Aspirin

About this schools Wikipedia selection

This Wikipedia selection is available offline from SOS Children for distribution in the developing world. Click here for more information on SOS Children.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 2-acetoxybenzoic acid | |

| Clinical data | |

| AHFS/ Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682878 |

| Pregnancy cat. | C (AU) D (US) |

| Legal status | Unscheduled (AU) GSL (UK) OTC (US) |

| Routes | Most commonly oral, also rectal, lysine acetylsalicylate may be given IV or IM |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Rapidly and completely absorbed |

| Protein binding | 99.6% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Half-life | 300–650 mg dose: 3.1–3.2 h 1 g dose: 5 h 2 g dose: 9 h |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 50-78-2 |

| ATC code | A01 AD05 B01 AC06, N02 BA01 |

| PubChem | CID 2244 |

| DrugBank | DB00945 |

| ChemSpider | 2157 |

| UNII | R16CO5Y76E |

| KEGG | D00109 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15365 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL25 |

| Synonyms | 2-acetyloxybenzoic acid acetylsalicylate acetylsalicylic acid O-acetylsalicylic acid |

| Chemical data | |

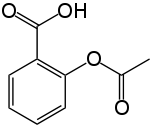

| Formula | C9H8O4 |

| Mol. mass | 180.157 g/mol |

|

SMILES

|

|

|

InChI

|

|

| Physical data | |

| Density | 1.40 g/cm³ |

| Melt. point | 136 °C (277 °F) |

| Boiling point | 140 °C (284 °F) (decomposes) |

| Solubility in water | 3 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

|

Aspirin ( USAN), also known as acetylsalicylic acid ( / ə ˌ s ɛ t əl ˌ s æ l ɨ ˈ s ɪ l ɨ k / ə-SET-əl-SAL-i-SIL-ik; abbreviated ASA), is a salicylate drug, often used as an analgesic to relieve minor aches and pains, as an antipyretic to reduce fever, and as an anti-inflammatory medication. Aspirin was first isolated by Felix Hoffmann, a chemist with the German company Bayer in 1897.

Salicylic acid, the main metabolite of aspirin, is an integral part of human and animal metabolism. While in humans much of it is attributable to diet, a substantial part is synthesized endogenously.

Aspirin also has an antiplatelet effect by inhibiting the production of thromboxane, which under normal circumstances binds platelet molecules together to create a patch over damaged walls of blood vessels. Because the platelet patch can become too large and also block blood flow, locally and downstream, aspirin is also used long-term, at low doses, to help prevent heart attacks, strokes, and blood clot formation in people at high risk of developing blood clots. It has also been established that low doses of aspirin may be given immediately after a heart attack to reduce the risk of another heart attack or of the death of cardiac tissue. Aspirin may be effective at preventing certain types of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer.

The main undesirable side effects of aspirin taken by mouth are gastrointestinal ulcers, stomach bleeding, and tinnitus, especially in higher doses. In children and adolescents, aspirin is no longer indicated to control flu-like symptoms or the symptoms of chickenpox or other viral illnesses, because of the risk of Reye's syndrome.

Aspirin is part of a group of medications called nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but differs from most other NSAIDs in the mechanism of action. Though it, and others in its group called the salicylates, have similar effects (antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic) to the other NSAIDs and inhibit the same enzyme cyclooxygenase, aspirin (but not the other salicylates) does so in an irreversible manner and, unlike others, affects more the COX-1 variant than the COX-2 variant of the enzyme.

Today, aspirin is one of the most widely used medications in the world, with an estimated 40,000 tonnes of it being consumed each year. In countries where Aspirin is a registered trademark owned by Bayer, the generic term is acetylsalicylic acid (ASA).

Medical use

Aspirin is used in the treatment of a number of conditions, including fever, pain, rheumatic fever, and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, pericarditis, and Kawasaki disease. Lower doses of aspirin have also shown to reduce the risk of death from a heart attack, or the risk of stroke in some circumstances. There is some evidence that aspirin is effective at preventing colorectal cancer, though the mechanisms of this effect are unclear.

