effect in reducing the rate of AD incidence. A 21-year study found that coffee drinkers of 3-5 cups day at midlife had a 65% reduction in risk of dementia in late-life.

People who engage in intellectual activities such as reading, playing board games, completing crossword puzzles, playing musical instruments, or regular social interaction show a reduced risk for Alzheimer's disease. This is compatible with the cognitive reserve theory; which states that some life experiences result in more efficient neural functioning providing the individual a cognitive reserve that delays the onset of dementia manifestations. Education delays the onset of AD syndrome, but is not related to earlier death after diagnosis. Physical activity is also associated with a reduced risk of AD.

Some studies have shown an increased risk of developing AD with environmental factors such the intake of metals, particularly aluminium, or exposure to solvents. The quality of some of these studies has been criticised, and other studies have concluded that there is no relationship between these environmental factors and the development of AD. Electromagnetic fields (EMF) have also been proposed to be related to AD by some experts, but not others. Regarding extremely low frequency EMFs, while a metanalysis found that exposed people had more than two-fold probabilities of having the disease, reviews do not agree on whether studies point towards a relationship, or not. Doubts on how to interpret the statistically significant results of the metaanalysis have been raised.

Management

There is no cure for Alzheimer's disease; available treatments offer relatively small symptomatic benefit but remain palliative in nature. Current treatments can be divided into pharmaceutical, psychosocial and caregiving.

Pharmaceutical

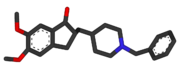

Four medications are currently approved by regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) to treat the cognitive manifestations of AD: three are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the other is memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist. No drug has an indication for delaying or halting the progression of the disease.

Reduction in the activity of the cholinergic neurons is a well-known feature of Alzheimer's disease. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are employed to reduce the rate at which acetylcholine (ACh) is broken down, thereby increasing the concentration of ACh in the brain and combating the loss of ACh caused by the death of cholinergic neurons. As of 2008, the cholinesterase inhibitors approved for the management of AD symptoms are donepezil (brand name Aricept), galantamine (Razadyne), and rivastigmine (branded as Exelon and Exelon Patch). There is evidence for the efficacy of these medications in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, and some evidence for their use in the advanced stage. Only donepezil is approved for treatment of advanced AD dementia. The use of these drugs in mild cognitive impairment has not shown any effect in a delay of the onset of AD. The most common side effects are nausea and vomiting, both of which are linked to cholinergic excess. These side effects arise in approximately 10-20% of users and are mild to moderate in severity. Less common secondary effects include muscle cramps, decreased heart rate ( bradycardia), decreased appetite and weight, and increased gastric acid production.

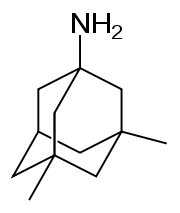

Glutamate is a useful excitatory neurotransmitter of the nervous system, although excessive amounts in the brain can lead to cell death through a process called excitotoxicity which consists of the overstimulation of glutamate receptors. Excitotoxicity occurs not only in Alzheimer's disease, but also in other neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis. Memantine (brand names Akatinol, Axura, Ebixa/Abixa, Memox and Namenda), is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist first used as an anti-influenza agent. It acts on the glutamatergic system by blocking NMDA receptors and inhibiting their overstimulation by glutamate. Memantine has been shown to be moderately efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Its effects in the initial stages of AD are unknown. Reported adverse events with memantine are infrequent and mild, including hallucinations, confusion, dizziness, headache and fatigue. The combination of memantine and donepezil has been shown to be "of statistically significant but clinically marginal effectiveness".

Antipsychotic drugs are modestly useful in reducing aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's patients with behavioural problems, but are associated with serious adverse effects, such as cerebrovascular events, movement difficulties or cognitive decline, that do not permit their routine use. When used in the long-term, they have been shown to associate with increased mortality.

Psychosocial intervention

Psychosocial interventions are used as an adjunct to pharmaceutical treatment and can be classified within behaviour-, emotion-, cognition- or stimulation-oriented approaches. Research on efficacy is unavailable and rarely specific to AD, focusing instead on dementia in general.