Pain

In most cases, aspirin is considered inferior to ibuprofen for the alleviation of pain, because aspirin is more likely to cause gastrointestinal bleeding. Aspirin is generally ineffective for those pains caused by muscle cramps, bloating, gastric distension, or acute skin irritation. As with other NSAIDs, combinations of aspirin and caffeine provide slightly greater pain relief than aspirin alone. Effervescent formulations of aspirin, such as Alka-Seltzer or Blowfish, relieve pain faster than aspirin in tablets, which makes them useful for the treatment of migraines.

Topical aspirin may be effective for treating some types of neuropathic pain.

Headache

Aspirin, either by itself or in combined formulation, effectively treats some types of headache, but its efficacy may be questionable for others. Secondary headaches, meaning those caused by another disorder or trauma, should be promptly treated by a medical provider.

Among primary headaches, the International Classification of Headache Disorders distinguishes between tension headache (the most common), migraine, and cluster headache. Aspirin or other over-the-counter analgesics are widely recognized as effective for the treatment of tension headache. Aspirin, especially as a component of an acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine formulation (e.g. Excedrin Migraine), is considered a first-line therapy in the treatment of migraine, and comparable to lower doses of sumatriptan. It is most effective at stopping migraines when they are first beginning. Few data suggest the effectiveness of aspirin for the treatment of cluster headache.

Fever

Like its ability to control pain, aspirin's ability to control fever is due to its action on the prostaglandin system through its irreversible inhibition of COX. Although aspirin's use as an antipyretic in adults is well-established, many medical societies and regulatory agencies (including the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the United States Food and Drug Administration) strongly advise against using aspirin for treatment of fever in children because of the risk of Reye's syndrome, a rare but often fatal illness associated with the use of aspirin or other salicylates in children during episodes of viral or bacterial infection. Because of the risk of Reye's syndrome in children, in 1986 the FDA required labeling on all aspirin-containing medications advising against its use in children and teenagers.

Heart attacks and strokes

For a subset of the population, aspirin may help prevent heart attacks and strokes. In lower doses, aspirin has been known to prevent the progression of existing cardiovascular disease, and reduce the frequency of these events for those with a history of them. (This is known as secondary prevention.)

Aspirin appears to offer little benefit to those at lower risk of heart attack or stroke—for instance, those without a history of these events or with pre-existing disease. (This is called primary prevention.) Some studies recommend aspirin on a case-by-case basis, while others have suggested that the risks of other events, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, were significant enough to outweigh any potential benefit, and recommended against using aspirin for primary prevention entirely.

Complicating the use of aspirin for prevention is the phenomenon of aspirin resistance. For patients who are resistant, aspirin's efficacy is reduced, which can cause an increased risk of stroke. Some authors have suggested testing regimes to identify those patients who are resistant to aspirin or other anti-thrombotic drugs (such as clopidogrel).

Aspirin has also been suggested as a component of a polypill for prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Post-surgery

After percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs), such as the placement of a coronary artery stent, a US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality guideline recommends that aspirin be taken indefinitely. Frequently, aspirin is combined with an ADP receptor inhibitor, such as clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor to prevent blood clots. This is called dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT). US and EU guidelines disagree somewhat about how long, and for what indications this combined therapy should be continued post-surgery. US guidelines recommend DAPT for at least 12 months while EU guidelines recommend DAPT for 6–12 months after drug eluting stent. However, they agree that aspirin be continued indefinitely after DAPT is complete.

Cancer prevention

Aspirin's effect on cancer has been widely studied, particularly its effect on colorectal cancer (CRC). Multiple meta-analyses and reviews have concluded that regular use of aspirin reduces the long-term risk of CRC incidence and mortality. However, the relationships of aspirin dose and duration of use to the various types of CRC risk, including mortality, progression, and incidence, are not well-defined. While the majority of data on aspirin and CRC risk comes from observational studies, rather than randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the available data from RCTs suggests that long-term use of low dose aspirin may be effective at preventing some types of CRC. In the 2007 USPSTF guidelines on this topic, use of aspirin for prevention of CRC was given a "D" rating, advising healthcare practitioners against routinely using aspirin for this purpose.

Other uses

Aspirin is a first-line treatment for the fever and joint pain symptoms of acute rheumatic fever. The therapy often lasts for one to two weeks, and is rarely indicated for longer periods. After fever and pain have subsided, the aspirin is no longer necessary, since it does not decrease the incidence of heart complications and residual rheumatic heart disease. Naproxen has been shown to be as effective as aspirin and less toxic, but due to the limited clinical experience, naproxen is recommended only as a second-line treatment.

Along with rheumatic fever, Kawasaki disease remains one of the few indications for aspirin use in children in spite of a lack of high quality evidence for its effectiveness.

Low dose aspirin supplementation has moderate benefits when used for prevention of pre-eclampsia.

Resistance

For some people, aspirin does not have as strong an effect on platelets as for others, an effect known as aspirin resistance or insensitivity. One study has suggested women are more likely to be resistant than men, and a different, aggregate study of 2,930 patients found 28% were resistant. A study in 100 Italian patients, on the other hand, found that, of the apparent 31% aspirin-resistant subjects, only 5% were truly resistant, and the others were noncompliant. Another study of 400 healthy volunteers found no subjects who were truly resistant, but some had "pseudoresistance, reflecting delayed and reduced drug absorption."

Dosage

Adult aspirin tablets are produced in standardised sizes, which vary slightly from country to country, for example 300 mg in Britain and 325 mg in the USA. Smaller doses are based on these standards; e.g. 75- and 81-mg tablets are used (81-mg tablets can be referred to as "baby-strength" aspirin); there is no medical significance in the slight difference. Of historical interest, in the US, a 325-mg dose is equivalent to the historic 5- grain aspirin tablet in use prior to the metric system.

In general, for adults, doses are taken four times a day for fever or arthritis, with doses near the maximal daily dose used historically for the treatment of rheumatic fever. For the prevention of myocardial infarction in someone with documented or suspected coronary artery disease, much lower doses are taken once daily.

New recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force on the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease encourage men aged 45–79 and women aged 55–79 to use aspirin when the potential benefit of a reduction in myocardial infarction (MI) for men or stroke for women outweighs the potential harm of an increase in gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The WHI study said regular low dose (75 or 81 mg) aspirin female users had a 25% lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease and a 14% lower risk of death from any cause. Low dose aspirin use was also associated with a trend toward lower risk of cardiovascular events, and lower aspirin doses (75 or 81 mg/day) may optimize efficacy and safety for patients requiring aspirin for long-term prevention.

In children with Kawasaki disease, aspirin is taken at dosages based on body weight, initially four times a day for up to two weeks and then at a lower dose once daily for a further six to eight weeks.

Adverse effects

Contraindications

Aspirin should not be taken by people who are allergic to ibuprofen or naproxen, or who have salicylate intolerance or a more generalized drug intolerance to NSAIDs, and caution should be exercised in those with asthma or NSAID-precipitated bronchospasm. Owing to its effect on the stomach lining, manufacturers recommend people with peptic ulcers, mild diabetes, or gastritis seek medical advice before using aspirin. Even if none of these conditions is present, the risk of stomach bleeding is still increased when aspirin is taken with alcohol or warfarin. Patients with hemophilia or other bleeding tendencies should not take aspirin or other salicylates. Aspirin is known to cause hemolytic anaemia in people who have the genetic disease glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, particularly in large doses and depending on the severity of the disease. Use of aspirin during dengue fever is not recommended owing to increased bleeding tendency. People with kidney disease, hyperuricemia, or gout should not take aspirin because it inhibits the kidneys' ability to excrete uric acid, and thus may exacerbate these conditions. Aspirin should not be given to children or adolescents to control cold or influenza symptoms, as this has been linked with Reye's syndrome.

Gastrointestinal

Aspirin use has been shown to increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Although some enteric-coated formulations of aspirin are advertised as being "gentle to the stomach", in one study, enteric coating did not seem to reduce this risk. Combining aspirin with other NSAIDs has also been shown to further increase this risk. Using aspirin in combination with clopidogrel or warfarin also increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

In addition to enteric coating, "buffering" is the other main method companies have used to try to mitigate the problem of gastrointestinal bleeding. Buffering agents are intended to work by preventing the aspirin from concentrating in the walls of the stomach, although the benefits of buffered aspirin are disputed. Almost any buffering agent used in antacids can be used; Bufferin, for example, uses MgO. Other preparations use CaCO3.