Behavioural interventions attempt to identify and reduce the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviours. This approach has not shown success in improving overall functioning, but can help to reduce some specific problem behaviours, such as incontinence. There is a lack of high quality data on the effectiveness of these techniques in other behaviour problems such as wandering.

Emotion-oriented interventions include reminiscence therapy, validation therapy, supportive psychotherapy, sensory integration, also called snoezelen, and simulated presence therapy. Supportive psychotherapy has received little or no formal scientific study, but some clinicians find it useful in helping mildly impaired patients adjust to their illness. Reminiscence therapy (RT) involves the discussion of past experiences individually or in group, many times with the aid of photographs, household items, music and sound recordings, or other familiar items from the past. Although there are few quality studies on the effectiveness of RT, it may be beneficial for cognition and mood. Simulated presence therapy (SPT) is based on attachment theories and involves playing a recording with voices of the closest relatives of the person with Alzheimer's disease. There is partial evidence indicating that SPT may reduce challenging behaviours. Finally, validation therapy is based on acceptance of the reality and personal truth of another's experience, while sensory integration is based on exercises aimed to stimulate senses. There is little evidence to support the usefulness of these therapies.

The aim of cognition-oriented treatments, which include reality orientation and cognitive retraining, is the reduction of cognitive deficits. Reality orientation consists in the presentation of information about time, place or person in order to ease the understanding of the person about its surroundings and his or her place in them. On the other hand cognitive retraining tries to improve impaired capacities by exercitation of mental abilities. Both have shown some efficacy improving cognitive capacities, although in some studies these effects were transient and negative effects, such as frustration, have also been reported.

Stimulation-oriented treatments include art, music and pet therapies, exercise, and any other kind of recreational activities. Stimulation has modest support for improving behaviour, mood, and, to a lesser extent, function. Nevertheless, as important as these effects are, the main support for the use of stimulation therapies is the change in the person's routine.

Caregiving

Since Alzheimer's has no cure and it gradually renders people incapable of tending for their own needs, caregiving essentially is the treatment and must be carefully managed over the course of the disease.

During the early and moderate stages, modifications to the living environment and lifestyle can increase patient safety and reduce caretaker burden. Examples of such modifications are the adherence to simplified routines, the placing of safety locks, the labelling of household items to cue the person with the disease or the use of modified daily life objects. The patient may also become incapable of feeding themselves, so they require food in smaller pieces or pureed. When swallowing difficulties arise, the use of feeding tubes may be required. In such cases, the medical efficacy and ethics of continuing feeding is an important consideration of the caregivers and family members. The use of physical restraints is rarely indicated in any stage of the disease, although there are situations when they are necessary to prevent harm to the person with AD or their caregivers.

As the disease progresses, different medical issues can appear, such as oral and dental disease, pressure ulcers, malnutrition, hygiene problems, or respiratory, skin, or eye infections. Careful management can prevent them, while professional treatment is needed when they do arise. During the final stages of the disease, treatment is centred on relieving discomfort until death.

Prognosis

The early stages of Alzheimer's disease are difficult to diagnose. A definitive diagnosis is usually made once cognitive impairment compromises daily living activities, although the person may still be living independently. He will progress from mild cognitive problems, such as memory loss through increasing stages of cognitive and non-cognitive disturbances, eliminating any possibility of independent living.

Life expectancy of the population with the disease is reduced. The mean life expectancy following diagnosis is approximately seven years. Fewer than 3% of patients live more than fourteen years. Disease features significantly associated with reduced survival are an increased severity of cognitive impairment, decreased functional level, history of falls, and disturbances in the neurological examination. Other coincident diseases such as heart problems, diabetes or history of alcohol abuse are also related with shortened survival. While the earlier the age at onset the higher the total survival years, life expectancy is particularly reduced when compared to the healthy population among those who are younger. Men have a less favourable survival prognosis than women.