Taking it with vitamin C is a more recently investigated method of protecting the stomach lining. Taking equal doses of vitamin C and aspirin decreases the amount of stomach damage that occurs compared to taking aspirin alone.

Central effects

Large doses of salicylate, a metabolite of aspirin, have been proposed to cause tinnitus (ringing in the ears) based on experiments in rats, via the action on arachidonic acid and NMDA receptors cascade.

Reye's syndrome

Reye's syndrome, a rare but severe illness characterized by acute encephalopathy and fatty liver, can occur when children or adolescents are given aspirin for a fever or other illnesses or infections. From 1981 through 1997, 1207 cases of Reye's syndrome in under-18 patients were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of these, 93% reported being ill in the three weeks preceding onset of Reye's syndrome, most commonly with a respiratory infection, chickenpox, or diarrhea. Salicylates were detectable in 81.9% of children for whom test results were reported. After the association between Reye's syndrome and aspirin was reported, and safety measures to prevent it (including a Surgeon General's warning, and changes to the labeling of aspirin-containing drugs) were implemented, aspirin taken by children declined considerably in the United States, as did the number of reported cases of Reye's syndrome; a similar decline was found in the United Kingdom after warnings against pediatric aspirin use were issued. The US Food and Drug Administration now recommends aspirin (or aspirin-containing products) should not be given to anyone under the age of 12 who has a fever, and the British Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency recommends children who are under 16 years of age should not take aspirin, unless it is on the advice of a doctor.

Hives and swelling

For a small number of people, taking aspirin can result in symptoms resembling an allergic reaction, including hives, swelling and headache. The reaction is caused by salicylate intolerance and is not a true allergy, but rather an inability to metabolize even small amounts of aspirin, resulting in an overdose.

Other adverse effects

Aspirin can induce angioedema (swelling of skin tissues) in some people. In one study, angioedema appeared one to six hours after ingesting aspirin in some of the patients. However, when the aspirin was taken alone, it did not cause angioedema in these patients; the aspirin had been taken in combination with another NSAID-induced drug when angioedema appeared.

Aspirin causes an increased risk of cerebral microbleeds having the appearance on MRI scans of 5- to 10-mm or smaller, hypointense (dark holes) patches. Such cerebral microbleeds are important, since they often occur prior to ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage, Binswanger disease and Alzheimer's disease.

A study of a group with a mean dosage of aspirin of 270 mg per day estimated an average absolute risk increase in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) of 12 events per 10,000 persons. In comparison, the estimated absolute risk reduction in myocardial infarction was 137 events per 10,000 persons, and a reduction of 39 events per 10,000 persons in ischemic stroke. In cases where ICH already has occurred, aspirin use results in higher mortality, with a dose of approximately 250 mg per day resulting in a relative risk of death within three months after the ICH of approximately 2.5 (95% confidence interval 1.3 to 4.6).

Aspirin and other NSAIDs can cause hyperkalemia by inducing a hyporenin hypoaldosteronic state via inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis; however, these agents do not typically cause hyperkalemia by themselves in the setting of normal renal function and euvolemic state.

Aspirin can cause prolonged bleeding after operations for up to 10 days. In one study, 30 of 6499 elective surgical patients required reoperations to control bleeding. Twenty had diffuse bleeding and 10 had bleeding from a site. Diffuse, but not discrete, bleeding was associated with the preoperative use of aspirin alone or in combination with other NSAIDS in 19 of the 20 diffuse bleeding patients.

| Condition | Prothrombin time | Partial thromboplastin time | Bleeding time | Platelet count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K deficiency or warfarin | Prolonged | Normal or mildly prolonged | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Prolonged | Prolonged | Prolonged | Decreased |

| Von Willebrand disease | Unaffected | Prolonged | Prolonged | Unaffected |

| Hemophilia | Unaffected | Prolonged | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Aspirin | Unaffected | Unaffected | Prolonged | Unaffected |

| Thrombocytopenia | Unaffected | Unaffected | Prolonged | Decreased |

| Liver failure, early | Prolonged | Unaffected | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Liver failure, end-stage | Prolonged | Prolonged | Prolonged | Decreased |

| Uremia | Unaffected | Unaffected | Prolonged | Unaffected |

| Congenital afibrinogenemia | Prolonged | Prolonged | Prolonged | Unaffected |

| Factor V deficiency | Prolonged | Prolonged | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Factor X deficiency as seen in amyloid purpura | Prolonged | Prolonged | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Glanzmann's thrombasthenia | Unaffected | Unaffected | Prolonged | Unaffected |

| Bernard-Soulier syndrome | Unaffected | Unaffected | Prolonged | Decreased or unaffected |

| Factor XII deficiency | Unaffected | Prolonged | Unaffected | Unaffected |

Overdose

Aspirin overdose can be acute or chronic. In acute poisoning, a single large dose is taken; in chronic poisoning, higher than normal doses are taken over a period of time. Acute overdose has a mortality rate of 2%. Chronic overdose is more commonly lethal, with a mortality rate of 25%; chronic overdose may be especially severe in children. Toxicity is managed with a number of potential treatments, including activated charcoal, intravenous dextrose and normal saline, sodium bicarbonate, and dialysis. The diagnosis of poisoning usually involves measurement of plasma salicylate, the active metabolite of aspirin, by automated spectrophotometric methods. Plasma salicylate levels in general range from 30–100 mg/l after usual therapeutic doses, 50–300 mg/l in patients taking high doses and 700–1400 mg/l following acute overdose. Salicylate is also produced as a result of exposure to bismuth subsalicylate, methyl salicylate and sodium salicylate.

Interactions

Aspirin is known to interact with other drugs. For example, acetazolamide and ammonium chloride are known to enhance the intoxicating effect of salicyclates, and alcohol also increases the gastrointestinal bleeding associated with these types of drugs. Aspirin is known to displace a number of drugs from protein-binding sites in the blood, including the antidiabetic drugs tolbutamide and chlorpropamide, the immunosuppressant methotrexate, phenytoin, probenecid, valproic acid (as well as interfering with beta oxidation, an important part of valproate metabolism) and any NSAID. Corticosteroids may also reduce the concentration of aspirin. Ibuprofen can negate the antiplatelet effect of aspirin used for cardioprotection and stroke prevention. The pharmacological activity of spironolactone may be reduced by taking aspirin, and aspirin is known to compete with penicillin G for renal tubular secretion. Aspirin may also inhibit the absorption of vitamin C.

Chemical properties

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) decomposes rapidly in solutions of ammonium acetate or of the acetates, carbonates, citrates or hydroxides of the alkali metals. ASA is stable in dry air, but gradually hydrolyses in contact with moisture to acetic and salicylic acids. In solution with alkalis, the hydrolysis proceeds rapidly and the clear solutions formed may consist entirely of acetate and salicylate.

Physical properties

Aspirin, an acetyl derivative of salicylic acid, is a white, crystalline, weakly acidic substance, with a melting point of 136 °C (277 °F), and a boiling point of 140 °C (284 °F).

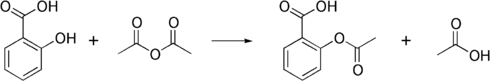

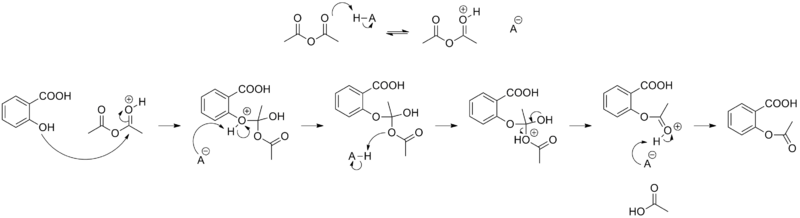

Synthesis

The synthesis of aspirin is classified as an esterification reaction. Salicylic acid is treated with acetic anhydride, an acid derivative, causing a chemical reaction that turns salicylic acid's hydroxyl group into an ester group (R-OH → R-OCOCH3). This process yields aspirin and acetic acid, which is considered a byproduct of this reaction. Small amounts of sulfuric acid (and occasionally phosphoric acid) are almost always used as a catalyst. This method is commonly employed in undergraduate teaching labs.