The disease is the underlying cause of death in 70% of all cases. Pneumonia and dehydration are the most frequent immediate causes of death, while cancer is a less frequent cause of death than in the general population.

Epidemiology

| Age | New affected per thousand person–years |

|---|---|

| 65–69 | 3 |

| 70–74 | 6 |

| 75–79 | 9 |

| 80–84 | 23 |

| 85–89 | 40 |

| 90– | 69 |

Two main measures are used in epidemiological studies: incidence and prevalence. Incidence is the number of new cases per unit of person–time at risk (usually number of new cases per thousand person–years); while prevalence is the total number of cases of the disease in the population at a given time.

Regarding incidence, cohort longitudinal studies (studies where a disease-free population is followed over the years) provide rates between 10–15 per thousand person–years for all dementias and 5–8 for AD, which means that half of new dementia cases each year are AD. Advancing age is a primary risk factor for the disease and incidence rates are not equal for all ages: every five years after the age of 65, the risk of acquiring the disease approximately doubles, increasing from 3 to as much as 69 per thousand person years. There are also sex differences in the incidence rates, women having a higher risk of developing AD particularly in the population older than 85.

Prevalence of AD in populations is dependent upon different factors including incidence and survival. Since the incidence of AD increases with age, it is particularly important to include the mean age of the population of interest. In the United States, Alzheimer prevalence was estimated to be 1.6% in the year 2000 both overall and in the 65–74 age group, with the rate increasing to 19% in the 75–84 group and to 42% in the greater than 84 group. Prevalence rates in less developed regions are lower. The World Health Organization estimated that in 2005, 0.379% of people worldwide had dementia, and that the prevalence would increase to 0.441% in 2015 and to 0.556% in 2030. Other studies have reached similar conclusions. Another study estimated that in 2006, 0.40% of the world population (range 0.17–0.89%; absolute number 26.6 million, range 11.4–59.4 million) were afflicted by AD, and that the prevalence rate would triple and the absolute number would quadruple by the year 2050.

History

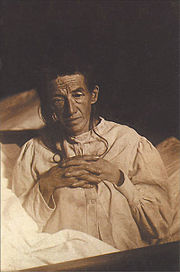

The ancient Greek and Roman philosophers and physicians associated old age with increasing dementia. It was not until 1901 that German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer identified the first case of what became known as Alzheimer's disease in a fifty-year-old woman he called Auguste D. Alzheimer followed her until she died in 1906, when he first reported the case publicly. During the next five years, eleven similar cases were reported in the medical literature, some of them already using the term Alzheimer's disease. The disease was first described as a distinctive disease by Emil Kraepelin after suppressing some of the clinical (delusions and hallucinations) and pathological features (arteriosclerotic changes) contained in the original report of Auguste D. He included Alzheimer’s disease, also named presenile dementia by Kraepelin, as a subtype of senile dementia in the eighth edition of his Textbook of Psychiatry, published in 1910 .

For most of the twentieth century, the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease was reserved for individuals between the ages of 45 and 65 who developed symptoms of dementia. The terminology changed after 1977 when a conference on AD concluded that the clinical and pathological manifestations of presenile and senile dementia were almost identical, although the authors also added that this did not rule out the possibility of different aetiologies. This eventually led to the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease independently of age. The term senile dementia of the Alzheimer type (SDAT) was used for a time to describe the condition in those over 65, with classical Alzheimer's disease being used for those younger. Eventually, the term Alzheimer's disease was formally adopted in medical nomenclature to describe individuals of all ages with a characteristic common symptom pattern, disease course, and neuropathology.

Society and culture

Social costs

Dementia, and specifically Alzheimer's disease, may be among the most costly diseases for society in Europe and the United States, while their cost in other countries such as Argentina, or South Korea, is also high and rising. These costs will probably increase with the ageing of society, becoming an important social problem. AD-associated costs include direct medical costs such as nursing home care, direct nonmedical costs such as in-home day care, and indirect costs such as lost productivity of both patient and caregiver. Numbers vary between studies but dementia costs worldwide have been calculated around $160 billion, while costs of Alzheimer in the United States may be $100 billion each year.