Formulations containing high concentrations of aspirin often smell like vinegar because aspirin can decompose through hydrolysis in moist conditions, yielding salicylic and acetic acids.

The acid dissociation constant ( pKa) for acetylsalicylic acid is 3.5 at 25°.

Polymorphism

Polymorphism, or the ability of a substance to form more than one crystal structure, is important in the development of pharmaceutical ingredients. Many drugs are receiving regulatory approval for only a single crystal form or polymorph. For a long time, only one crystal structure for aspirin was known. That aspirin might have a second crystalline form was suspected since the 1960s. The elusive second polymorph was first discovered by Vishweshwar and coworkers in 2005, and fine structural details were given by Bond et al. A new crystal type was found after attempted cocrystallization of aspirin and levetiracetam from hot acetonitrile. The form II is only stable at 100°K and reverts to form I at ambient temperature. In the (unambiguous) form I, two salicylic molecules form centrosymmetric dimers through the acetyl groups with the (acidic) methyl proton to carbonyl hydrogen bonds, and in the newly claimed form II, each salicylic molecule forms the same hydrogen bonds with two neighboring molecules instead of one. With respect to the hydrogen bonds formed by the carboxylic acid groups, both polymorphs form identical dimer structures.

Mechanism of action

Discovery of the mechanism

In 1971, British pharmacologist John Robert Vane, then employed by the Royal College of Surgeons in London, showed aspirin suppressed the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes. For this discovery he was awarded the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, jointly with Sune K. Bergström and Bengt I. Samuelsson. In 1984 he was made a Knight Bachelor.

Suppression of prostaglandins and thromboxanes

Aspirin's ability to suppress the production of prostaglandins and thromboxanes is due to its irreversible inactivation of the cyclooxygenase (PTGS) enzyme required for prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis. Aspirin acts as an acetylating agent where an acetyl group is covalently attached to a serine residue in the active site of the PTGS enzyme. This makes aspirin different from other NSAIDs (such as diclofenac and ibuprofen), which are reversible inhibitors.

Low-dose, long-term aspirin use irreversibly blocks the formation of thromboxane A2 in platelets, producing an inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation. This antithrombotic property makes aspirin useful for reducing the incidence of heart attacks. 40 mg of aspirin a day is able to inhibit a large proportion of maximum thromboxane A2 release provoked acutely, with the prostaglandin I2 synthesis being little affected; however, higher doses of aspirin are required to attain further inhibition.

Prostaglandins, local hormones produced in the body, have diverse effects, including the transmission of pain information to the brain, modulation of the hypothalamic thermostat, and inflammation. Thromboxanes are responsible for the aggregation of platelets that form blood clots. Heart attacks are caused primarily by blood clots, and low doses of aspirin are seen as an effective medical intervention for acute myocardial infarction. An unwanted side effect of the effective anticlotting action of aspirin is that it may cause excessive bleeding.

COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition

There are at least two different types of cyclooxygenase: COX-1 and COX-2. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COX-1 and modifies the enzymatic activity of COX-2. COX-2 normally produces prostanoids, most of which are proinflammatory. Aspirin-modified PTGS2 produces lipoxins, most of which are anti-inflammatory. Newer NSAID drugs, COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs), have been developed to inhibit only PTGS2, with the intent to reduce the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects.

However, several of the new COX-2 inhibitors, such as rofecoxib (Vioxx), have been withdrawn recently, after evidence emerged that PTGS2 inhibitors increase the risk of heart attack and stroke. Endothelial cells lining the microvasculature in the body are proposed to express PTGS2, and, by selectively inhibiting PTGS2, prostaglandin production (specifically, PGI2; prostacyclin) is downregulated with respect to thromboxane levels, as PTGS1 in platelets is unaffected. Thus, the protective anticoagulative effect of PGI2 is removed, increasing the risk of thrombus and associated heart attacks and other circulatory problems. Since platelets have no DNA, they are unable to synthesize new PTGS once aspirin has irreversibly inhibited the enzyme, an important difference with reversible inhibitors.

Additional mechanisms

Aspirin has been shown to have at least three additional modes of action. It uncouples oxidative phosphorylation in cartilaginous (and hepatic) mitochondria, by diffusing from the inner membrane space as a proton carrier back into the mitochondrial matrix, where it ionizes once again to release protons. In short, aspirin buffers and transports the protons. When high doses of aspirin are given, it may actually cause fever, owing to the heat released from the electron transport chain, as opposed to the antipyretic action of aspirin seen with lower doses. In addition, aspirin induces the formation of NO-radicals in the body, which have been shown in mice to have an independent mechanism of reducing inflammation. This reduced leukocyte adhesion, which is an important step in immune response to infection; however, there is currently insufficient evidence to show that aspirin helps to fight infection. More recent data also suggest salicylic acid and its derivatives modulate signaling through NF-κB. NF-κB, a transcription factor complex, plays a central role in many biological processes, including inflammation.

Aspirin is readily broken down in the body to salicylic acid, which itself has anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic effects. In 2012, salicylic acid was found to activate AMP-activated protein kinase, and this has been suggested as a possible explanation for some of the effects of both salicylic acid and aspirin. The acetyl portion of the aspirin molecule is not without its own targets. Acetylation of cellular proteins is a well-established phenomenon in the regulation of protein function at the posttranslational level. Recent studies have reported aspirin is able to acetylate several other targets in addition to COX isoenzymes. These acetylation reactions may explain many hitherto unexplained effects of aspirin.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity

Aspirin, like other medications affecting prostaglandin synthesis, has profound effects on the pituitary gland, which indirectly affects a number of other hormones and physiological functions. Effects on growth hormone, prolactin, and TSH (with relevant effect on T3 and T4) were observed directly. Aspirin reduces the effects of vasopressin and increases those of naloxone upon the secretion of ACTH and cortisol by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis), which has been suggested to occur through an interaction with endogenous prostaglandins and their role in regulating the HPA axis.

Pharmacokinetics

Salicylic acid is a weak acid, and very little of it is ionized in the stomach after oral administration. Acetylsalicylic acid is poorly soluble in the acidic conditions of the stomach, which can delay absorption of high doses for eight to 24 hours. The increased pH and larger surface area of the small intestine causes aspirin to be absorbed rapidly there, which in turn allows more of the salicylate to dissolve. Owing to the issue of solubility, however, aspirin is absorbed much more slowly during overdose, and plasma concentrations can continue to rise for up to 24 hours after ingestion.

About 50–80% of salicylate in the blood is bound to albumin protein, while the rest remains in the active, ionized state; protein binding is concentration-dependent. Saturation of binding sites leads to more free salicylate and increased toxicity. The volume of distribution is 0.1–0.2 l/kg. Acidosis increases the volume of distribution because of enhancement of tissue penetration of salicylates.

As much as 80% of therapeutic doses of salicylic acid is metabolized in the liver. Conjugation with glycine forms salicyluric acid, and with glucuronic acid it forms salicyl acyl and phenolic glucuronide. These metabolic pathways have only a limited capacity. Small amounts of salicylic acid are also hydroxylated to gentisic acid. With large salicylate doses, the kinetics switch from first order to zero order, as metabolic pathways become saturated and renal excretion becomes increasingly important.

Salicylates are excreted mainly by the kidneys as salicyluric acid (75%), free salicylic acid (10%), salicylic phenol (10%), and acyl glucuronides (5%), gentisic acid (< 1%), and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid. When small doses (less than 250 mg in an adult) are ingested, all pathways proceed by first-order kinetics, with an elimination half-life of about 2.0 to 4.5 hours. When higher doses of salicylate are ingested (more than 4 g), the half-life becomes much longer (15–30 hours), because the biotransformation pathways concerned with the formation of salicyluric acid and salicyl phenolic glucuronide become saturated. Renal excretion of salicylic acid becomes increasingly important as the metabolic pathways become saturated, because it is extremely sensitive to changes in urinary pH. A 10- to 20-fold increase in renal clearance occurs when urine pH is increased from 5 to 8. The use of urinary alkalinization exploits this particular aspect of salicylate elimination.

History

Plant extracts, including willow bark and spiraea, of which salicylic acid was the active ingredient, had been known to help alleviate headaches, pains, and fevers since antiquity. The father of modern medicine, Hippocrates, who lived sometime between 460 BC and 377 BC, left historical records describing the use of powder made from the bark and leaves of the willow tree to help these symptoms.