The greatest origin of costs for society is the long-term care by health care professionals and particularly institutionalisation, which corresponds to 2/3 of the total costs for society. The cost of living at home is also very high, especially when informal costs for the family, such as caregiving time and caregiver's lost earnings, are taken into account.

Costs increase with dementia severity and the presence of behavioural disturbances, and are related to the increased caregiving time required for the provision of physical care. Therefore any treatment that slows cognitive decline, delays institutionalisation or reduces caregivers' hours will have economic benefits. Economic evaluations of current treatments have shown positive results.

Caregiving burden

The role of the main caregiver is often taken by the spouse or a close relative. Alzheimer's disease is known for placing a great burden on caregivers which includes social, psychological, physical or economic aspects. Home care is usually preferred by patients and families. This option also delays or eliminates the need for more professional and costly levels of care. Nevertheless two-thirds of nursing home residents have dementias.

Dementia caregivers are subject to high rates of physical and mental disorders. Factors associated with greater psychosocial problems of the primary caregivers include having an affected person at home, the carer being a spouse, demanding behaviours of the cared person such as depression, behavioural disturbances, hallucinations, sleep problems or walking disruptions and social isolation. Regarding economic problems, family caregivers often give up time from work to spend 47 hours per week on average with the person with AD, while the costs of caring for them are high. Direct and indirect costs of caring for an Alzheimer's patient average between $18,000 and $77,500 per year in the United States, depending on the study.

Cognitive behavioural therapy and the teaching of coping strategies either individually or in group have demonstrated their efficacy in improving caregivers' psychological health.

Notable cases

As Alzheimer's disease is highly prevalent, many notable people have developed it. Well-known examples are former United States President Ronald Reagan and Irish writer Iris Murdoch, both of whom were the subjects of scientific articles examining how their cognitive capacities deteriorated with the disease. Other notable cases include the retired footballer Ferenc Puskas, the former Prime Ministers Harold Wilson (United Kingdom) and Adolfo Suárez (Spain), the actress Rita Hayworth, the actor Charlton Heston, and the novelist Terry Pratchett.

AD has also been portrayed in films such as: Iris (2001), based on John Bayley's memoir of his wife Iris Murdoch; The Notebook (2004), based on Nicholas Sparks' 1996 novel of the same name; Thanmathra (2005); Memories of Tomorrow (Ashita no Kioku) (2006), based on Hiroshi Ogiwara's novel of the same name; and Away from Her (2006), based on Alice Munro's short story " The Bear Came over the Mountain". Documentaries on Alzheimer's disease include Malcolm and Barbara: A Love Story (1999) and Malcolm and Barbara: Love’s Farewell (2007), both featuring Malcolm Pointon.

Research directions

As of 2008, the safety and efficacy of more than 400 pharmaceutical treatments are being investigated in clinical trials worldwide, and approximately one-fourth of these compounds are in Phase III trials, which is the last step prior to review by regulatory agencies.

One area of clinical research is focused on treating the underlying disease pathology. Reduction of amyloid beta levels is a common target of compounds under investigation. Immunotherapy or vaccination for the amyloid protein is one treatment modality under study. Unlike preventative vaccination, the putative therapy would be used to treat people already diagnosed. It is based upon the concept of training the immune system to recognise, attack, and reverse deposition of amyloid, thereby altering the course of the disease. An example of such a vaccine under investigation was ACC-001, although the trials were suspended in 2008. Another similar agent is bapineuzumab, an antibody designed as identical to the naturally induced anti-amyloid antibody. Other approaches are neuroprotective agents, such as AL-108, and metal-protein interaction attenuation agents, such as PBT2. A TNFα receptor fusion protein, etanercept has showed encouraging results.

In 2008, two separate clinical trials showed positive results in modifying the course of disease in mild to moderate AD with methylthioninium chloride (trade name rember), a drug that inhibits tau aggregation, and dimebon, an antihistamine.