A French chemist, Charles Frederic Gerhardt, was the first to prepare acetylsalicylic acid in 1853. In the course of his work on the synthesis and properties of various acid anhydrides, he mixed acetyl chloride with a sodium salt of salicylic acid ( sodium salicylate). A vigorous reaction ensued, and the resulting melt soon solidified. Since no structural theory existed at that time, Gerhardt called the compound he obtained "salicylic-acetic anhydride" (wasserfreie Salicylsäure-Essigsäure). This preparation of aspirin ("salicylic-acetic anhydride") was one of the many reactions Gerhardt conducted for his paper on anhydrides and he did not pursue it further.

Six years later, in 1859, von Gilm obtained analytically pure acetylsalicylic acid (which he called acetylierte Salicylsäure, acetylated salicylic acid) by a reaction of salicylic acid and acetyl chloride. In 1869, Schröder, Prinzhorn and Kraut repeated both Gerhardt's (from sodium salicylate) and von Gilm's (from salicylic acid) syntheses and concluded both reactions gave the same compound—acetylsalicylic acid. They were first to assign to it the correct structure with the acetyl group connected to the phenolic oxygen.

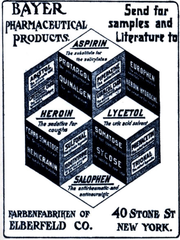

In 1897, chemists working at Bayer AG produced a synthetically altered version of salicin, derived from the species Filipendula ulmaria (meadowsweet), which caused less digestive upset than pure salicylic acid. The identity of the lead chemist on this project is a matter of controversy. Bayer states the work was done by Felix Hoffmann, but the Jewish chemist Arthur Eichengrün later claimed he was the lead investigator and records of his contribution were expunged under the Nazi regime. The new drug, formally acetylsalicylic acid, was named Aspirin by Bayer AG after the old botanical name for meadowsweet, Spiraea ulmaria. By 1899, Bayer was selling it around the world. The name Aspirin is derived from "acetyl" and Spirsäure, an old German name for salicylic acid. The popularity of aspirin grew over the first half of the 20th century, spurred by its supposed effectiveness in the wake of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. However, recent research suggests the high death toll of the 1918 flu was partly due to aspirin, as the doses used at times can lead to toxicity, fluid in the lungs, and, in some cases, contribute to secondary bacterial infections and mortality. Aspirin's profitability led to fierce competition and the proliferation of aspirin brands and products, especially after the American patent held by Bayer expired in 1917.

The popularity of aspirin declined after the market releases of paracetamol (acetaminophen) in 1956 and ibuprofen in 1969. In the 1960s and 1970s, John Vane and others discovered the basic mechanism of aspirin's effects, while clinical trials and other studies from the 1960s to the 1980s established aspirin's efficacy as an anticlotting agent that reduces the risk of clotting diseases. Aspirin sales revived considerably in the last decades of the 20th century, and remain strong in the 21st century, because of its widespread use as a preventive treatment for heart attacks and strokes.

Trademark

As part of war reparations specified in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles following Germany's surrender after World War I, Aspirin (along with heroin) lost its status as a registered trademark in France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where it became a generic name. Today, aspirin is a generic word in Australia, France, India, Ireland, New Zealand, Pakistan, Jamaica, Colombia, the Philippines, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. Aspirin, with a capital "A", remains a registered trademark of Bayer in Germany, Canada, Mexico, and in over 80 other countries, where the trademark is owned by Bayer, using acetylsalicylic acid in all markets, but using different packaging and physical aspects for each.

Compendial status

- United States Pharmacopeia

- British Pharmacopoeia

Veterinary use

Aspirin is sometimes used for pain relief or as an anticoagulant in veterinary medicine, primarily in dogs and sometimes horses, although newer medications with fewer side effects are generally used, instead. Both dogs and horses are susceptible to the gastrointestinal side effects associated with salicylates, but it is a convenient treatment for arthritis in older dogs, and has shown some promise in cases of laminitis in horses. Aspirin should be used in animals only under the direct supervision of a veterinarian; in particular, cats lack the glucuronide conjugates that aid in the excretion of aspirin, making even low doses potentially toxic.